Former Finance Minister Trevor Manuel said of South Africa recently that ‘almost three decades were wasted’, and Stats SA indicated that the economy had halved. Both statements have been walked back, despite probably being correct on the bigger picture.

This week Stats SA released its GDP numbers for the second quarter of 2020 to a great wailing and gnashing of teeth. In inflation-adjusted terms, GDP fell 17.1% from the previous quarter, which makes for the headline 51% drop on an annualized basis.

What followed has been, as ex-President Zuma’s counsel might say, ‘a ding-dong thing‘. One side says the economy has halved; the other calls this unduly negative, pointing out that the -51% ‘annualized’ drop would mean the next three quarters would have to shrink at the same rate of decline as the last, which is highly unlikely.

To gauge the problem, it is worth recalling a statement by Trevor Manuel a few weeks ago. ‘History casts a long shadow over what we do. The big challenge that confronts us in South Africa is what we do now, with almost three decades that were wasted.’

Disciples of the ANC denounced Manuel for providing a ‘doom-laden picture’. Manuel then walked back the statement, even calling for the original report on Fin24 to be retracted.

In response, Fin24 published the video of Manuel clearly stating ‘almost three decades were wasted’. Another ‘ding-dong’ with a real message lost in the noise.

Both news cycles started with a hard ding of bad news followed by the ‘dong’ backlash that pessimists are distorting facts to play politics. What is really going on?

Economy halved

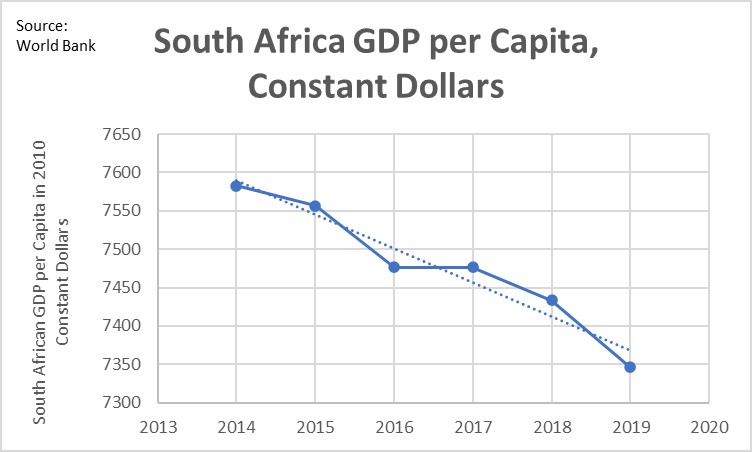

From 1999 through the 2000s, the ANC (mostly) ran a fiscally disciplined administration while expanding a highly ill-disciplined patronage network. For a time, this flabbergasting contradiction could coexist with overall growth. In constant dollars, GDP per capita increased by 25% from 1999 to 2009 (and recall that 2009 was a dip; growth looked even better before that).

Had we continued on that trend, the economy in 2019 would have delivered roughly $10 000 per capita (in 2010 constant dollar terms) rather than $7 350 per capita (in the same terms). In other words, South Africa would have been about 35% more productive in 2019 than it actually was, had we merely continued at that pace.

This would have required reforms in the 2010s rather than the election of Zuma, but it is a good measure of where we could realistically have expected to be by 2019 rather than where we are.

Add to that missing 35% the latest 17% quarter-on-quarter drop in 2020, on the back of one of the world’s harshest and most irrational lockdowns, and following three recessionary quarters before that, and it all adds up to something quite dramatic. The thought that South Africa’s economy today is half the size it should have been is not so much fanciful as tragic.

30 years wasted

It is possible that Manuel misspoke when he said ‘almost three decades were wasted’ but it is worth seriously considering the possibility that he meant what he said, only to retract it under pressure thereafter.

In the original discussion, Manuel distinguished between ‘wasted’ years and the ‘lost decade’, which makes sense. If you lose something today it wastes earlier work to buy the thing and undermines potential for the future.

National efforts to reduce the debt burden to around 28% of GDP in the 2000s (led by Manuel himself) were squandered under Zuma and Ramaphosa. The present, embattled, finance minister, Tito Mboweni, showed that debt-to-GDP was expected to reach 80% this year and over 100% by the next national election. That is called wasted gains.

Moreover, damage done now to the Rule of Law, the Constitution, investor confidence and skills will long outlast the next four seasons. Manuel knows this very well too, his most exemplary functions at the Treasury (and in business) having been budgeting, which is a future-oriented lens through which to analyse potential lost or gained. Manuel knows exactly what wasted potential is.

Wasted gains is what we have lost and wasted potential is what we sadly face. Hence ‘three decades were wasted’ may be the most honest appraisal by a top ANC member to date. The period from 2000 to 2030 are our three decades of waste, the gains of the first lost to the second which has already constrained potential for the third.

This interpretation was entirely overlooked, which is a mistake.

False Promise

One way to notice how easily we are tempted to underestimate how much potential has already been wasted is to reflect on the following graph.

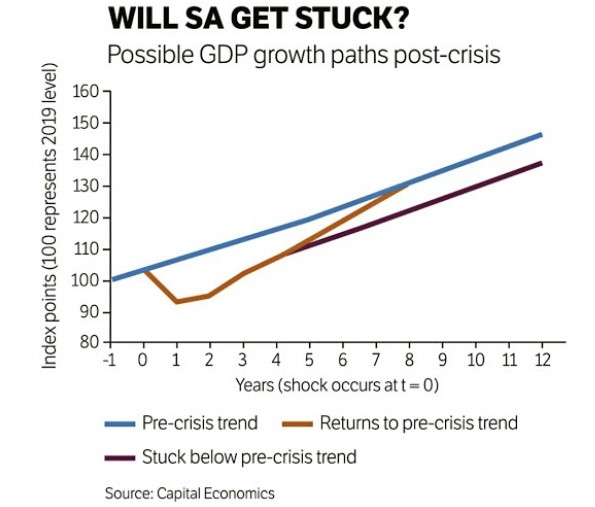

This graph was published in a BusinessLive piece called ‘SA on the wrong side of recovery hopes’ by Financial Mail economics editor Claire Bisseker. The headline is about as gloomy as could be and the piece is generally excellent. That is why I am picking on it. Even when trying to make a case for our being probably ‘stuck’ on the ‘wrong side’ of recovery, the graph Bisseker includes is titled ‘towards false hope’.

The ‘pre-crisis trend’ in the graph above, indicating a jollier life before Covid-19, has South Africa on a 4% growth per annum trajectory, using obscure ‘Index points’.

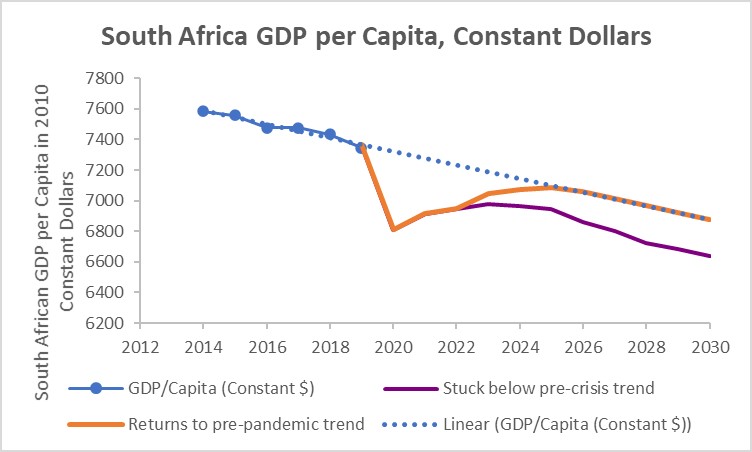

Look at things in constant dollars on a per capita basis and you see how bad the later Zuma and Ramaphosa years have been. The prospect is grim, but better to confront than ignore it. Applying Bisseker’s two-paths-to-recovery model, we see the following.

On this picture the ‘good’ option is to return to recession that leads into depression while the ‘bad’ option is to skip the recession part and just get depressed immediately. This is what South Africa has to face, and one better face it with both eyes open.

The open question

How long will it take us to return to our 2014 peak in real, per capita terms? The answer to that question is not fixed, for it is to be determined by decisions still to be made.

My astute colleague John Endres recently authored an IRR report setting out how the policy and administrative backdrop could be genuinely reformed to kick South Africa into a positive gear, realising 7% GDP growth within a decade. It is serious, and seriously promising.

It is also another way of saying it could take a decade to get from our ultimate dip back to our previous peak.

Delay the inflexion point to this kind of reform much longer and acknowledging Manuel’s view that ‘almost three decades were wasted’ will no longer be taboo. It will become common knowledge.

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend