Statistics South Africa faces an existential threat called “Covid-19”, but really the threat is older and deeper. Here are some practical examples of why we need Stats SA to survive the Command Council.

Stats SA was once one of the country’s world-class public institutions, the “fact-finder of the nation”, but no more. According to Dr Pali Lehohla, former Statistician-General, StatsSA has been reduced to “the blind that should lead the lame”.

In part that is because of the recent decision not to run the Income and Expenditure Survey and the Living Conditions Survey this year. But the problems run deeper.

According to Professor David Everatt, chairperson of the Stats SA council, in February this year one in every five posts at Stats SA lay vacant as a result of a freeze on appointments and promotions. Everatt said that if this continued “Council will withdraw our support for official statistics, and resign.”

After that Treasury, under Tito Mboweni, promised to fill the funding gap, with allocations supposed to come into effect on 1 April. Since lockdown disrupted almost everything in March it is not clear whether these promises took effect, but Lehohla’s plea strongly suggests not.

Nor would this be the first time that promises around Stats SA were broken. According to Treasury’s proposed budget summary, R70 million was to be set aside in 2018/2019 “to conduct an income and expenditure survey as part of the household surveys programme to gain a better understanding of wealth inequalities in South Africa”.

However, when Stats SA released its November 2019 report, Inequality Trends in South Africa: A multidimensional diagnostic of inequality,the most recent income and expenditure data were from the latest such survey, in 2015. Whatever happened to the proposed 2018/2019 research?

The 2019 report, based mostly on data going up to 2015, was hailed in the Mail & Guardian and the Daily Maverick as the “first of its kind”, and was covered in every major outlet in the country with headlines like this one from TimesLive: “Whites earn three times more than blacks: Stats SA”.

Findings were obscured

This generated talking points that dominated radio and television punditry for weeks, largely hailed as proving “what everyone already knows” about “racialized inequality”. For all the coverage, arguably the Report’s most surprising findings were obscured.

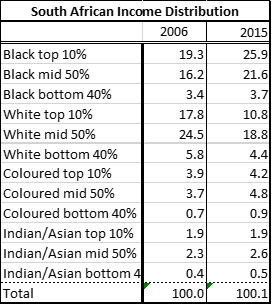

According to the report, by 2015 black South Africans were earning 51.1% of all income, compared to 34.1% for white South Africans, a fact hardly repeated. This had shifted from 39% (black) and (48.2%) white in 2006.

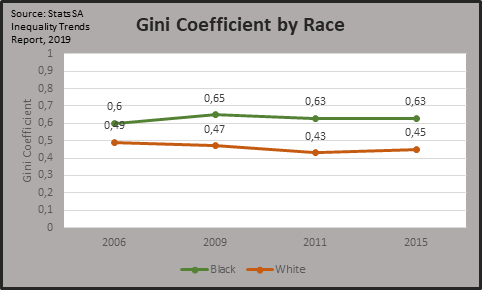

The report further noted that 53.9% of all income was earned by the top 10% across races. The report drew attention to the fact that income inequality within races was highest among black people and lowest among white people, which seriously undermines the thought that BEE has worked for most black people. This can be seen by looking at the Gini Coefficient, a measure of inequality where the higher the value is the higher the inequality is.

So the largest intra-racial income inequality is amongst black people, but how much income does the black elite earn as a national portion? Unfortunately the report never combined data on inter-racial distributions with intra-racial distributions to compare, for example, the income of the black richest 10% with its white equivalent.

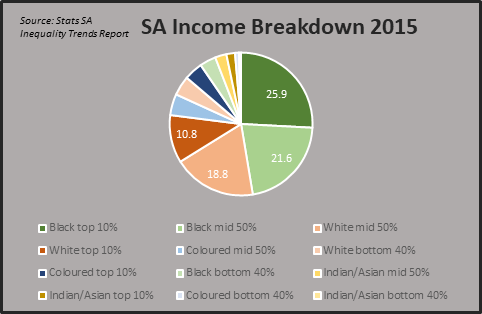

If one does this the following picture emerges.

As you can see from the pie-chart above the highest earning black 10% gets the largest slice of income in the country, 2.5 times bigger than the highest earning white 10%. The white top 10% is only the fourth largest earner by race-class category — the biggest being the black 10%; then the middle 50% of black earners; then the middle 50% of white earners; and only then the white elite.

Think again

Why does this matter? Well if in 2020 you still thought that the economy was run by “white monopoly capital”, this might make you think again.

If you were the Transport Minister, Fikile Mbalula, who said in 2017 it was a “fact” that “80% of our tax revenue” comes from “whites, this is a monopoly itself”, then the data above might make you think again.

If you thought, as the most powerful minister in the country still does, that “class suicide” might be a good idea (on the implicit assumption that destroying the top two income tiers would mean spiting the white) then this official data from 2015 might make you think again too.

If you thought, as the Chief Director of Labour Relations, Thembinkosi Mkhaliphi, does, that “over the last 21 years nothing has happened that should have happened and no real change has taken place” so that BEE regulations must be tightened to secure a new black managerial elite among the “middle-to-upper occupational levels” then this data might open your eyes to what has already been done.

And finally if you thought, as the President of the Republic does, that possibly the world’s most brutal, irrational, and arbitrary lockdown has delivered necessary blows to markets and industry which needed to fall because they operated in a “racist and colonial” economy, then the demonstrated fact that black people were already earning the lion’s share of income since 2015 might give you pause for serious reconsideration.

Sadly, the overlooked data also show that by 2015 the balancing of inter-racial income inequalities was not coming about in a productive way.

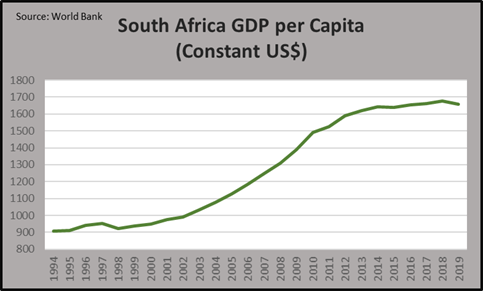

What should have happened is this. The overall share of incomes going to non-white South Africans should have increased via growth across all races, but with the highest rate of growth among exactly the non-white people who started off from artificially (and brutally) repressed positions. This is exactly what did happen in the Mandela-Mbeki era.

But since then white median household incomes dropped from roughly R140 000 in 2011 to R120 000 in 2015, while Indian incomes dropped by a similar proportion, almost 20%, in the same period, and coloured incomes stayed flat.

It is hard to find anything like the median income decline over four years in constitutional democracies anywhere else on the planet.

Not good enough

Only black median household incomes grew significantly at this time, around 10% from a low base of R9 800 to R10 800. Not good enough.

The “boiling frogs” strategy not of overall growth, but of slowly draining wealth from some race groups to another amid general contraction is economically unsustainable, politically inconsistent with our constitutional values, and inhumane.

This “boiling frogs” strategy has also been detrimental to the poorest 40% of black South Africans whose share of black income declined from 2006 to 2015 by nearly 20% (18.18%) and whose share of national income stayed flat.

No one could know that this is exactly what happened if it were not for Stats SA. Unfortunately, you cannot know exactly what has happened since 2015 (and neither can I) because no new data of this kind have been made available by the understaffed national factfinder.

Esoteric ‘asset scores’

Worse, no genuine wealth inequality data by race have been made available even in the “first of its kind” report, since it only provided esoteric “asset scores” rather than proper data to reckon with.

This reminds me of New World Wealth, a private consultancy which found that among South Africa’s 1%, aka high net worth individuals, aka dollar millionaires, black people in the broader definition were overtaking white people in 2015. New World Wealth continued publishing research about the 1% in the years since, but never again broke its data down by race.

In a country whose taste-making elite are obsessed with promoting “black excellence” there is something shocking about the lacuna of data about black dollar millionaires and top income earners. Race laws remain front and centre of the ANC-EFF coalition’s agenda; by one calculation there are tens of thousands in effect already, so facts about inter- and intra-racial income and wealth distributions must be brought to political debate.

We cannot rely on the private sector to generate all the relevant research. We need Stats SA to do the old-fashioned job of holding up a mirror to this republic that puts facts before mythological narrative. Instead of directing a few score million to that effort, a project in which every South African has a vested interest, over R10 billion has been pledged to SAA despite repeated promises this would not happen. Vanity beats truth once more. The “blind leading the lame” indeed.

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend

Image by Paolo Trabattoni from Pixabay