Can you tell how rich or poor someone is by looking at their skin in South Africa? Apartheid aimed to make it so. In 2020, has anything changed – in fact or in perception?

Many people believe that race is a proxy for poverty in South Africa today. David Masondo, former president of the Youth Communist League and current Deputy Minister of Finance, recently wrote in the Daily Maverick that “[d]ue to its colonial legacy, colour remains a proxy for inequality, poverty and unemployment in today’s South Africa”.

In September Steven Grootes wrote that “the simple fact is that the majority of South Africans believe that race indeed is a proxy for disadvantage. They believe, with firm evidence, as well as their lived experience, that white people are rich and poor people are black.”

And Thamsanqa Malusi, a lawyer with a Seattle-based law firm, wrote that as “beneficiaries of centuries’ long exploitation of black, coloured and Indian people, whites remain far more privileged in South Africa by comparison”.

And yet if you look at the Stats SA data that Grootes hyperlinks, in particular its Inequality Trends report, a different picture emerges.

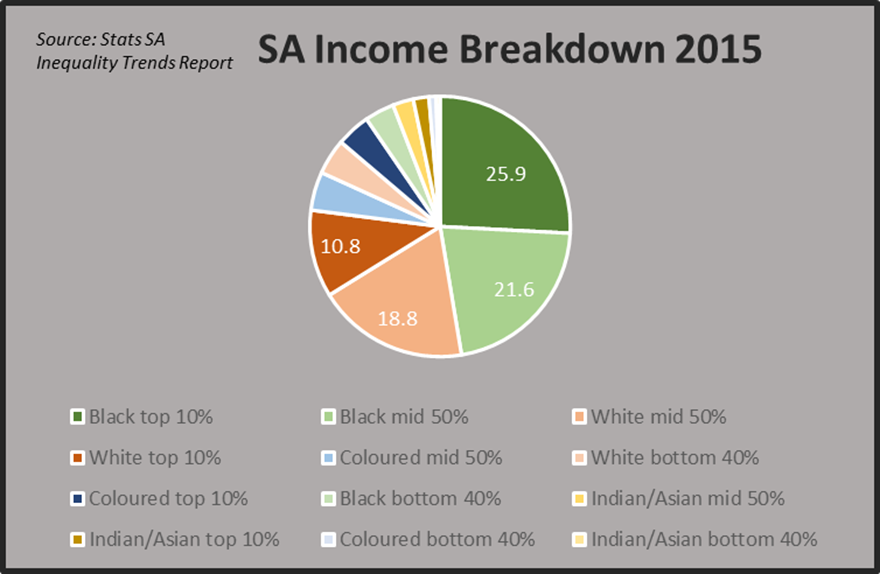

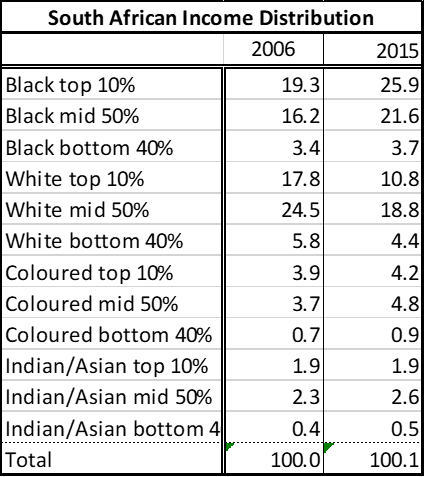

South Africa has extreme income inequality, the top 10% earning more than half of national income. But how does this cut across race? Stats SA shows that in 2006 white South Africans earned almost half of all income, but by 2015 this was down to 34%.

Getting richer

If black income had increased at a higher pace than increasing white income this would surely have been a good thing, as happened in the mid-2000s. Most people were getting richer, but black people, starting from a lower base, simply outpaced white compatriots in income growth.

Since then, however, the economy effectively halved, compared to the growth path it was on in the 2000s.

By 2015 the black top 10% earned 25% of national income. The white top 10% earned 10%. The black middle 50% earned 21% of national income.

Only within the black category do you see the top 10% earning more in absolute terms than the middle 50%.

Using “black” on the broader BEE definition, the top 10% earned 32% of national income back in 2015. That means the BEE “disadvantaged” elite earned three times more in absolute terms than its white counterpart just at the time when “white monopoly capital” became the bogeyman to blame for all woes.

On the same basis, the number of black dollar millionaires was overtaking white equivalents around 2015, too, according to New World Wealth.

Nevertheless, in 2020 President Cyril Ramaphosa said the economy in which white people earn a third of all income is “colonial and racist” as trillions on the stock market and millions of jobs were shed.

If you think “white people are rich” you might assume no white person was badly affected. Yet over a million white people are now not economically active and over 100 000 are unemployed, according to Stats SA. Even if Grootes cannot see them, these people are not “nobody”.

Moving from data to “lived experience”, I cannot think of a single South African who is still surprised to see a black celebrity wedding, a black person driving a fancy car, sporting Gucci, or flying business class through Dubai. The common response to seeing a white beggar, especially in small towns, is no longer to take a photo or tell a friend. Rich black people and poor white people are not a secret to anyone, except pundits and politicians.

Weirdest lived experience

But the weirdest lived experience must be this. You see someone get out of a sports car, besuited and flash, to come and make a multimillion-rand deal. Her CV is splendid. She has worked with international firms, has connections in government, and boasts of her premium degree. Then BEE compels you to judge her “disadvantaged” and in special need of help because her skin is dark. This, or something like it, is the lived experience of every major deal-maker on West Street in Sandton.

So what, you may ask? Black elites and poor whites do not mean the legacy of apartheid is over. Look at the poorest half of the country; most people in dire straits are black. That is true, too.

According to Stats SA’s report, the black bottom 40% earned 3.7% of national income in 2015. That is seven times less than the black top 10%. Put another way the black elite earned 28 times more, per capita, than the black lower class.

The conventional argument following this observation is that poor black South Africans can only be lifted out of poverty by more legal discrimination on the basis of race. Malusi and Masondo both argue that this is the route forward, without explaining how poor, disaffected, and poorly educated black people are supposed to outcompete the incumbent black elite. Malusi avers that there is no other way and Masondo goes a step further to say, “the state has had to introduce black economic empowerment” to “solve inequalities”.

Statistical discrimination

This is what economists call “statistical discrimination”. When something important is hard to know and something unimportant is easy to know and the two are highly correlated people use one as a proxy for the other. Statistical discrimination can be benign and useful.

For example, sailors who lack high-tech navigation equipment use birds as proxies for land. They know which species have to land every evening so if they see such a bird in the sky they assume there is land nearby even though they cannot see it themselves. This proxy can be lifesaving.

For a low-stake racial example I was looking for someone who could speak English at a train station in Moscow. When I saw a black man, I guessed that he was foreign and so more likely to speak English than the rest. I went up and asked for directions in English; my guess was right, and he helped me find my way. (But not before engaging me in conversation that ended with him saying, “One day you can tell the story about when two Africans met on a train station in Moscow”, and a hug goodbye).

Though it can be useful and benign sometimes, statistical discrimination is pernicious. When police do “race profiling”, that is statistical discrimination where they guess who is antisocial by using race as a proxy for criminality.

BEE is explicitly statistical discrimination that uses race as a proxy for disadvantage. But is it helpful or harmful?

Effectiveness of statistical discrimination

Putting morality to the side, the effectiveness of statistical discrimination is dependent on how closely the known factor is to the unknown factor. If rich, educated, well-connected people were almost all white then race would be an effective proxy for advantage. Yet every time a black person makes a million, gets a degree, or gains the trust of someone in power, that correlation between disadvantage and race reduces.

So the first problem for BEE proponents is that, to whatever extent you think it worked over the last 15 years, it is no longer a useful proxy to exactly the same extent. Conversely, to whatever extent you think BEE is still a useful proxy, it has not worked.

The second, perhaps more surprising problem is that race turns out to be harder to see, from a government perspective, than income and education certification. Race is the invisible land while actual advantage is the visible bird in the sky.

Take the case that prompted Masondo’s and Malusi’s recent articles. Glen Snyman called himself “African” on a job application and was then briefly charged with “fraud”. Perhaps the most mind-boggling thing about the case is that the government not only had to ask Snyman for his race (lacking it on their own database), it also has no way to confirm or disprove his race in law.

Malusi said Snyman’s “official records” prove that he is “coloured” not black, but it is unclear what “official records” he has in mind. To be sure, Snyman was officially categorized by race during apartheid, but then the Population Registration Act was repealed in 1991. As it stands there is no “official” pencil test, DNA test, or method of any kind to prove the dispositive regarding a person’s race.

Access to evidence

By contrast, through the tax system and the social grants system, the government has immediate access to evidence of who earns millions and who hardly gets mealie-pips. Moreover, through the education accreditation system, reliable records can be established of what school and university qualifications you have. The government can in practice and in principle find out your actual, relevant advantages, but cannot begin to prove your race one way or another.

This could be changed by legislating new pencil- or DNA-based tests. But to what end? We already know how to figure out if people are poor and poorly educated and race does not come into it.

If the downtrodden masses in this country are to stand a chance of building wealth it will not be by using pencil tests to figure out if they can afford to buy a goldmine. It will be by using hard evidence to root out the looters; it will be by using the hard edge of law to break the crony cartels; and by judging one another as agents of change or devotees to what Justice Edwin Cameron called “more same, more same”. Nothing could be more “more same” than judging a South African’s need by the colour of her skin.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend