This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

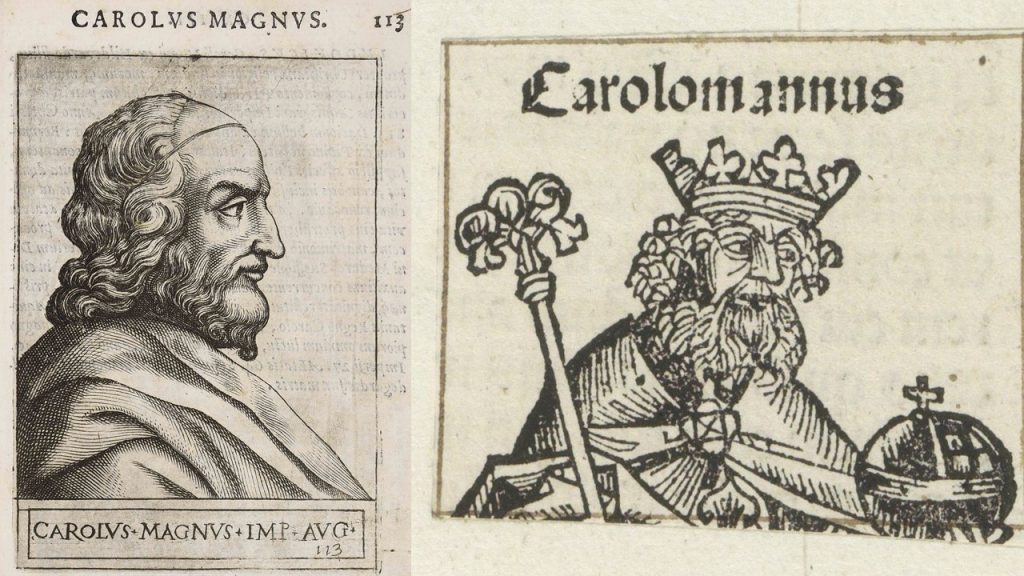

9th October 768 – Carloman I and Charlemagne are crowned kings of the Franks

In the 700s, the Europe we know today would hardly have been imaginable to the people living there.

Europe was still dealing in various ways with the aftermath of the collapse of the Western Roman Empire during the 450s and the Eastern Roman attempts at re-conquest in the early 500s – not to mention the tide of Islamic conquest that had swept over much of the world in the previous century.

The Iberian Peninsula was dominated by the Islamic Umayyad Caliphate, bar the small Christian Kingdom of Asturias in the northern mountains. The Italian Peninsula was split between Arab invaders in the far south and remnants of Eastern Roman control. Most of the Italian peninsular was controlled by a Germanic warrior people called the Lombards, who had invaded in the 500s.

The British Isles were divided into many small kingdoms squabbling for influence, with Britons in the west, Picts and Scotti in the north and Anglo-Saxons in the fertile regions of lower Britain. Eastern and northern Europe were controlled by a sea of Germanic and Slavic tribes about whom little is known by modern historians, as they left no written record.

Life in some parts of the former Roman Empire – such as Italy and southern France – had remained for a time much the same, with church officials taking over the roles of imperial bureaucrats and the new Germanic warlords replacing the Roman army and emperors. However, starting in the disastrous 6th century, which saw a massive outbreak of bubonic plague and widespread war, trade and prosperity began to massively decline, along with literary and cultural activity. The disruption caused by the expansion of the Islamic empires in the 7th and 8th century accelerated these trends.

In other parts of the former Roman Empire, or on its fringes, the collapse of imperial authority led to devastating power vacuums that quickly destroyed wealth and trade and greatly reduced the complexity of society.

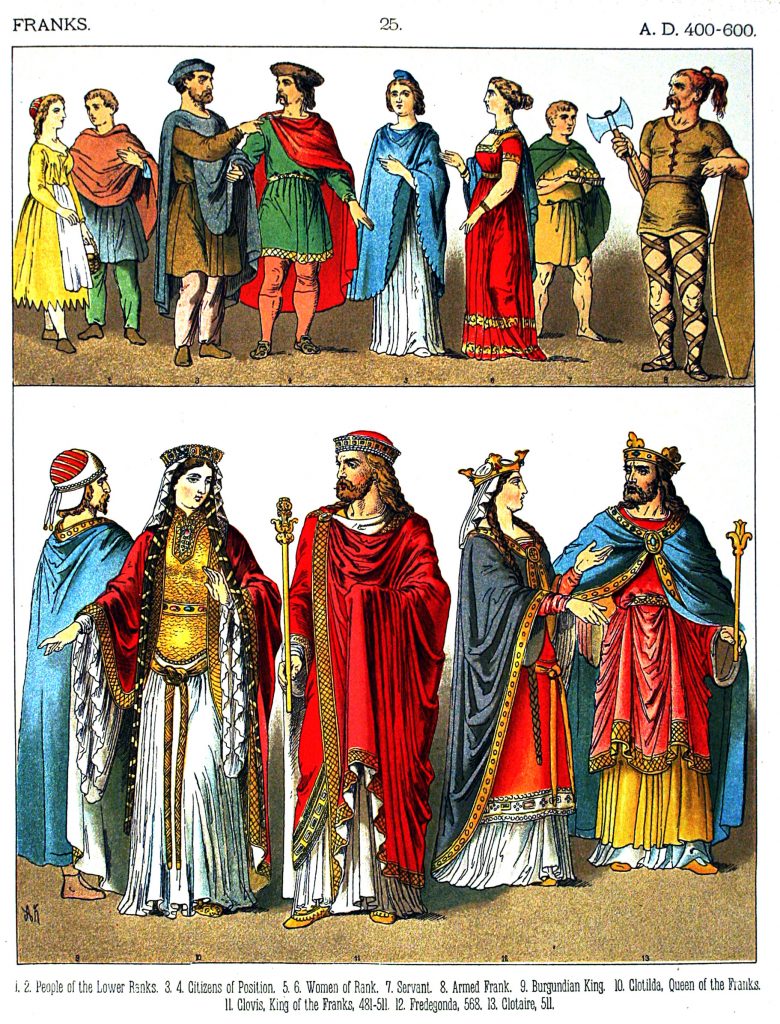

At the dawn of the 8th century, the people of Europe were becoming ever more tied to their settled localities, long-distance trade was greatly diminished, the Christian church was growing in power, monasteries were appearing all across the Christian world, farmers were increasingly tied to the land, and the cultures, languages and customs of the Roman and Germanic people were merging together. However, the world of the Middle Ages, as we popularly imagine it, with knights on horseback, a supreme pope and a landscape dotted with castles, had not yet appeared.

The great power of Europe during the 8th and 7th centuries, dominating modern Germany and France and at the centre of this transformation, was the kingdom of the Franks. The Franks were a Germanic tribe who were the winners of the aftermath of Rome’s collapse. Having allied themselves closely with the Romans in the later empire, the Romans had simply handed over much of the northern Rhine frontier to them. Later, as the central authority of the Romans collapsed, local Roman elites and churchmen simply made deals with the Franks to take the place of the imperial army as their overlords.

The Franks, first under the Merovingian dynasty and now the Carolingian dynasty, had thrown the Visigoths out of southern France, conquered Germany up to the Wesser River, and defeated the invading Islamic armies at the Battle of Tours in 738.

The Frankish king in the mid-700s, Peppin the Short, had grown the ties between the Frankish kings and the pope in Rome, who at this point had not solidified all the powers the papacy today enjoys.

When Peppin died in in 768, his kingdom, as was the Frankish tradition, was divided between his two sons, Charles and Carloman. Charles was somewhere in his 20s at the time and Carloman was around 17. The two brothers quickly fell out, competing for influence and depending on their mother to mediate their disputes. Shared rule of the kingdom did not last long, however; in 771, at the age of 20, Carloman died. While his death is often claimed to have resulted from a severe nosebleed, historians across the ages have speculated that he was murdered. The truth will likely never be known.

In 772, the pope was attacked by the king of the Lombards in Italy, which led to his approaching the court of Charles for aid and protection. Charles complied, leading an army over the Alps into Italy and smashing every Lombard army raised against him. He soon established full control over the northern half of Italy and ended the kingdom of the Lombards forever.

In the following decades, Charles carried out various campaigns of conquest, invading Iberia and capturing land from the Muslim lords there, marching into Saxony and defeating the pagan Germans who lived there (ultimately resulting in their conversion to Christianity), forcing Bavaria to submit to his power, and fighting the nomadic Avar Khanate who lived in modern Hungary, so weakening them that the door would be opened to the later Hungarian migration.

In 799, the pope, seeking to reward him but also influence control over him, crowned Charles as Emperor of the Romans, declaring him the heir of the Roman Empire in the west. This was an honour Charles later came to regret – his biographer and friend, Einhart, claimed the pope had crowned him without his permission.

During his reign, Charles employed many scholars and priests in his court and encouraged culture, which resulted in an increase of literature, writing, the arts, architecture, jurisprudence, liturgical reforms, and scriptural studies, today known as the Carolingian Renaissance, and regarded as one of the first great flowerings of medieval European culture.

While Charles did attempt to learn to read and write later in life, he struggled enormously and even sympathetic biographers who knew him agree that he never really mastered the art of literacy.

When he died in 814, his kingdom would pass to his one surviving legitimate son, Louis the Pious. Louis would have an unhappy reign and would see his sons fight for their inheritance. Eventually, at Louis death, the great empire of Charles would be split into three kingdoms, the western half of which would become France and the eastern half, Germany. This is why Charles is sometimes credited as the grandfather of western Europe.

During his life, Charles came increasingly to be known as Charles the Great, or, as we usually refer to him today, Charlemagne.

10th October 1928 – Chiang Kai-shek becomes Chairman of the Republic of China

-774x1024.jpg)

Chiang Kai-shek was born on 31 October 1887 to a wealthy family of salt merchants in Fenghua, Qing China. When his father died, the still young Chiang came to believe that he was the future of his family’s good name and as such needed to work hard to honour it.

When, in 1906, he was sent to Japan to be educated in military matters, he shocked the people of his hometown by cutting of his queue (a plait of hair worn like a pigtail) and sending it home by post. (You can read more about queues here.)

In 1907, while studying at the Tokyo Shinbu Gakko, he came into contact with anti-Qing revolutionaries who wanted to overthrow the Qing dynasty, which they believed had failed China during the previous ‘century of humiliation’. A year later, Chiang joined the Tongmenghui, a secret revolutionary society aiming to overthrow the Qing.

When the Xinhai Revolution broke out against the Qing in 1911, Chiang, having return to China, fought as an artillery officer on the side of the revolutionaries, leading a regiment in Shanghai. The revolution succeeded in toppling the old regime; in 1919, Chiang became a founding member of the Kuomintang, the Chinese Nationalist Party or KMT.

Chiang soon began working for the leader of the KMT, Sun Yat-sen, who sought to unify China, which had fallen into chaos after the overthrow of the monarchy. In 1924, Sun appointed Chiang to lead the Whampoa Military Academy, which was to train the officers of China’s future armies. Soon after, Chiang resigned from the post due to his opposition to Sun’s close cooperation with the communists, but was eventually convinced by Sun to return. While leading the academy, Chiang built a loyal support base of young officers.

((Sun Yat-sen and Chiang at the 1924 opening ceremonies for the Soviet-funded Whampoa Military Academy

When Sun Yat-sen died in 1925 with no clear successor, a power vacuum opened in China, leading to a struggle for power between Wang Jingwei, Liao Zhongkai, and Hu Hanmin. After Liao was assassinated, and Hu was arrested in connection with the assassination, it seemed that Wang would assume power of the KMT and China. Wang represented the left of the KMT, leaning towards the communists, but the anti-communist Chaing balked at letting him take power and so launched a coup against Wang.

The Soviets decided not to support the communists, fearing it would reduce their influence over China, and so ordered officers loyal to the communists to cooperate with Chiang. Chiang soon reduced the influence of the communists over the army and, in 1926, was named commander-in-chief of the National Revolutionary Army. In the next year he launched an expedition into northern China to bring the warlords, who had ruled the area since the revolution, back under central control.

In the same year, Chaing launched a violent campaign of terror against the communists across China, especially in the cities, and killed an estimated 300 000 people; many of the communists fled to the countryside where the KMT had less control.

His anti-communist suppression and his northern campaign having reinforced his control over China, Chaing began solidifying his status as Sun Yat-sen’s successor and heir of the father of China. Finally, on 10 October 1928, he was appointed Chairman of the National Government of the Republic of China – the first of many times he would hold the highest position in the government of the Republic of China. It was around this time that Chiang converted to Christianity. This was originally thought to have been a mostly political decision to bring himself closer to Sun Yat-sen’s family, but the later discovery of his personal writings suggests it may have been more sincere.

According to Sun Yat-sen’s plans, the KMT was to rebuild China in three steps: military rule, political tutelage, and constitutional rule. The ultimate goal of the KMT revolution was democracy, which was not considered to be feasible in China’s chaotic state. Since the KMT had completed the first step of revolution through seizure of power in 1911, Chiang’s rule was advertised as beginning a period of what his party called ‘political tutelage’. During this so-called Republican Era, many features of a modern, functional Chinese state emerged and developed.

Despite Chiang’s best efforts, however, much of China remained under the control of warlords, and there was widespread banditry during this period as a result. China was also poorly governed and there was enormous corruption across the KMT, which helped contribute to gross mismanagement and famine during the next decade.

Chiang tried to hold China together while simultaneously attempting to modernise its state and legal system. However, he was constantly beset by resistance from warlords and the communists and was almost permanently at war.

The situation worsened in 1931 when Japan invaded northern China and took control of Manchuria. The KMT was too weak to resist them and handed the region over to the Japanese without much resistance. Chiang believed the communists were the greater threat and pursued an unpopular policy of ‘first internal pacification, then external resistance’. In 1934, Chiang’s army almost entirely surrounded and nearly wiped out the communist army, which nevertheless managed to escape in a retreat known as ‘The Long March’, and established themselves in northern China.

In 1937, the Japanese launched a massive invasion of China, seeking to conquer the entire country and bring it into Japan’s orbit as a puppet state. Chiang’s army was poorly equipped and trained compared to the Japanese, and fought desperately to stop the invaders. In a desperate move in 1938, the Chinese opened the Yellow River dikes, flooding a huge area of the country in an attempt to stop the Japanese. Some estimates believe this flood caused the death of 800 000 Chinese civilians.

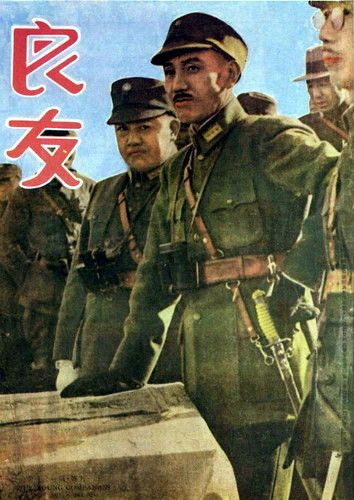

((After the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War, The Young Companion featured Chiang on its cover.

During the Second World War, the Japanese army’s advance was slowed by the combined resistance of the KMT and the communists, with Chiang’s army being supported by Britain and America, which helped supply and train the nationalist forces.

However, the war sapped the strength of the nationalists and the Japanese destroyed many nationalist army units during fighting; despite being on the winning side, the KMT was broken. At the end of hostilities in 1945, the KMT and the communists resumed their civil war. With some Soviet aid, the communists smashed Chiang’s army in 1949.

Chiang retreated with large numbers of refuges to the island of Taiwan, where the government of the Republic of China established itself. The communists lacked the naval resources to follow him and so Taiwan remained under his control. While Chiang dreamed of one day retaking the mainland, he was never able to do so, and he remained the dictator of Taiwan until his death in 1975.

After his entombment in a mausoleum in Taiwan, Chiang’s his successors in Taiwan would slowly loosen the authoritarian controls he created. Today, Taiwan is a free nation which provides a vision for the world of what China could be without authoritarian rule, and is considered a great threat by the Chinese Communist Party.

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend