Covid-19 is spreading in South Africa at an exponential rate. Because this does not suit the official narrative, or our common interest in lifting the alcohol and cigarette ban, information given about the rate of spread has been deliberately confusing. But here are the facts.

Last week Health Minister Zweli Mkhize described a ‘plateau we are observing’ in newly confirmed Covid-19 cases. This claim has been widely repeated, prompting hope that lockdown will finally be lifted.

South Africans overwhelmingly want the lockdown to end, so many are eager to believe any potential good news about passing the peak that might cause the National Coronavirus Command Council (NCCC) to rethink its ‘irrational’ regulations.

But wishful thinking should not trick South Africans into believing the spread of Covid-19 is slowing. The ‘plateau’ is an illusion.

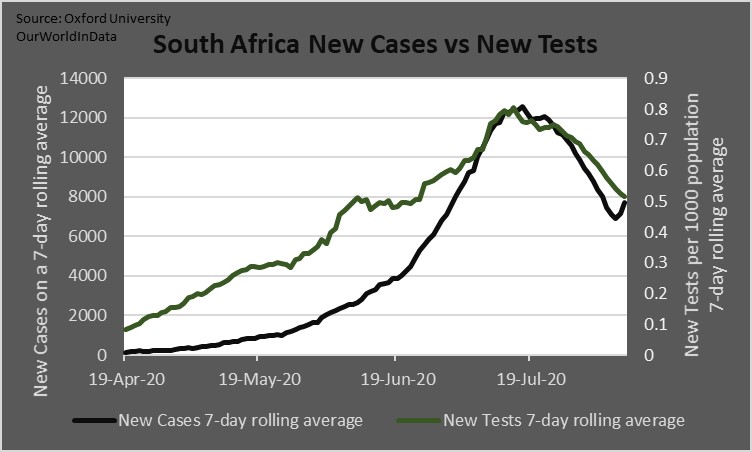

The dip in new cases since 19 July matches all too neatly a dip in new tests since the same date. Unfortunately, this fact drastically undermines any claim that the spread is slowing in South Africa.

As United States President Donald Trump said, ‘with smaller testing we would show fewer cases‘. Someone in the NCCC seems to have been listening.

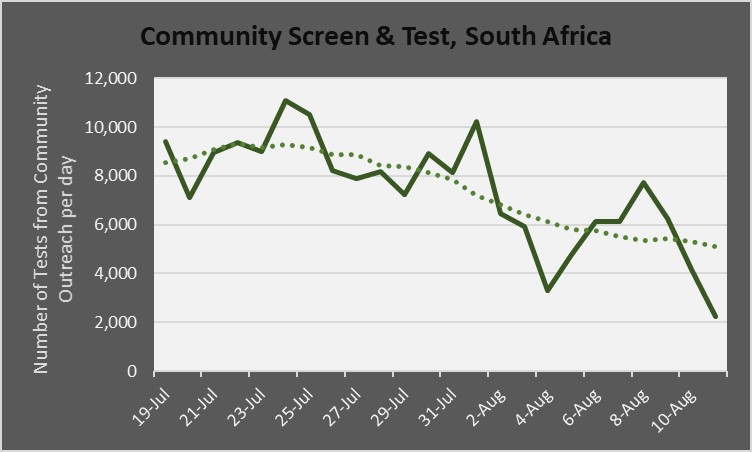

The National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) indicates whether tests were ‘passive’, basically meaning sick people go to get tested, or whether they are the consequence of ‘community screening’, where cases are actively sought in the wider population.

In the graph above, you can see that from a peak of 11 000 community outreach tests per day on 24 July, the number dropped to just over 2 000 on Tuesday 11 August.

Less active testing produces fewer confirmed cases, creating the impression of a ‘plateau’. But halting community testing does not mean the NCCC halted the community spread of Covid-19.

Some of the most dramatic reductions in testing have occurred in Gauteng, a province where Dr Mkhize suggested that the numbers infected may have peaked already. According to NICD data, in the first full week of July 500 tests were done in Gauteng per 100 000 of the population, which came down to 340 tests per 100 000 by the end of July, after which there is no reliable data.

So the sharpest decline in provincial testing coincided with a relative decline in new cases. Again this is not a ‘good news’ reason to suppose Gauteng has peaked.

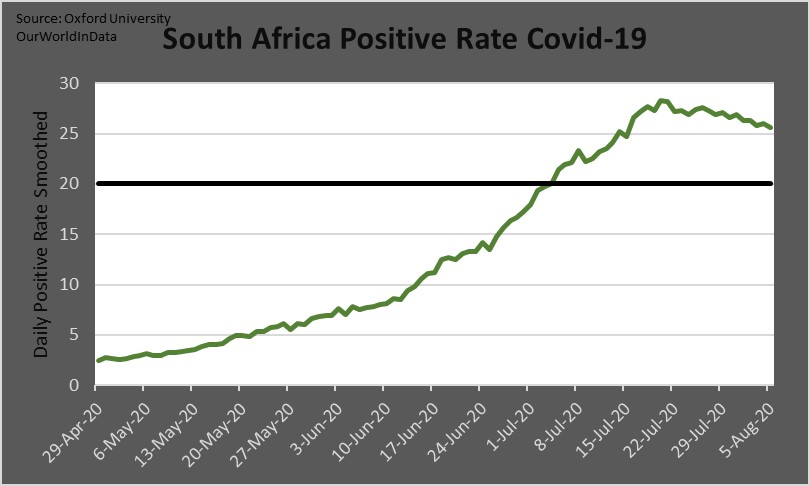

The positive rate measures the portion of tests conducted that come out positive. In Gauteng, this climbed from 24% in late June to 31% in late July.

In the above graph, you can see the positive rate of tests nationally. In April, this was around 2.5%, climbing to around 7% in May. By 4 July, the positive rate climbed above 20%, and by 14 July it soared past the 25% mark, around which it has remained ever since. That means one in every four tests conducted comes out positive.

As Razina Munshi observed in Business Day, a high positive rate ‘may mean a country is only testing its sickest patients, who seek medical attention, and isn’t casting a wide enough net to know how much of the virus is spreading within its communities’.

According to the World Health Organisation’s original stance, a positive rate of 5% is the acceptable ceiling for viable analysis of viral community spread, but it has since broadened this to ‘a positive rate of around 3-12% as a general benchmark for adequate testing’.

At more than double the 12% benchmark positive rate, our testing is simply too inadequate to give substantial meaning to the ‘plateau’ in new cases. But that is not where the problems with Dr Mkhize’s ‘observed plateau’ end.

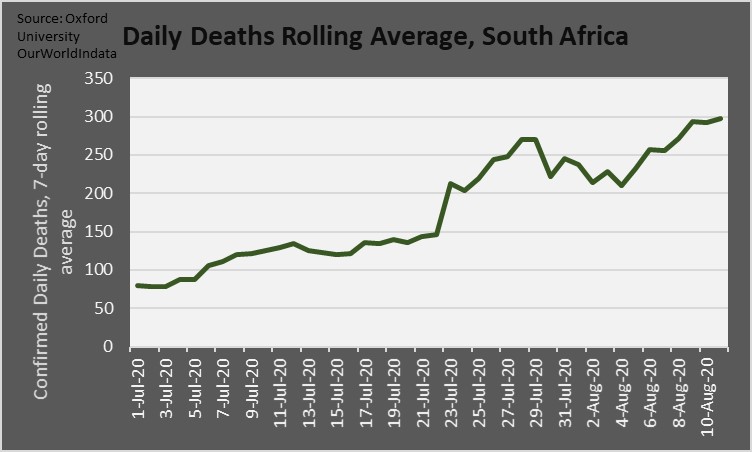

The national rate of death further indicates that the virus continues to spread aggressively.

The final point to consider is that the Western Cape really has been shown to have peaked, on all the measures so far considered, including testing rates, case rates, positive rates and death rates.

Because the Western Cape really has peaked, if the national averages started to ‘plateau’ that would be consistent with exponential spread continuing elsewhere, with the Western Cape dip cancelling out the national incline to some extent.

Everyone wants to believe that Covid-19 has peaked nationally, but the data do not back that wish up.

We should not have to pretend to believe the NCCC’s half-truths in order to call for lockdown to end. Lockdown must end, not because ‘it worked’, but precisely because it has not worked and continues to do more harm than good.

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend