This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

4th October 1582 – The Gregorian Calendar is introduced by Pope Gregory XIII

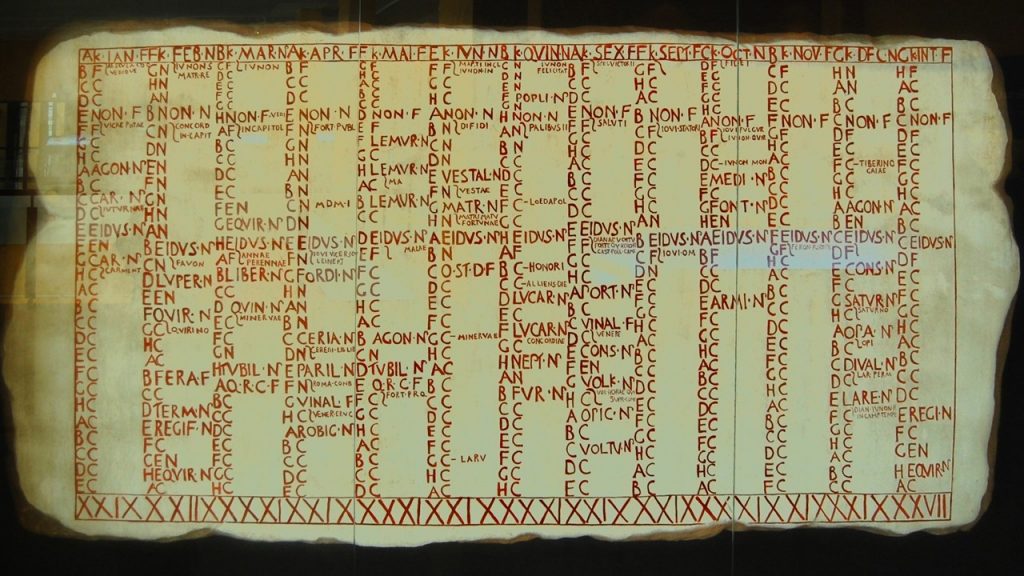

In 46 BC, the Roman general and politician, Julius Caesar, introduced some urgently needed reforms to the calendar used by the Romans. As the calendar did not account for the fractions of a day in the solar year, the months of the year had slowly drifted so that it was completely out of sync with the seasons. Caesar, using insights from Greek science, reformed the calendar, introducing a normal year of 365 days and a leap year of 366 days once every four years to account for the slow drift.

While it was an enormous improvement on the old system, the Julian Calendar, as it came to be known, did have some small problems.

One problem was that it did not entirely halt the drift, because the 365.25 days of the Julian Calendar slightly exceeded the actual solar year value of 365.24219 days, which meant the Julian Calendar gained a day every 128 years.

Despite this, the Julian Calendar became the standard for Europe and the Christian world for over 1 500 years.

However, as the centuries passed, the Catholic Church became increasingly worried by the slow drift of the year, particularly with regards to the timing of Easter, which, unlike other Christian festivals, was tied to the Spring equinox rather than being on a set date. However, it was also supposed to occur around the month of March, but, due to the error in the calendar, the Spring equinox was drifting further away from March.

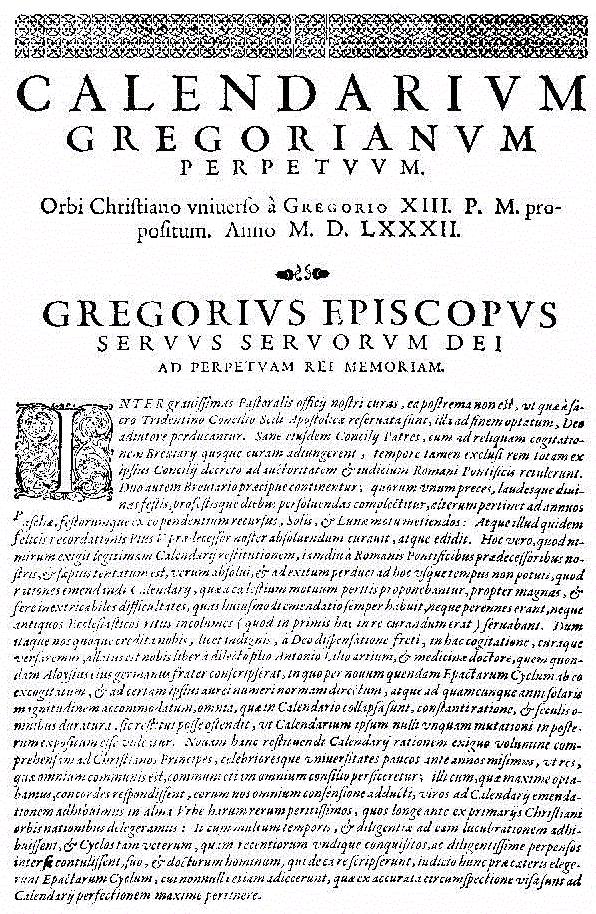

This problem had been known since the 8th century. A few attempts to reform the calendar had all failed for various reasons, and it was not until the pontificate of Gregory XIII that the problem would be properly addressed.

The Catholic world in the 16th century was aflame due to the emergence of the Protestant Reformation. When the Catholic Council of Trent was summoned to respond to the Protestant movement in 1545, it also approved the creation of an updated calendar.

After years of debating the problem, a Compendium was sent out to mathematicians around the Christian world in 1577 asking for comment on how to solve the problem. The eventual reform adopted was a modification of a proposal made by the Calabrian doctor, Aloysius Lilius (or Lilio).

Lilius’s work was expanded upon by Christopher Clavius in a closely argued 800-page volume. Clavius’s opinion was that the correction should take place in one move, and it was this advice which prevailed with Pope Gregory.

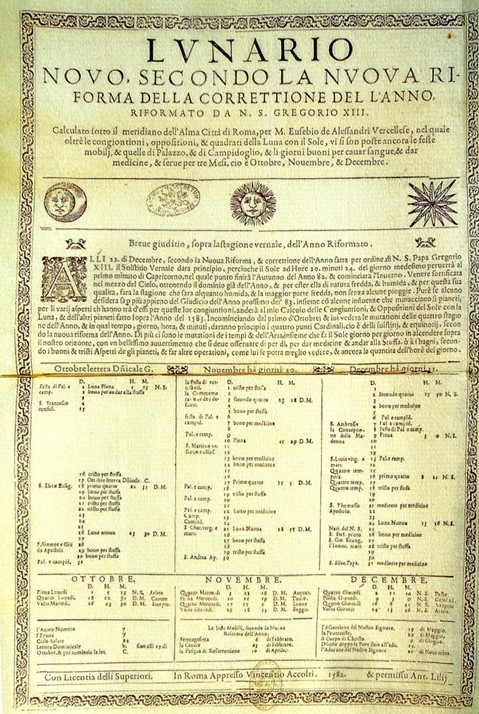

The new calendar, soon to be called the Gregorian Calendar, shortened the average (calendar) year by 0.0075 days to stop the drift of the equinoxes. To deal with the drift since the Julian Calendar was fixed, the date was advanced 10 days; Thursday 4 October 1582 was followed by Friday 15 October 1582.

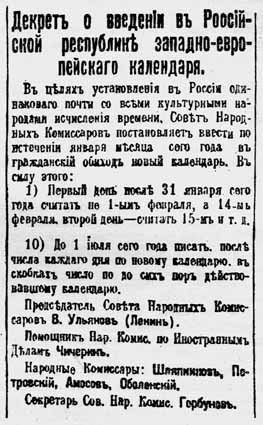

The new calendar was slow to be adopted outside of the Catholic world; famously Russia only adopted it in the 20th century, which is why the ‘October Revolution’ of 1917 – according to the Julian Calendar – actually happened in November.

Greece was the last European country to adopt the Georgian Calendar.

Today, most countries in the world use the Gregorian Calendar for civil purposes, even in non-Christian countries. Despite its improvements, the Georgian Calendar is still slightly inaccurate and will add one day per 3,030 years.

5th October 1910 – In a revolution in Portugal, the monarchy is overthrown and a republic is declared

Once a great power of Europe with a powerful colonial empire, the Kingdom of Portugal had been in relative decline for centuries by the beginning of the 20th century. Originally sparking much of the exploration, trade and conquest that Europe had embarked on since the 15th century, Portugal steadily lost ground to Spain, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and France until becoming something of a backwater in European affairs by 1900.

The crisis which would end the Portuguese monarchy began in 1890 when the British government, for centuries Portugal’s ally, demanded that Lisbon withdraw all its military forces from the region between the Portuguese colonies of Angola and Mozambique.

This area in what is today Zambia and Zimbabwe, was claimed by Portugal and gave it a swathe of territory across the whole width of Southern Africa.

The Portuguese government, seeing no hope of resisting the British, capitulated. This was seen as an embarrassment and a national humiliation and began to erode the monarchy’s prestige, both among the elite and the ordinary people.

Over the next two decades, the republican movement in Portugal attacked the enormous expenses of the royal family and managed to frame the monarchy and its supporters as the agents of ‘backwardness’ and portray republicanism as the force for ‘progress’.

From 1890, Portugal experienced several crises and much political dysfunction as the two main political parties of the monarchy, the Progressive and Regenerador parties, fought bitterly for control of the government. In 1907, the Regenerador politician, João Franco, established an authoritarian government, which was unpopular.

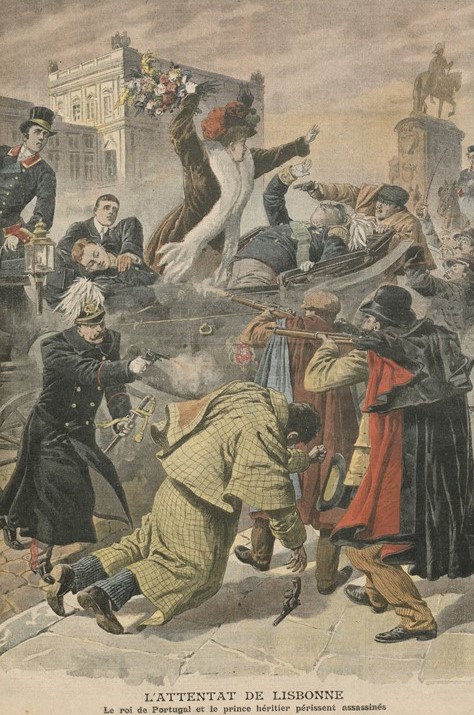

The crisis of the monarchy came to a head in 1908 when the king, Carlos I, and his heir, Luís Filipe, were murdered by republican sympathisers.

The instability that followed saw João Franco deposed as dictator.

The new king, Manuel II, was only 18 at the time and struggled to provide much leadership in the political turmoil following the murder of his father and brother. The republican party of Portugal resolved at its congress of 1909 to overthrow the monarchy by force. The stage was set.

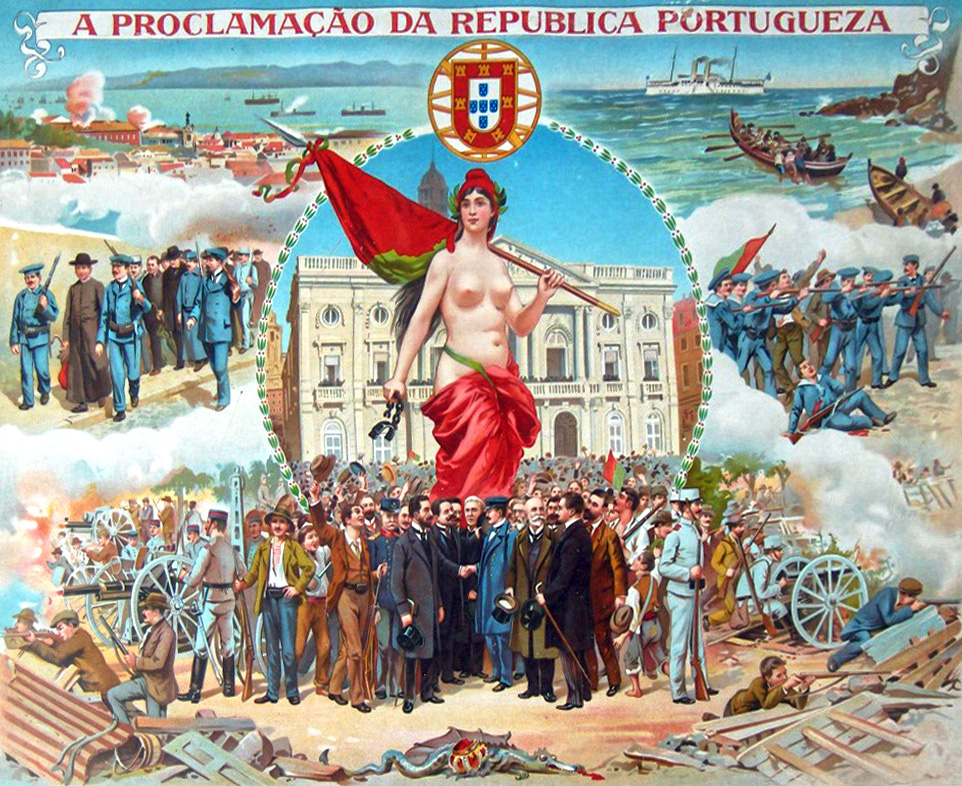

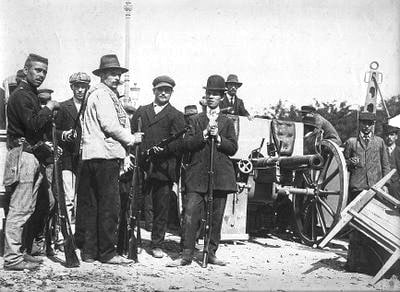

On 3 October the republicans launched their rebellion. Using groups of pro-republican soldiers, they marched on the capital, Lisbon.

The rebels also managed to capture some warships whose guns they would use to support their attack.

Unfortunately for the rebels, some republican leaders at first refused to back the revolt and the numbers of rebels remained fairly small. However the monarchy was slow to organise its troops, some of whom were sympathetic to the republicans, and failed to summon enough force to crush the rebellion. There were clashes throughout 4 October between royalist and republican troops, but a stalemate ensued. Late in the day the morale of the troops loyal to the king collapsed due to shelling by the ships allied to the rebels, and the lack of reinforcements.

The populace, thinking the royalist troops were about to surrender, poured out into the streets to celebrate the new republic; the sight of so much support for the rebellion broke the resolve of the monarchy and the king fled Lisbon.

The republicans declared the new Republic of Portugal on 5 October 1910. The new republic would last until 1926, when it would be overthrown by a military coup d’état.

8th October 1480 – The Great Stand on the Ugra River puts an end to Tartar rule over Moscow

In last week’s edition, I covered the Russian conquest of the city of Kazan and the defeat of the Kazan Khanate. This week, we will discuss one of the major events that led to the Russian triumph at Kazan.

In 1237, the Mongol empire – with troops under the command of Batu Khan, a grandson of Genghis Khan – had arrived at the Russian principality of Ryazan, which they besieged and soon captured, massacring the inhabitants. At the time, Russia was divided between many warring Slavic princes, descendants of Viking chiefs who had settled in Russia and assimilated into the local Slavic culture.

The Mongols next attacked the principality of Vladimir, and smashed its army, once again slaughtering the Russian people of the area. Over the next few years, the Mongols crushed all the Russian princes and either killed them or forced them to pay tribute in the form of gold and troops to the Mongol army.

In 1259, the Mongol empire fragmented and the part of the empire which covered the Eurasian plain – from modern-day eastern Kazakhstan to modern day Romania – was ruled by Batu’s family and became known as the Golden Horde.

The Mongols developed their tributary system across Russia and not only demanded troops and money but also the power to decide who could sit on the throne of the Russian principalities. In some cases, such as in the area around Kiev, the Mongols ruled directly.

By the end of the 13th century, the Mongols began handing over tax collecting duties to the Russian princes and then appointed a chief tax collector from among the princes. At first this was the Prince of Tver, but later (after some rebellions by the Russians), they passed it to the Prince of Moscow.

The Golden Horde lost control of western Ukraine to Poland in 1349, precipitating their decline. In 1363 they lost control of central Ukraine to the Lithuanian grand duke and their power began to weaken. During the 1400s the Golden Horde began to fragment, breaking apart into the, Kazan Khanate, Crimean Khanate, and Astrakhan Khanate with the core of the Golden Horde reforming into the ‘Great Horde’.

During this time of fragmentation, the Prince of Moscow became more powerful and began challenging the weakened Great Horde’s ability to demand tribute from the Russian princes. In 1476, the Muscovites finally refused to pay tribute to the Great Horde and allied themselves with the Crimean Khanate.

In 1479, trouble between the Muscovite prince and his brothers made them look weak and so the Great Horde’s khan decided to march his army towards Moscow to try and force them to resume tribute.

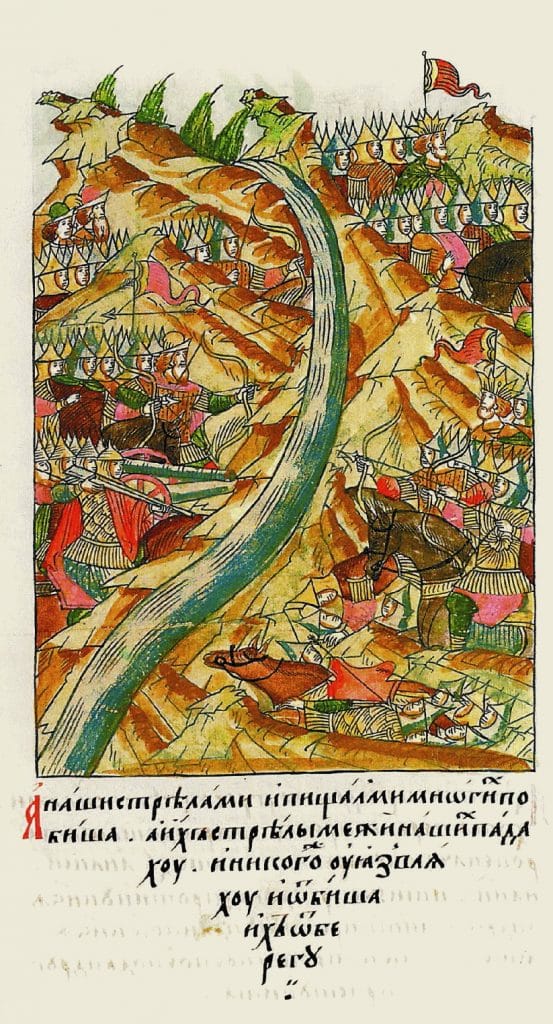

The Russian army faced the horde across the Ugra River and the two sides engaged in a tense stand-off, beginning on 8 October 1480. The Horde attempted to cross the river several times but their arrows couldn’t reach across the river, and the Russians’ muskets picket off their men as they tried to swim across.

With winter approaching, however, the Russians feared that when the river froze the horde would cross and defeat them.

As November approached, the Russians reinforced themselves – but there was no attack. Finally, on 8 November, the Khan withdrew his army. Within three months, he would be killed in a skirmish with a rival horde.

The Russians remember this event as the day on which they finally became free of the Mongol yoke, and, from this point on, the Russians would advance and the hordes would retreat.

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend