This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

23rd of August 30 BC – After the successful invasion of Egypt, Octavian executes Marcus Antonius Antyllus, eldest son of Mark Antony, and Caesarion

Egypt, one of the world’s oldest civilizations, had been ruled by the Greek Ptolemaic dynasty for almost 300 years by 30 BC. Indeed, since the final Persian conquest in the 340s BC, Egypt had been ruled entirely by foreign kings.

In 305 BC, one of the Macedonian generals who had served with Alexander the Great, Ptolemy, had taken control of Egypt during the chaotic aftermath of Alexander’s sudden death and had established himself as the new king of an independent Egypt.

For centuries now his descendants had ruled Egypt as half-Greek kings, half-Egyptian Pharaohs. The Ptolemaic kingdom established itself as an important player in Mediterranean affairs. The Greek-Egyptian kingdom became wealthy, supplying lots of grain from Egypt’s fertile farms to Italy and Greece, advancing science and discourse by establishing the famous library of Alexandria, constructing the great lighthouse of Alexandria, fusing Greek and Egyptian sculpture and art, and building a powerful navy.

However, their endless wars with the other great Greek successor states of Alexander’s empire weakened them, as did internal conflict and intrigue. By the last century BC, Ptolemaic Egypt was a shadow of its former self. Its weakness coincided with the emergence of a new power in the region, the Roman Republic, which was expanding into the Eastern Mediterranean. Egypt was forced to ally itself with Rome to avert conquest by the Roman war machine, and, by 48 BC, the Romans had gained enormous influence over the government and finances of Egypt. The Roman senate had even been named as the executor of the will of the Pharaoh upon his death.

Rome, however, was experiencing great turmoil itself, and, in 49 BC, the Roman general Pompey Magnus (the great) had fled from defeat at the hands of his opponent, Julius Caesar, to seek refuge in Egypt where he thought his friends in the Egyptian government would protect him. Unfortunately for him, the ruler of Egypt, the child king Ptolemy VII (who was married to and co-ruler with his 22-year-old sister Cleopatra VII), saw which way the winds were blowing and, seeking favour with Caesar, cut off Pompey’s head and presented to Caesar.

Caesar was horrified by this gesture, partly because he didn’t much like the idea of foreigners killing a Roman consul, but also because he had planned to exonerate Pompey to demonstrate his magnanimity, a favourite political trick of Ceasar’s. This moment is captured wonderfully in the HBO series, Rome (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r75FmMPKOAg)

Nevertheless, after being seduced by Cleopatra, Caesar decided to effectively make her the sole ruler of Egypt.

Cleopatra and her husband/brother had been engaged in a civil war for control at the time of Caeser’s arrival. After some tough fighting, Caesar’s troops crushed the Egyptian army loyal to Ptolemy – the young Ptolemy drowning in the Nile as he tried to flee. In the romance that followed, Cleopatra claimed to have gotten pregnant with Caesar’s child, a boy she called Caesarion, making her the only mother of a potential male heir of Caesar.

When, in 44 BC, Caesar was murdered by the Roman senate and a new series of civil wars erupted in Rome, Cleopatra sided with Caesar’s lieutenant Mark Anthony, with whom she began a romantic relationship. The other emerging side in the civil war was led by Caesar’s great-nephew and heir, Octavian, later known as Augustus (after whom the month of August is named).

Octavian and Mark Anthony eventually agreed to a truce, splitting the Roman world between themselves, with Octavian getting the west and Mark Anthony the east. Octavian’s sister married Mark Anthony. This did not last, however; Mark Anthony was far more interested in his Egyptian mistress, Cleopatra, than his Roman wife, a fact used to great political effect by Octavian in Rome. Soon, Octavian once more declared war on Mark Anthony.

After a sea battle at Actium in Greece, Mark Anthony and Cleopatra’s Roman-Egyptian navy was destroyed by Octavian’s forces, and the two lovers set off for Egypt to try and rescue their dire situation.

Despite an initial desire to fight, morale was low, and Mark Anthony’s army was ultimately smashed by Octavian in 30 BC. Shortly after this defeat, Mark Anthony committed suicide. Cleopatra, realising she would not be able to charm Octavian, followed suit, committing suicide on 12 August 30 BC rather than allow herself to be humiliated by the Romans.

On 23 August, Mark Anthony’s son, Marcus Antonius Antyllus, was executed by Octavian, along with Caesarion, Octavian’s only rival for the title of Caesar’s heir.

Shortly afterwards Egypt was declared a Roman province, ending its independence. It would remain under Roman rule for the next 670 years.

25th August 2012 – Voyager 1 spacecraft enters interstellar space, becoming the first man-made object to do so

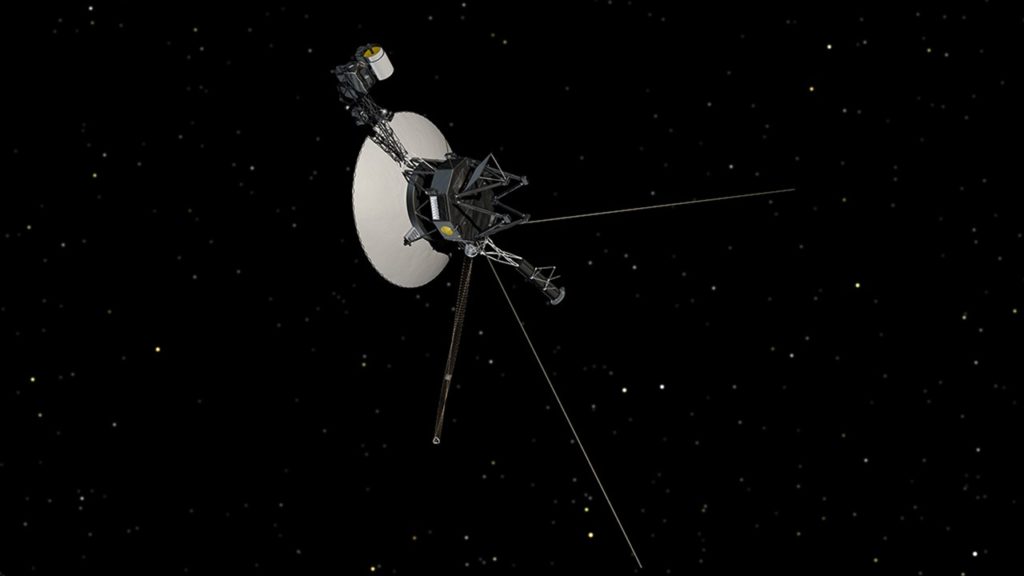

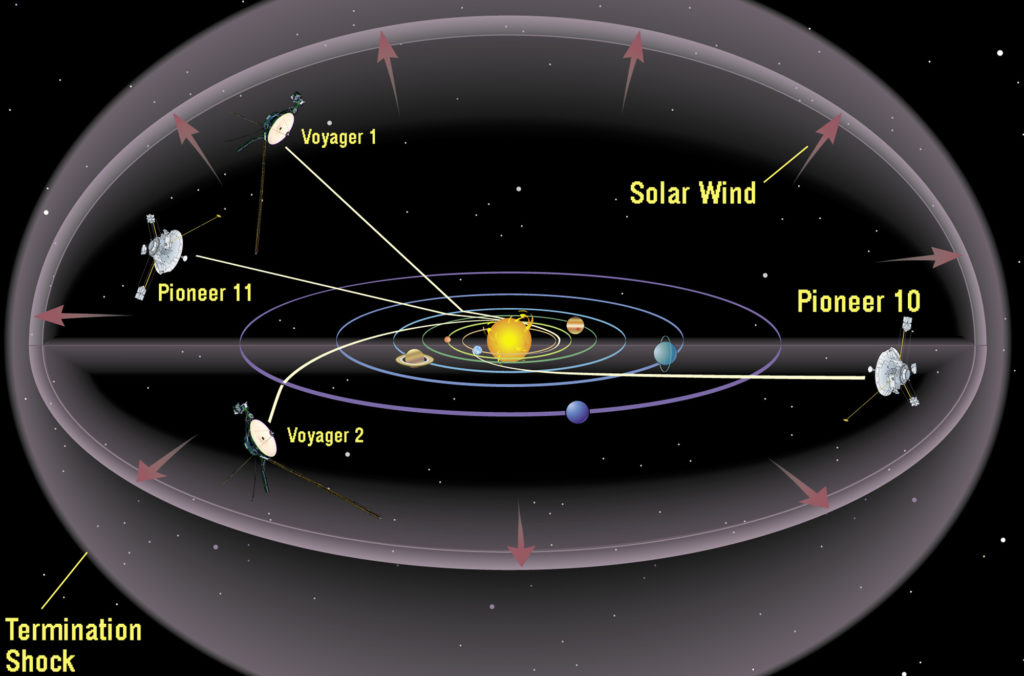

On 5 September 1977, the Voyager 1 spacecraft was launched on a mission to study the outer solar system. The probe’s objectives included fly-bys of Jupiter, Saturn, and Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The craft also carries a record of life on earth and contains pictures of a human male and female along with sights and sounds of earth, all burned onto a golden disk.

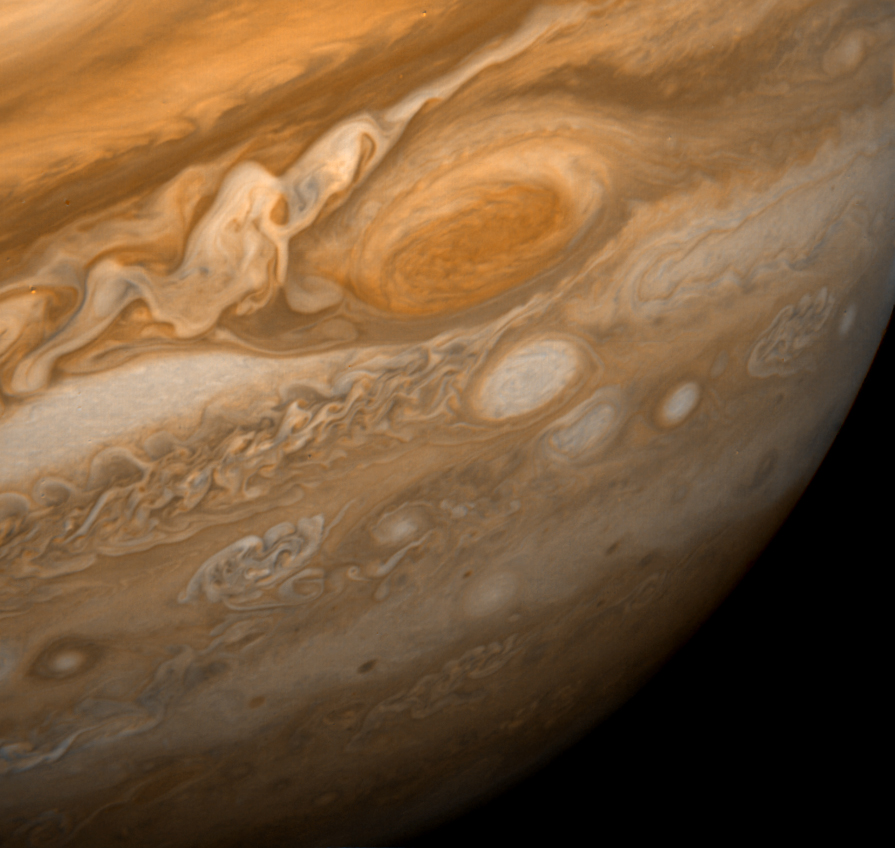

In January 1979, the probe passed Jupiter, taking spectacular photographs of the planet and its many moons, which helped reveal much about the geography of planets and moons in our solar system.

In November 1980, Voyager 1 encountered the gas giant Saturn, photographing the planet’s magnificent rings, and Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, suspected by some to potentially hold life under its hazy clouds.

In 1998, Voyager 1, travelling at about 17 kilometres per second, overtook Pioneer 10 (launched in 1972) to become the furthest spacecraft from earth.

On 25 August 2012, Voyager finally passed beyond what is considered the solar system and entered interstellar space, the first spacecraft to achieve this. Today, the Voyager is far and away the furthest human-made object from earth. While its systems are gradually being shut off to conserve what little power it retains, the craft is expected to keep operating until around 2025.

27th August 1896 – Anglo-Zanzibar War: The shortest war in world history (09:02 to 09:40), between the United Kingdom and Zanzibar

Growing British influence in East Africa – along with a treaty signed with Germany – had placed the then independent sultanate of the island of Zanzibar more and more under the control of London. The British had begun to influence the island government, including deciding who would become the sultan, and pushing for a crackdown on the slave trade.

In 1890, a new Sultan of Zanzibar had banned the slave trade, but not ownership of slaves, and made Zanzibar a protectorate of the British Empire.

However, the Arab elite of Zanzibar had been involved in the ancient East African slave trade for centuries and, for many of them, it remained an important source of wealth. Slave raids along the African coast had supplied India and the Middle East with slaves since the first centuries AD or possibly earlier.

The Arab elites saw very little reason why the arrival of these foreign imperialists should disrupt one of their most ancient and established trade arrangements, and they sought to throw off British rule. On 25 August 1896, the pro-British Sultan Hamad bin Thuwaini suddenly died – he was possibly was murdered – and a new candidate, Sultan Khalid bin Barghash, seized the throne without British approval.

The British garrison on the island was disturbed by this turn of events and the mustering of pro-sultan troops armed with rifles and muskets at the royal palace, as well as some artillery, placed on the palace walls.

The British telegraphed the government in London, and permission was granted for the use of force to remove the new sultan if a diplomatic solution could not be reached.

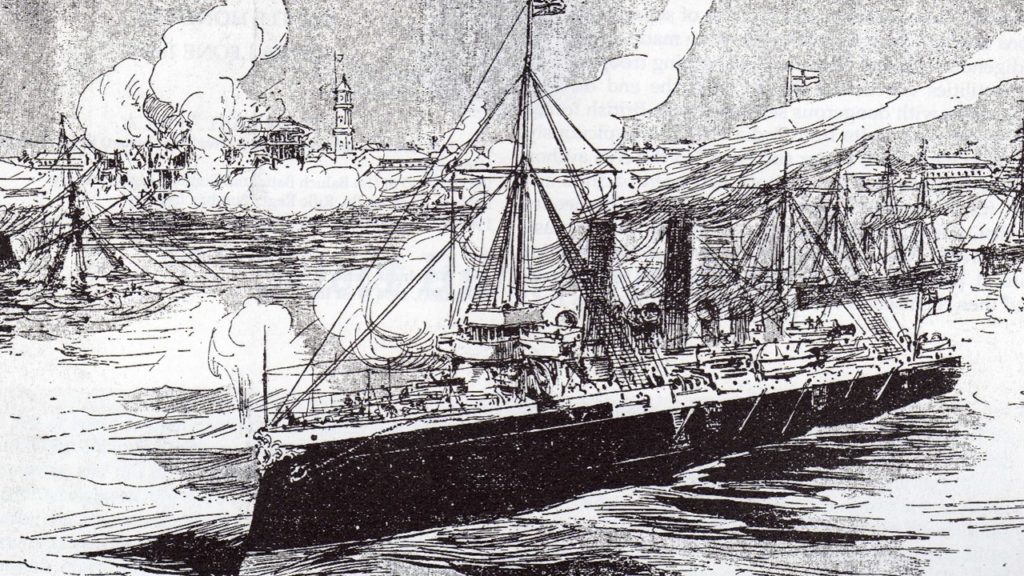

A day later, on 26 August, a squadron of British naval vessels arrived in the harbour and an ultimatum was issued to the sultan demanding he take down his flag and leave the royal palace by the next day.

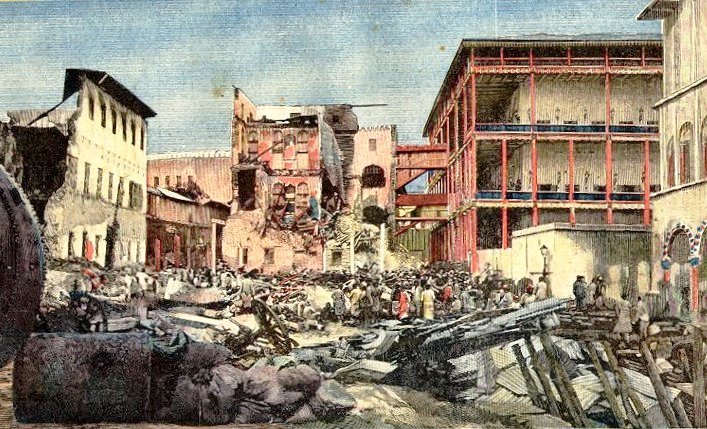

At 9:02 on 27 August, the British ships opened fire on the palace and surrounding areas, and some 1 000 British troops, mostly Askaris, advanced towards the palace.

The shelling from the ships proved effective and, within minutes, the Sultan Khalid and many of the Arab elite abandoned the palace leaving their slaves and servants to keep fighting. At 9:40, the shelling ceased. There was no more fighting, with the leaders having fled, but a fire raged in the palace and adjoining harem.

Around 500 Zanzibari men and women were killed in the shelling and resulting fire. Only one British sailor was wounded. Most of the Zanzibari population sided with the British over the immediately appointed Sultan Hamoud bin Mohammed Al-Said, and there was no resistance to the British troops as they occupied the town. The war was over in 38 minutes, the shortest war in recorded history.

There was some looting in the chaos of the shelling of the Indian quarter of the city by locals from other areas and around 20 people were killed before order was restablished.

The British sent 150 Sikh troops to restore order to the streets and put the rest of their force to work helping the locals to put out the fire which was spreading from the palace.

The defeated Khalid fled to the German consulate, where he was sheltered as an asylum seeker and later transferred to German East Africa. He would be captured there by the British in 1916 during the First World War, exiled to Seychelles and later St Helena before being allowed to return to East Africa, where he died at Mombasa in 1927.

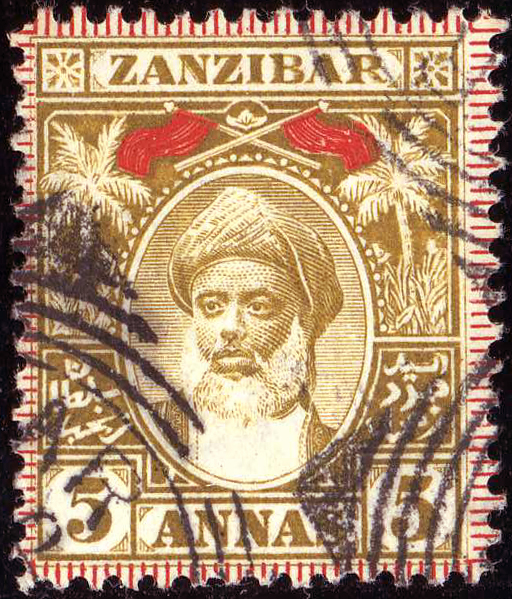

Sultan Hamoud acted as the figurehead for the British government until his death in 1902. There were no further rebellions on the island until the British left in 1963.

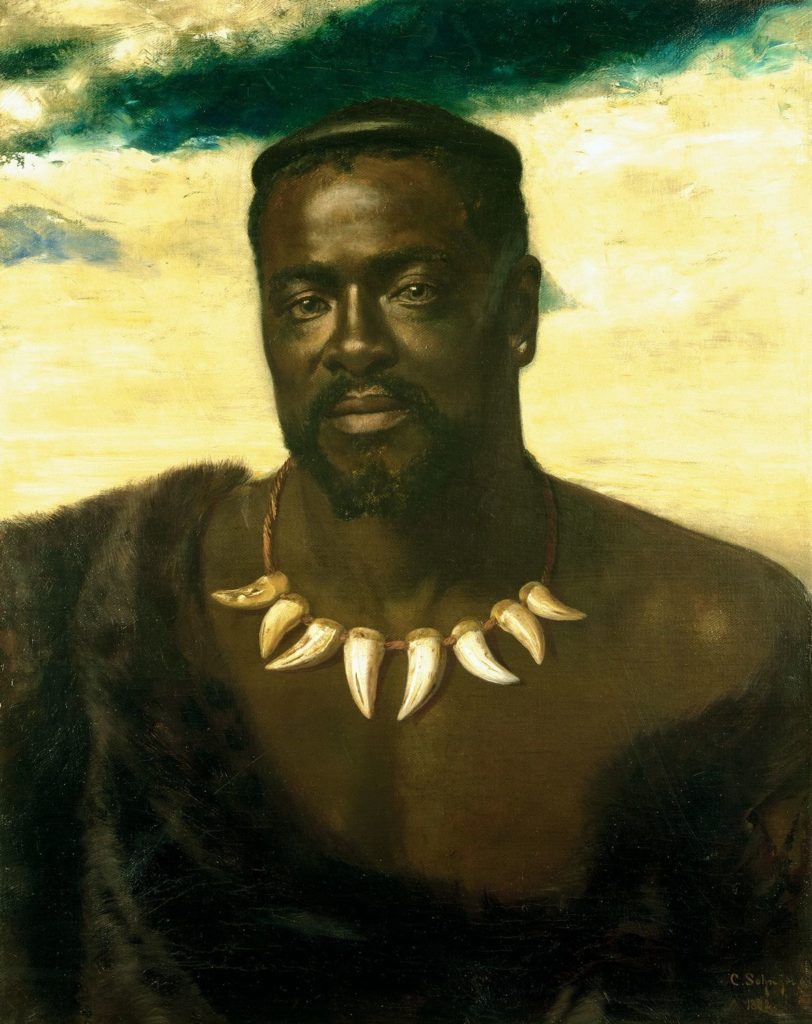

28th August 1879 – Cetshwayo, last king of the Zulus, is captured by the British

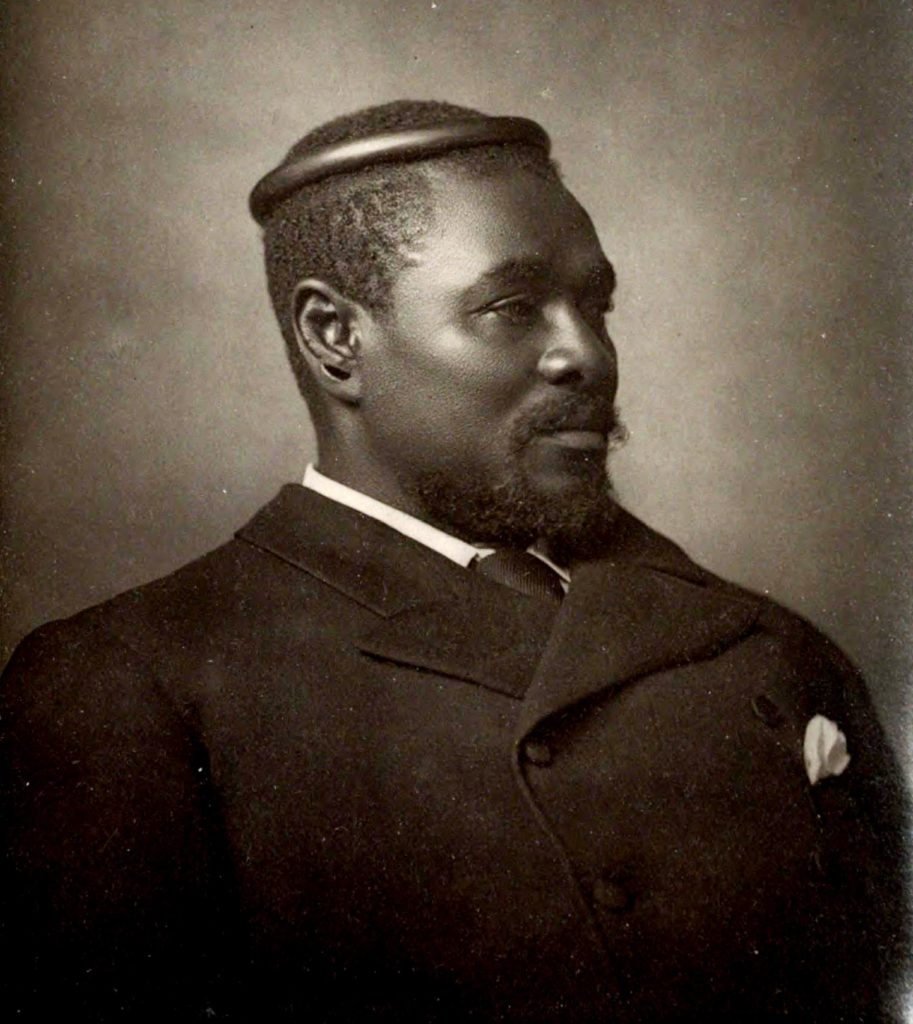

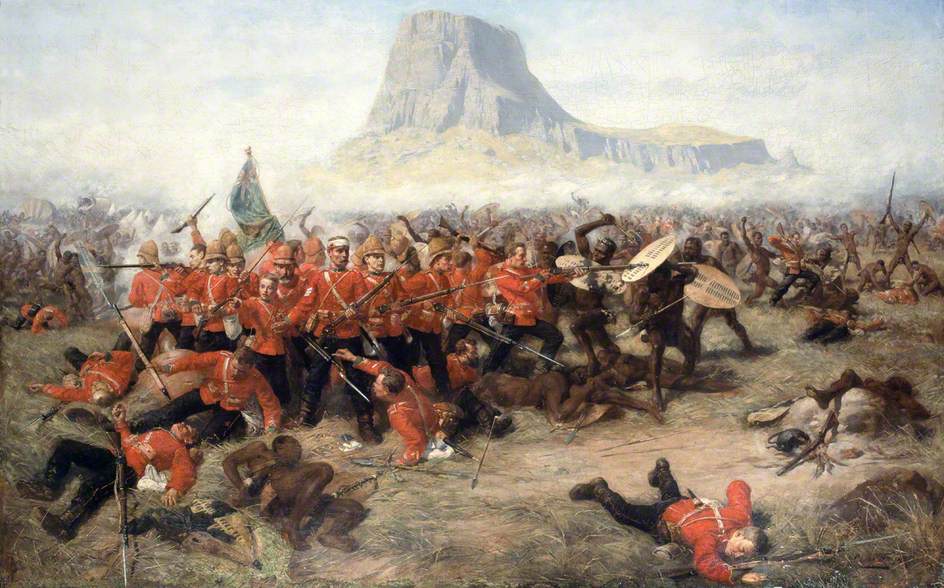

The last independent king of the Zulu people, Cetshwayo kaMpande, is most often remembered for the triumph of his armies over the invading British armies at Isandlwana in 1879, or their subsequent defeat at the battle of Rorke’s Drift the next day.

However, King Cetshwayo’s story has much more to it. He originally came to power after defeating his rival for the throne, his younger brother and father’s favourite, Mbuyazi, at the battle of Ndondakusuka in 1856. In this engagement, Cetshwayo trapped his brother’s smaller force of around 7 000 warriors against the Tugela River, where his army of 20 000 defeated them and massacred the families travelling with them.

Cetshwayo’s father, Mpande, was still alive, but resentfully accepted his oldest son’s claim to the throne, living his remaining years a much-diminished figure before finally dying in 1873.

After their defeat at Isandlwana in January 1879, the British would return to Zululand with a reorganised force and, in July, defeated the Zulu army at the Battle of Ulundi, capturing and burning the royal kraal.

Just over a month later, the British would finally capture Cetshwayo. He was first exiled to Cape Town and then to London, where he stayed for a time. While in London he managed to gather the support of some prominent British political figures and a journalist of the London Morning Post. Many in London soon came to regard Cetshwayo’s treatment at the hands of British officials in South Africa as unfair.

In 1882, Cetshwayo met Queen Victoria and requested he be returned to Zululand and reappointed king of the Zulus, promising not to fight the British again.

In his absence, the Zulu clans, no longer united by a strong central figure, had begun to fight each other in a brutal civil war. Hoping that Cetshwayo might end the conflict, the British sent him back to Zululand in 1883 and restored to him some of his territory.

Rival Zulu clans, not keen on being under the thumb of the king again, hired some Boer mercenaries and attacked Cetshwayo’s new kraal and forced him into hiding in the woods near Nkandla. He was wounded in the attack.

Cetshwayo then moved to Eshowe, where he died of what was likely a heart attack in February 1884.

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend