This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

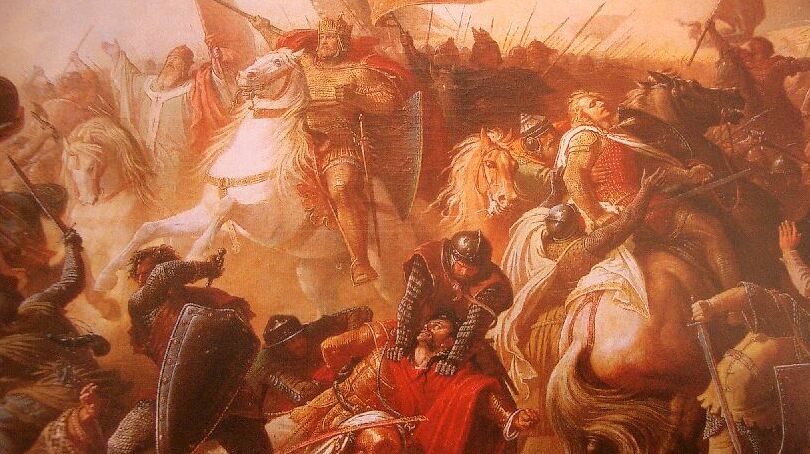

10th August 955 – Battle of Lechfeld: Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor defeats the Magyars, ending 50 years of Magyar invasion of the West

Hungary is not a country which occupies much space in the minds of many people outside central Europe. Most people’s knowledge of Hungary is confined to its president, Viktor Orban, some memory of the 1956 uprising against Soviet rule and perhaps a fond memory of a short trip there to see the capital Budapest.

There was a time, however, when the people of Hungary – the Magyar, as the Hungarians refer to themselves – were the terror of central Europe. They were fierce horse-riding nomads who raided Germany, Italy and the Balkans, bringing waves of terror and destruction with them. Christian monks would describe them as beasts and demons. While Viking raids brought dread to the coasts of Western Europe, those who fled inland to the east made themselves vulnerable to the ravages of the mighty Magyar warriors.

Set around the Ural mountains in what is today central Russia, the early history of the Magyar people is not well known or understood. All that is known for sure is that at some point in the 4th or 5th century the Magyar began migrating west towards modern-day Romania.

The Magyar lived on the open grasslands of the Eurasian steppe as nomads, herding sheep, cows and horses, but rarely grew crops. This was a hard lifestyle and it bred a tough and warlike people as used to fighting off wild animals as other mounted nomads. They were a pagan people, likely worshiping some variant of the sky god of the Steppe peoples, a deity called Tengri by modern scholars.

We first hear of the Magyar in the historical record in 811 when they supposedly were present in the Bulgarian army that fought the Eastern Roman Empire. At this time, they were likely living in western Ukraine on the eastern side of the Carpathian Mountains.

In 881, there began the raiding for loot and slaves deep into Europe, into Germany and the territory that is the modern-day Czech Republic. Around the end of the 9th century, fleeing from another horse nomad group, the Pechenegs, the Hungarians crossed the Carpathian Mountains and defeated the tribes inhabiting the Pannonian plain, which is today modern-day Hungary. Here, the Magyar settled and began raiding all their neighbours to the west and south. In 901 they raided Italy, and by 915 their raids reached as far as Bremen on the northern German coastline. In 926, the Magyar army ravaged south-west Germany and Luxembourg, and in 937 they raided France. By 955, historians believe they had carried out around 47 major raids across Europe, only eight of which had failed.

As the middle of the 10th century approached, the Magyar faced a new threat in the form of the powerful new German king, Otto I.

Otto had greatly strengthened Germany since coming to the throne in 936. In 955, seeking to exploit some rebellions against Otto, the Magyar army invaded Bavaria in southern Germany and sought to draw the German army out to face them.

Otto obliged and hastily marched what troops he could to save Bavaria. On 9 August, the two armies confronted each other on the plain of Lechfeld. In several engagements over the next three days the Germans annihilated almost the entire Magyar army. All of the captured Magyars were either killed or mutilated, having their noses and ears cut off by the Germans.

The defeat of the Magyars at Lechfeld would signal the end of their raids into western Europe and catapult Otto into legendary fame. Within less than 50 years, the Magyar people would convert to Catholicism and their leader would be crowned by the Pope as the first King of Hungary.

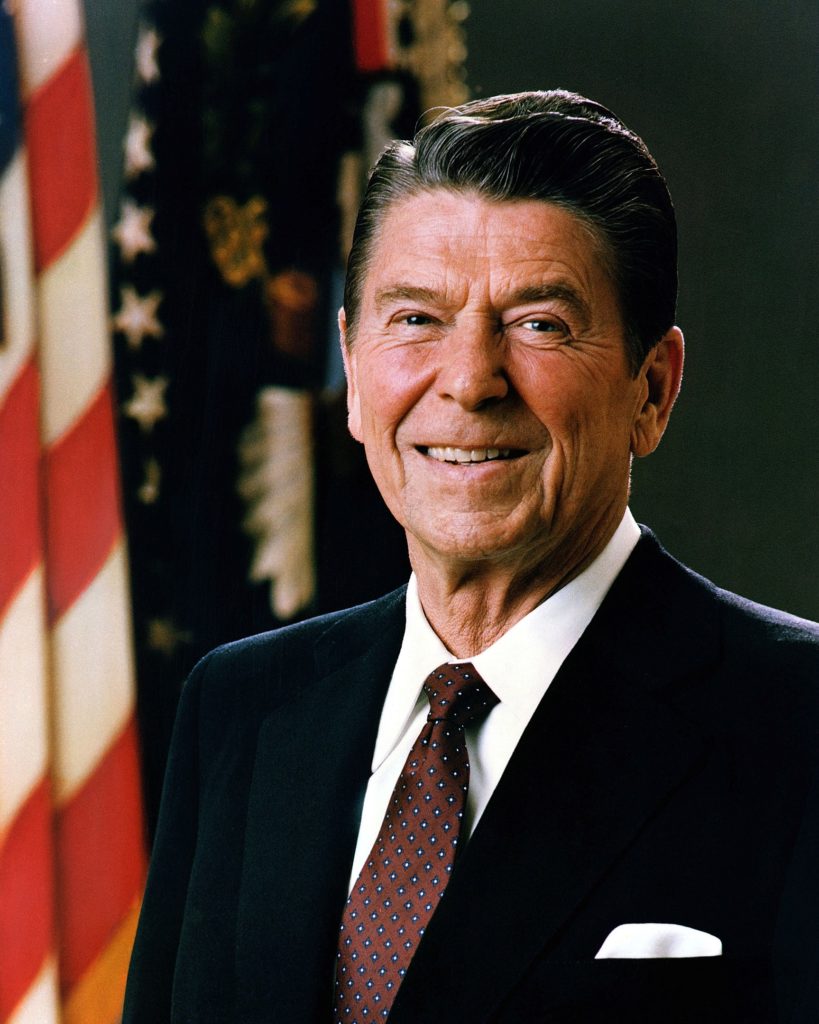

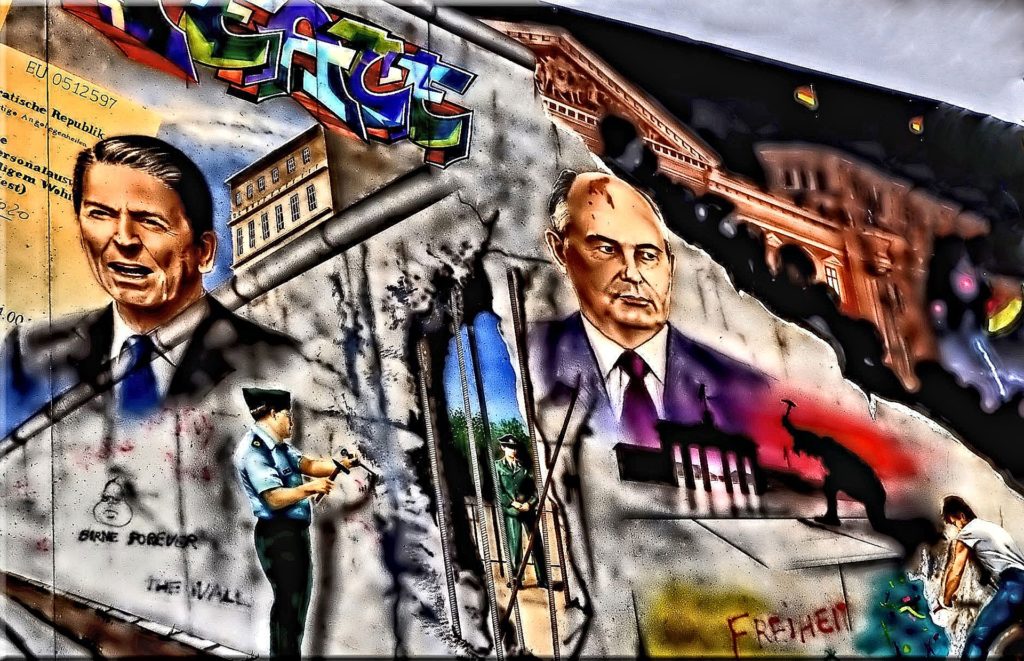

11th August 1984 – ‘We begin bombing in five minutes’: United States President Ronald Reagan

On the morning of 11 August, American president Ronald Reagan settled in to record a broadcast on National Public Radio announcing his signing of the Equal Access Act into law, one of the signature pieces of legislation of his re-election campaign. It was around three months to the election and the law’s promotion was important to ensure he maintained support among Christian conservatives.

Reagan did the recording at his holiday home in Santa Barbara in California, where a studio had been set up for the broadcast. In the minutes before going live, the radio engineers required him to perform sound checks.

Many radio stations which were intending to carry the broadcast had already tuned in to the audio feed and were recording the sound check, too.

Characteristically, Reagan was cracking jokes with the sound engineers as they did their tests, and, while pretending to read the speech he had prepared on the Equal Access law, he quipped: ‘My fellow Americans, I’m pleased to tell you today that I’ve signed legislation that will outlaw Russia forever. We begin bombing in five minutes.’

This was transmitted to many radio stations already tuned in and recording, and within days was leaked to the public.

When Reagan’s joke reached the Soviet Union, it briefly set off a panic and American intelligence intercepted a message suggesting the Soviets might be preparing to attack. However, with no troop movements detected, the tension quickly cooled.

The Soviet government did not respond, but Pravda, the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, furiously denounced the joke as ‘unprecedentedly hostile’ and demonstrative of the insincerity of America’s commitment to improving relations between the two countries.

Reagan’s opponent in the 1984 election, Walter Mondale, who had been trailing in the polls, believed briefly that this mistake might allow him to close the polling gap, as Reagan’s support took a hit in the days after the remark was revealed. Mondale attacked Reagan, saying: ‘A President has to be very, very careful with his words.’

The attacks soon backfired, however, with Reagan succeeding in casting himself as cool, calm, and collected, while Mondale seemed oversensitive.

The joke endured in the minds of many as a particularly memorable moment of the Reagan presidency, and references to it can still often be found in pop culture today.

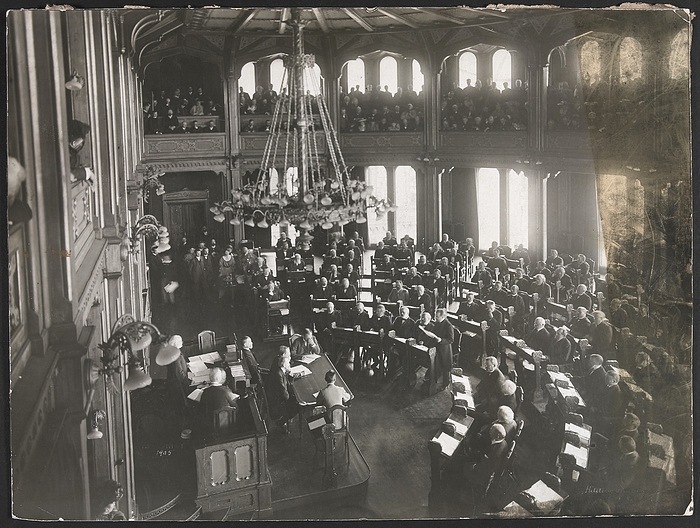

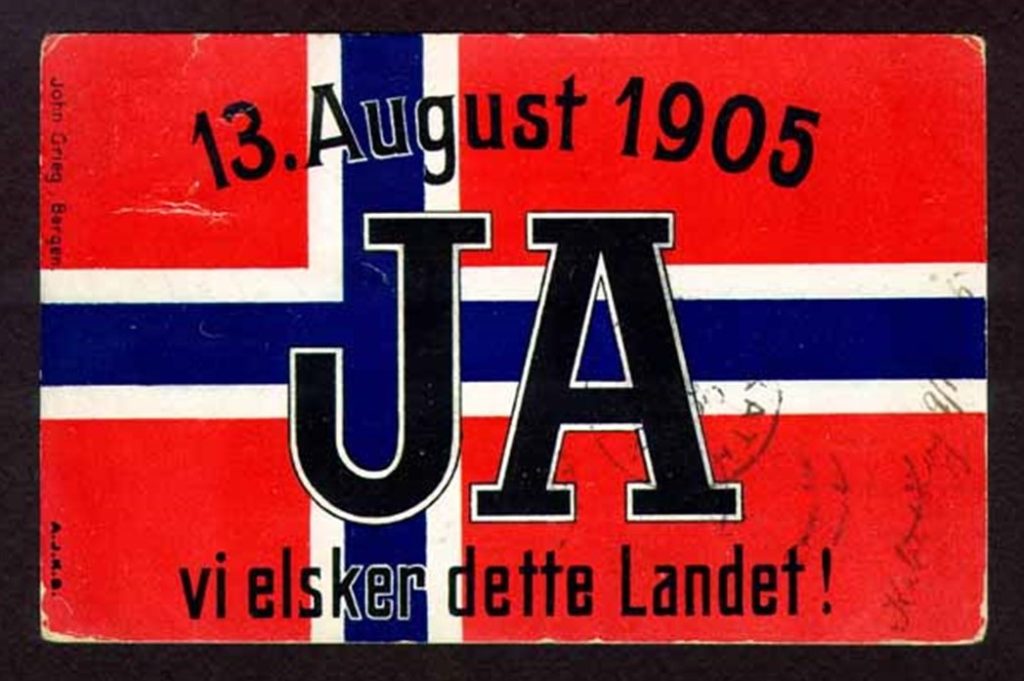

13th August 1905 – Norwegians vote to end the union with Sweden

Sweden, Norway and Denmark, the three Scandinavian countries, have had a long shared history, occasionally as allies and often as enemies.

Between 1397 and 1523, the three kingdoms had been united under a single king in a ‘Personal Union’; each kingdom remained distinct, with its own laws, armies and customs, but all three shared a united foreign policy and a single king. This is usually referred to as the Union of Kalmar.

In 1523, the Swedes rebelled against the Union, which was dominated by Denmark, and broke free. In the aftermath, Norway remained under the control of the Danish King and would remain so for the next three centuries until 1814.

During the Napoleonic wars, Denmark sided with France and suffered many defeats at the hands of the British navy as a result. In 1814, facing an invasion by Russia, Prussia and Sweden and a naval blockade by Britain, the Danes surrendered and transferred Norway from their control to a personal union with Sweden.

During this transfer, there was a brief attempt by the Norwegians to become independent, but this was crushed by the Swedish army.

The Norwegian Constitution remained more democratic than the Swedish one, and so, while they were now ruled by a Swedish king, the Norwegians retained their constitutional structure which greatly diminished the power of the Swedish king.

The growing democratisation of the Norwegian system would increasingly drive them apart from the Swedes, who were slower to embrace more liberal reforms.

For a time, there was a real desire to unite Scandinavia into one country and this helped keep the union together. However, mismanagement by the Swedish kings and the declaration by the Swedes in the 1840s that they were in the ‘rightful superior position in the Union’, saw support for the Union drop in Norway. This led to decades of demands by Norway for a more equal partnership with Sweden.

By 1905, the Norwegians had had enough; their lack of progress in renegotiating the union drove some Norwegian politicians to resign and created a political crisis. A referendum was called and many in the Norwegian government declared the union already dissolved.

Norwegian voters were asked if they agreed with the dissolution and the result was 368 208 votes for dissolving the union and 184 against.

Just over a month later, the Union was entirely dissolved, and Norway broke away to become the now Independent Kingdom of Norway, independent for the first time in over 500 years.

Within 35 years, Norway would briefly lose its independence again when it was invaded and occupied by Germany in 1940, but was liberated in 1945.

In 1967, the country discovered oil; today Norway is one of the richest countries on earth despite its tiny population and cold climate.

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend