This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

18th July 1994 – Rwandan genocide: The Rwandan Patriotic Front takes control of Gisenyi and north western Rwanda, forcing the interim government into Zaire and ending the genocide

In 1990, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). a group consisting of refugees who were mostly of Rwanda’s main ethnic minority, the Tutsis, invaded Rwanda from their base in Uganda. The fighting between the RPF and the Rwandan government, which was dominated by the Hutu ethnic group, was inconclusive and a peace agreement was signed in 1993.

However, when, on 6 April 1994, a plane carrying the Hutu presidents of Rwanda and Burundi was shot down by an anti-aircraft missile as it came in to land at Rwanda’s main airport, the peace treaty collapsed, setting off a wave of genocidal killings, with soldiers, militiamen and police killing Tutsi and moderate Hutu politicians and soldiers.

The violence intensified over the next few months, with Hutu troops and militias carrying out massive attacks on the civilian population. Genocidal militias roved the country hunting down, raping and slaughtering any Tutsis, or Hutus who were not participating in the genocide. Most of the attacks were carried out by gangs using machetes and rifles.

The RPF for its part restarted the civil war and began attacks on government positions across the country.

The United Nations, despite having a presence in the area, was prevented from intervening in the conflict and there was no major outside intervention by any power to stop the genocide.

On 18 July, the RPF managed to drive the last of the Hutu extremists of the old government into exile in neighbouring Zaire (modern day Democratic Republic of Congo), bringing an end to the genocide.

In the final count, the genocide claimed between 500 000 and 1 000 000 lives – some 70% of the country’s Tutsi population – and left an estimated 250 000 to 500 000 women raped by troops or militias. The rate of killing rivalled the Holocaust in Europe for its scale and speed. Around 30% of the country’s Twa (pygmy) population was also slaughtered in the genocide.

While ethnic tensions had existed in Rwanda for generations, the genocidal movement of 1994 had its origins in the ‘Hutu Power’ movement, which became a major political force in the government around the time of the 1990 invasion by the RPF.

The Hutu Power movement founded anti-Tutsi magazines and radio stations to radicalise the population against Tutsis, and had a special focus on Hutus who married Tutsis, whom the Hutu Power movement called traitors. By the start of the genocide, the Hutu Power movement had become so widespread that no political movement in the country was without a Hutu Power faction.

During the 1990-1993 war, Hutu Power groups carried out small-scale killings of Tutsis, claiming that they were simply fighting the RPF. During the civil war, the Rwandan government began arming and training Hutu men across the country and forming militias. In 1993, the Hutu Power groups began to import huge numbers of machetes into the country and began drawing up lists of ‘traitors’ whom they wished to exterminate. Hutu Power radio stations began referring to Tutsis as cockroaches who needed to be wiped out.

The identity of the perpetrators of the assassination that sparked the genocide is still disputed by historians. While the RPF may have been responsible, the speed at which the genocide began suggests that the Hutu Power movement may have carried out the assassination as a way to reignite the civil war and allow them to carry out the genocide which they may have been planning for a year.

The genocide had profound consequences; the Tutsi-dominated RPF led by Paul Kagame took control of Rwanda, after forcing out the Hutu Power groups, and instituted a strict authoritarian regime. Kagame rules almost unchecked and speech is tightly controlled in the name of uprooting ‘genocide propaganda’.

The Hutu Power movement was pursued into Zaire by the RPF after it sought shelter from the government of Zaire. This started a series of wars across the region, which would claim the lives of a further 6 million people. These conflicts in the Congo, sometimes referred to as Africa’s world war, finally ended in 2003 when a peace treaty was signed in Pretoria.

The events of the genocide are harrowingly depicted in the film Hotel Rwanda.

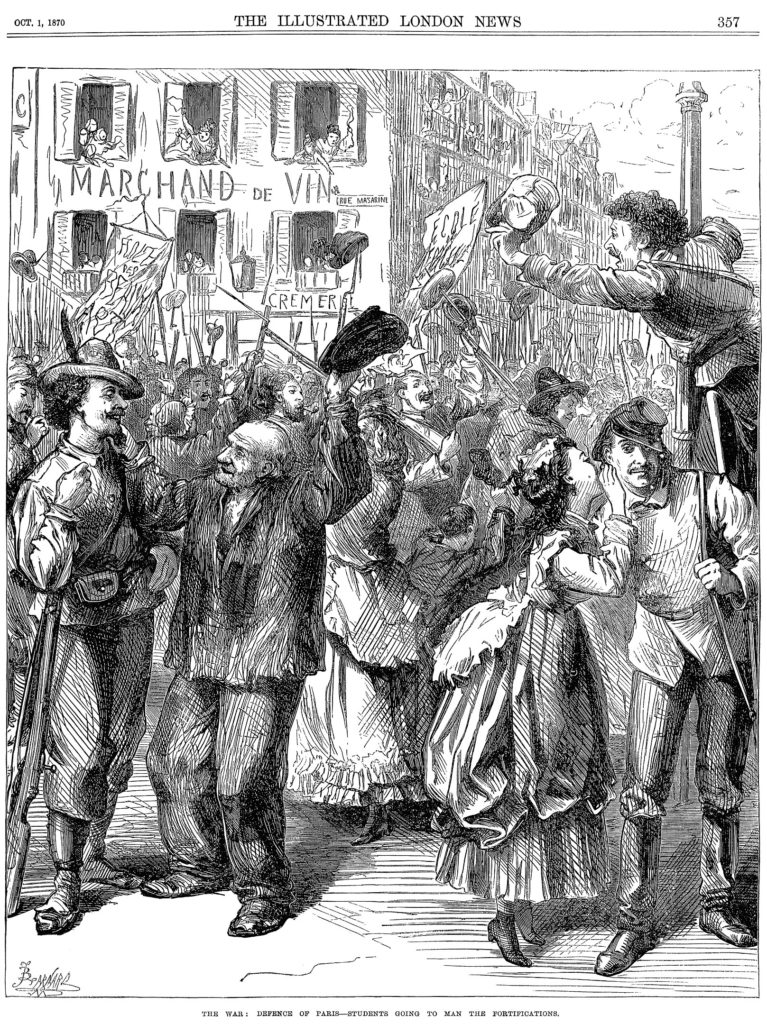

19th July 1870 – Franco-Prussian War: France declares war on Prussia

The ultimate cause of the Franco-Prussian war was the growing power of the Kingdom of Prussia and the French fear that a united Germany would lead to French defeat and subservience to Germany.

Officially, the war was between the ‘North German Confederation’ and its allies, the three remaining independent German states which were not part of the Confederation, and the Second French Empire, which later became the Third French Republic.

The Germans, led by the chancellor of Prussia, Otto Von Bismark, realised that a war with all the German states on one side would provide a great opportunity for Germany to unify, and to demonstrate its strength on the world stage. To that effect, many historians believe that Bismark intentionally provoked the French, using an altered telegram which was deliberately leaked to the French to make it seem that the French envoy had been mistreated by the Germans.

On 19 July, France declared war on the North German Confederation. However, its forces were quickly overwhelmed by the German armies, which had mobilised more men with the clever use of railways. The well-led, larger and better-equipped German army invaded northern France and captured the French emperor, Napoleon III, a defeat that sent the French reeling and saw the remaining government of France declare itself the Third French Republic.

By January, Paris was under siege by German forces, with the city falling by the end of the month. In the chaos that followed, a revolutionary commune, called the Paris Commune, rose up and took over the capital. The commune would eventually be crushed by the French army in May 1871.

Victory in the war saw the North German Confederation annex two of the eastern provinces of France, Alsace and Lorraine, and led to the declaration of the German Empire, which saw the incorporation of all the German states, except Austria and Lichtenstein, forming the first predecessor of the Federal Republic Germany that exists today.

France would also have to pay enormous reparations to Germany, with the aftermath of the hostilities breaking the balance of power which had existed in Europe since the defeat of Napoleon in 1815.

With that balance broken, the stage was set for the war which would destroy forever Europe as it was known: the First World War.

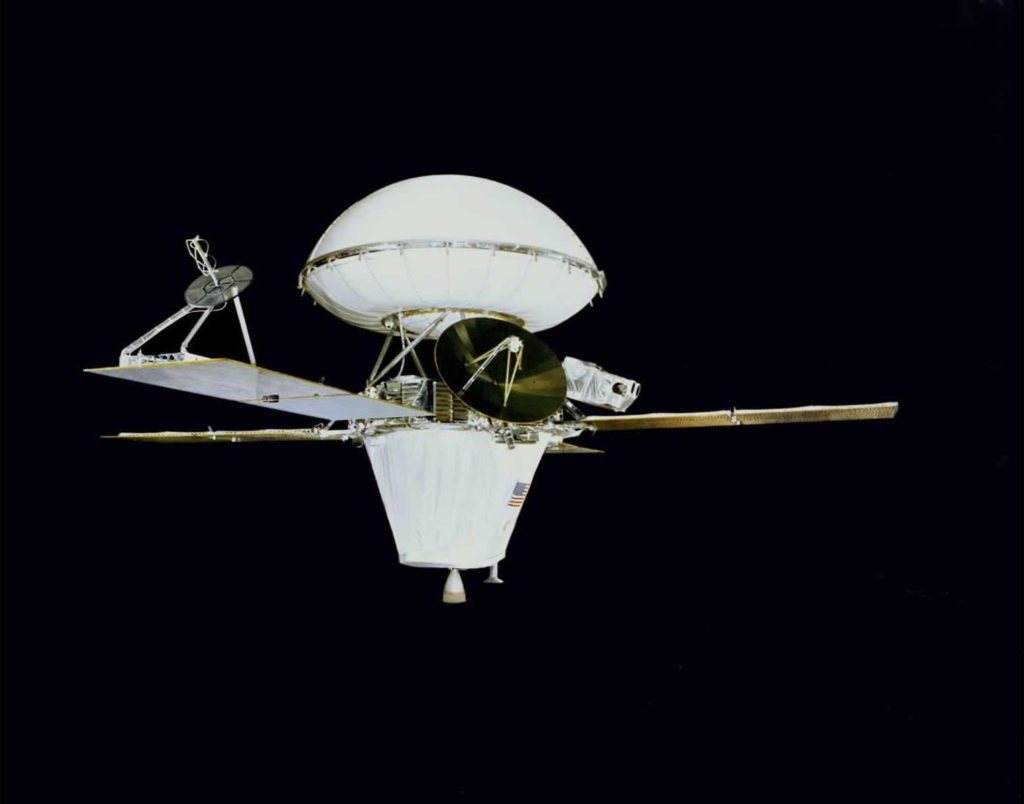

20th July 1976 – The American Viking 1 lander successfully lands on Mars

The Viking 1 lander was the first probe sent to be Mars that managed to successfully complete its mission, and the second to make a soft landing on the surface. (A Soviet probe had landed on Mars five years earlier, though ceased working after 15 seconds). On 20 July 1976, after an 11-month journey to Mars, Viking 1 touched down on Chryse Planitia (Greek for ‘Golden Plain’), the smooth circular plain in the northern equatorial region of Mars.

As part of America’s efforts to map the solar system and demonstrate its technological supremacy over the Soviets, the Viking programme sent back the first pictures of the Martian surface, and performed the first experiment intended to establish if there was life on Mars. The experiment to find life produced mixed results; while the majority of scientists believe that the positive readings were a false positive, some believe that this first test showed that life does in fact exist on Mars.

The Viking 1 lander was a breakthrough in the exploration of Mars and has left a legacy of many successful missions in its wake.

Perhaps future Martian colonists will remember the Viking 1 as the first step of their civilization.

21st July 1645 – Qing dynasty regent Dorgon issues an edict ordering all Han Chinese men to shave their foreheads and braid the rest of their hair into a ‘queue’ identical to those of the Manchus

After the Manchu peoples of what is today north-eastern China invaded and conquered the Ming dynasty in 1644, the new regent, Dorgon, issued an order known as the Queue Order, which decreed that all Han Chinese (Han Chinese are China’s largest ethnic group) males should shave their foreheads and braid their hair into a long strand at the back, a hairstyle called a queue. Any man who refused to comply would be killed.

This order was part of establishing the dominance of the new regime over China. The Ming dynasty, which had just been destroyed, was a majority Han Chinese government that had arisen from popular Han Chinese rebellions against the Mongol emperors of the Yuan dynasty which had ruled China after the conquests of Genghis Khan. As such, the Ming dynasty’s identity and legitimacy was tied up in Han Chinese identity and rebellion against foreign rule. The new Qing dynasty, which had just conquered China, drew its strength from the Manchu people, a group of horse nomads, who, like the Mongols before them, had invaded from China’s north.

The Manchu, being vastly smaller in number than their new Han subjects, and fearful of a Han rebellion, sought to enforce a kind of cultural hegemony over their subjects by promoting and enforcing Manchu rites and customs. And, likewise, if officials continued to promote the cultural practices of the Ming, (such as men growing their hair long at the front) then they would be subject to suspicion. As the Qing leader said: ‘If officials say that people should not respect our Rites and Music, but rather follow those of the Ming, what can be their true intentions?’

The Qing also reasoned that the rules of Confucian thought taught that an emperor and his subjects were like father and son, and, thus, since the emperor wore his hair in a queue, his subjects should respect their father and shave their heads in the same way.

The Manchu queue would remain a common feature of Chinese dress and custom until the 20th century.

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend