An environmental writer has got himself in a tizzy over the prospect that Eskom might contract floating, gas-fuelled ‘power ships’ to augment Eskom’s stuttering power supply. As with all projects that aren’t wind or solar, environmentalists fear apocalyptic consequences.

According to Tony Carnie, a freelance environmental writer, a proposal to anchor floating power stations off SA harbours ‘raises alarm bells’. The proposal under consideration by the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE) involves Karpowership South Africa, a subsidiary of Turkish company Karadeniz Energy Group.

Carnie’s objections, for the most part, appear petty and superficial, in line with the well-honed green strategy of placing legal and public opinion hurdles in the way of any energy development that doesn’t fit their extremely narrow view of what ought to be permissible – that being limited largely to wind and solar energy.

The purpose of such objections is to delay, delay, delay, until either renewable energy fills the gap, or the market opportunity for the development evaporates.

A classic example of this strategy can be found in the Karoo shale gas saga, where public relations campaigns and legal action run by well-funded green groups have delayed exploration permits by a decade, a period during which exploration might have been completed and onshore production of cheap, clean natural gas might have started already. This would have given a huge boost to the energy sector, employment and the wider economy – a boost which our sinking economy desperately needs.

Scaremongering

At issue this time is a proposal to contract five ‘power ships’, which are self-contained power stations producing up to 470MW each that can be anchored in ports and feed electricity onto the national grid. Using liquified natural gas (LNG) as fuel, these ships can reliably produce power at a cost of about R1.70/kWh, and save Eskom about R28 billion in a year.

Carnie describes LNG as ‘extremely flammable’, and links those ominous words to a material safety data sheet. I read that sheet so you don’t have to, and would you believe it, LNG really is extremely flammable.

Of course, that’s the entire point of LNG. It’s supposed to be flammable, so you can burn it to heat water to produce steam to drive turbines that generate electricity. That’s how power stations work. They convert heat into electricy. (Well, all the good ones do, at least.)

He reinforces the scaremongering by referring to the recent Beirut explosion, saying two such power ships ‘escaped catastrophe’, because they weren’t caught up in the explosion. Not being destroyed, presumably, shows how unsafe they might have been had they been nearer the largest accidental non-nuclear explosion since 1944.

He says this as if it would have been the fault of the power ships had they been damaged by the explosion. An explosion near any store of fuel is a problem, of course, whether it’s an oil or gas refinery, a liquid fuel storage depot, fuel tanks at a gas turbine power station, or indeed the storage tanks beneath your friendly neighbourhood petrol station. Even your own heater’s 9kg gas cylinder is a bomb waiting to go off, should it be caught up in a house fire.

The risk, in all these cases, warrant adequate design safety features and operating safety procedures. That’s why there are ‘no smoking’ signs at petrol stations, for example. These risks do not, however, merit irrational fear.

Environmental worries

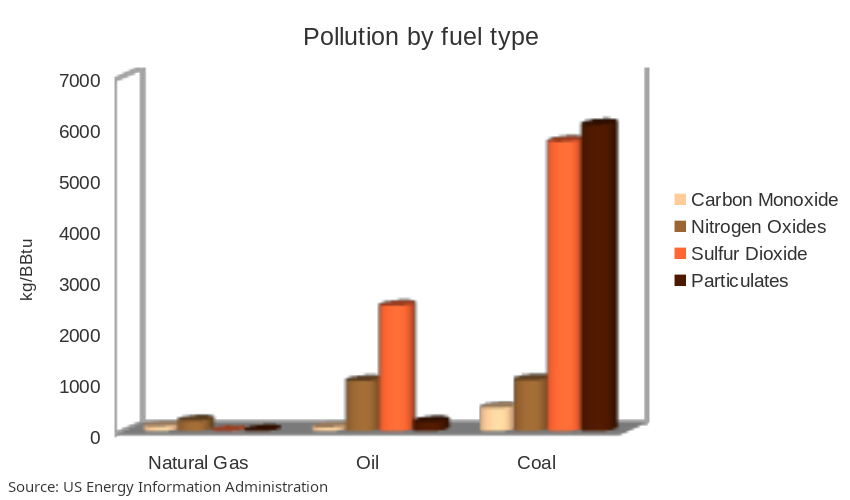

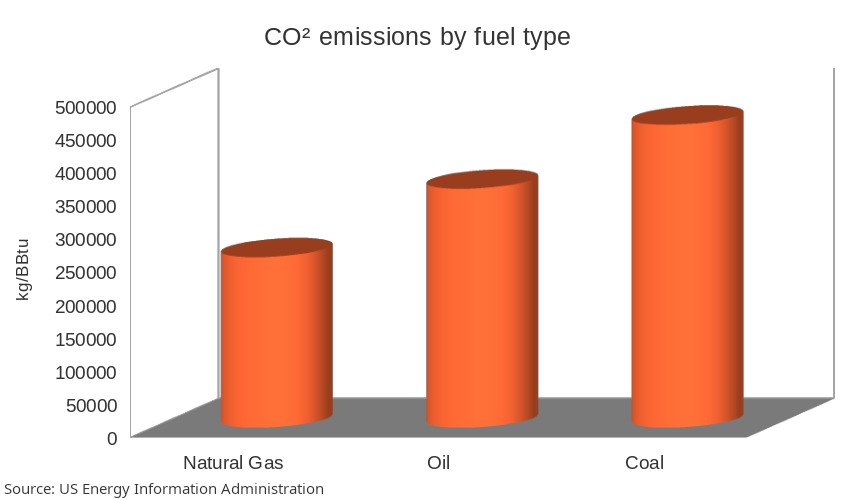

Among the environmental concerns Carnie raises is the risk of air pollution due to the combustion of LNG. What he fails to point out is that LNG is an extremely clean-burning fuel, producing almost no pollutants when compared to diesel, which Eskom uses to fuel open-cycle gas turbine (OCGT) power stations. Eskom’s OCGT power stations are supposed to run on gas to provide peaking power, but have lately been run 24/7 on diesel just to keep the lights on.

Burning natural gas in power stations virtually eliminates the pollutants that are produced by burning oil or coal, and also produces far lower carbon dioxide emissions.

Running OCGT power stations at full tilt on diesel is not only bad for the power stations, but it is also extremely expensive.

Eskom has not yet released its integrated report for the year ending 31 March 2020, but for the prior year, it reported the unit cost of OCGT electricity at R3.13/kWh, which is almost twice the unit cost of R1.70/kWh offered by the Karadeniz power ships. The power ships also come in below the R2.06/kWh Eskom says it costs to procure electricity from renewable independent power producers.

If power ships can help to relieve the pressure on OCGTs, Eskom – and the country – would be much better off.

Another of his environmental concerns is ‘the ecological impacts of discharging salt-laden brine water and hotter water on sensitive sea and estuarine creatures’. While this might present some issues, it is no different from the impact of any other coastal power station, including the OCGTs. The sea is a big place, and any localised excess salinity or heat quickly dissipates. One cannot really describe an active harbour as a sensitive sea or estuarine environment in any case.

Emergency directive

Carnie’s main gripe appears to be that Karpowership South Africa applied for, and received, a directive in terms of Section 30 of the National Environmental Management Act (NEMA), which exempts those responding to ‘emergency incidents’ from having to comply with the full set of environmental rules and regulations.

Of course, having to comply with all the bells and whistles of NEMA, even when the risks are clearly minimal, would delay the commissioning of the ships. This goes against a stated criterion set by the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE) in 2019, when it asked for proposals. It wants suppliers of between 2 000MW and 3 000MW of electricity who are able to connect new plants with very short lead times (as little as three months). Elaborate environmental impact assessments, public consultation, and related regulatory niceties would make such lead times impossible.

One can see why this raises red flags among the ‘environmentalists and law experts’ of Carnie’s acquaintance, some of whom would be conducting these processes and producing these reports at hefty hourly rates.

The apparent grounds for the emergency directive is that unreliable power supply has a detrimental impact on the country’s response to the Covid-19 disaster.

Carnie has a point when he says this link seems tenuous, and could open the door for similar argument for any number of projects that have some impact on the progression of, or response to, Covid-19. However, it does seem reasonable to suppose that Eskom’s inability to prevent loadshedding and load reduction, even during the massive economic depression caused by the lockdown, has a direct, negative impact on healthcare facilities and other essential suppliers to the Covid-19 response.

The Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries (DEFF) evidently agreed with Karpowership South Africa that rapidly providing additional electricity to Eskom merited an expedited environmental process.

Carnie was unable to solicit any explanation from either the DEFF or the DMRE, so we’re left only with the protestations of the very people who would profit from a lengthy environmental impact assessment process, whose friends in wind and solar would benefit from less competition from natural gas, or for whom any delay in a fossil fuel energy project suits their ideological agenda.

Over-regulation chokes the economy

Over-complicated environmental compliance processes add significant costs and delays to projects that would contribute to the development of the South African economy. Over-regulation, lack of regulatory capacity, and the consequent endless litigation by green lobby groups and environmental lawyers contributes to keeping the country’s economy depressed.

Every year a project is delayed is a productive year lost, not only to the project owners and their would-be employees, but also to the rest of the country in terms of trade, and in this case, electricity.

Every hour of loadshedding costs the country R150 million. Every hour of loadshedding avoided, saves the country R150 million. That is the real emergency that, to my mind, justifies an expedited environmental approval process for new energy projects such as these LNG-fuelled power-producing ships.

I think they’re a splendid idea. Next stop: nuclear power ships.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend