This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

22nd November 1995 – Toy Story is released as the first feature-length film created entirely by computer-generated imagery

In 1982, the science fiction film Tron showed the world that the age of the computer was just around the corner. While the film was a mild disappointment financially, it demonstrated what could be accomplished with computer-generated graphics. John Lasseter, an animator at the Disney corporation, saw Tron and immediately recognised that a new type of film would be possible; he later identified this as the moment that inspired him to begin thinking about how to make an entirely computer-generated animated film.

A few years after watching Tron, Lasseter joined George Lucas’ company, Lucasfilm, and from there went on to become a founding member of the new computer animation company, Pixar, which was then purchased by Apple founder Steve Jobs in 1986.

In 1988, Lasseter and his company produced a short film called Tin Toy, a computer-generated animated film which won the 1988 Academy Award for best animated short film, the first computer-generated short film to do so.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s Pixar reached an agreement with Disney to produce a full-length feature film using only computer animation, the first of its kind. The film would come to be known as Toy Story. Between 1991 and 1993, Pixar worked on the film and frequently clashed with Disney executives, some of whom were uncomfortable with an outside studio producing a film for Disney. This reached a climax in November 1993 when an early draft of the film was heavily criticised for its writing by everyone who saw it. This led to some at Disney calling for the project to be cancelled, forcing a rework of the script.

In February 1994, the film and its new script re-entered production. The production crew on the project grew from around 24 to 110 during the production process and its budget would end up being around $30 million. This was in contrast to Disney’s flagship project of the time, 1994’s The Lion King, an animated film which needed a budget of $40 million and a staff of 800.

Due to their unfamiliarity with editing and putting together a computer animated film, many on the cast were worried that the film was in poor shape, with some fearing it would be a box office disaster, attracting only people who were interested in and familiar with computer animation. As time went on, however, Steve Jobs and Disney executives became increasingly impressed by the quality of the work and believed they were about to change movies and animation forever.

On 22 November 1995, Toy Story was finally released to the public, and received immediate critical acclaim. Today, the film holds a 100% Fresh rating on the film review aggregator website, Rotten Tomatoes. At its release, the film was praised not just for its innovation but also for its voice-acting performances and its heart-warming story. With $30 million spent on production and another $20 million spent on advertising, the box office return of $404.8 million netted a healthy profit for Pixar and Disney.

Pixar would go on to become a giant in the animation industry, and still produces many hit films using computer animation. The success of Toy Story would indeed revolutionise the industry; the film was followed not only by more computer-animated films, but the increasing use of computer graphics in real-life films.

23rd November 1248 – Conquest of Seville by Christian troops under King Ferdinand III of Castile

In the year 711, Muslim troops of the Umayyad Caliphate led by Tariq ibn Ziyad landed at Gibraltar on the southern coast of what is today Spain. Over the next few decades, the Islamic armies pushed north across the Iberian Peninsula until, by 726, they had taken most of the peninsular by conquest from the Christian Visigothic kingdom which once ruled most of the region.

The one exception was a small Christian kingdom in the north called Asturias, which clung on in the mountains of northern Iberia. The Islamic armies continued over the Pyrenees into southern France, where they were eventually defeated and pushed back by the Franks at the battle of Tours in 732.

During this period of Islamic dominance there was an extensive cultural exchange – of goods, culture, and language – between the Christian and Muslim inhabitants of Iberia. The Islamic kingdoms of southern Iberia became known for their splendour and architectural marvels. The centre of Islamic rule and culture in Iberia was the city of Córdoba.

Over the next few centuries, accelerating in the 11th century, the Muslim powers began to fragment while the Christian powers consolidated around the three major kingdoms of Portugal, Castile, and Aragon. Over the next few decades, Castile in particular, became the dominant Christian kingdom and began pushing the Islamic powers back. A long struggle followed, known to historians as the Reconquista, the Reconquest. This was not a straightforward process of inevitable Muslim defeat at the hands of Christians; it was much messier. Muslims and Christians allied with each other occasionally, Christians fought Christians, Muslims fought Muslims, and occasionally the Muslims regained ground, such as when the Berbers of the Almoravid Sultanate crossed from North Africa into southern Iberia and pushed back the Castilian armies.

However, as time passed, clear trends began to emerge. In the 11th century the Castilians captured the city of Toledo, near modern Madrid in central Spain. In the 12th century the Portuguese kingdom was established when the Almoravids were defeated when a Christian count amassed a large army and declared himself king. In 1236 the Christians shocked the Islamic world when a Castilian army rapidly captured Córdoba and broke the back of Islamic power and influence in Iberia.

In the mid-13th century, the Castilians launched several attacks on the major Muslim cities of southern Spain. In the summer of 1247, a large Castilian army laid siege to the city of Seville, the most important Islamic city in the region after Cordoba.

The siege was hard fought and lasted 16 months. It included a naval blockade and is the first recorded action of a Spanish navy. Eventually on 28 November 1248, the city, which was starving, surrendered to the Castilian army. The only Muslim city which remained in Iberia was the powerful fortress of Granada, which would remain mostly independent until 1492 when the joint armies of Castile and Aragon captured the city and expelled the Muslims from Iberia.

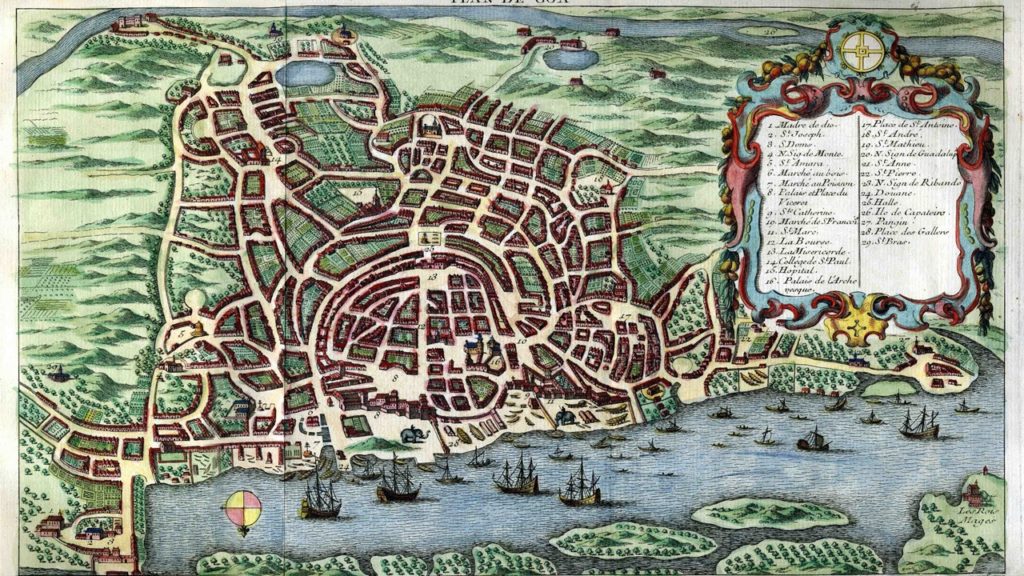

25th November 1510 – Conquest of Goa: the beginning of 451 years of Portuguese colonial rule

Within a few years of the return from India of Portuguese explorer Vasco De Gama, the Portuguese crown began to take a great interest in the newly discovered route between India and Europe via the Cape of Good Hope in Africa.

Portugal was very poor compared to most European kingdoms and its king hoped to make the kingdom richer by expanding trade in Africa and to taking control of the spice trade originating in India. Until then, the spice trade had been dominated by collaboration between the Muslim powers controlling Egypt and the Italian city states of Genoa and Venice.

To this end, the Portuguese crown began outfitting military expeditions which were sent into the Indian Ocean world to displace Muslim power in the region and establish Portuguese control of the trade routes there.

In 1509, the Portuguese sent a new governor to its operations in the Indian Ocean. Afonso de Albuquerque realised that the key to establishing Portuguese dominance in the region was the capture of key Indian Ocean port cities – Aden in Southern Arabia, Hormuz in the Persian Gulf, and Malacca in modern Malaysia.

Until this point, the Portuguese had mostly operated from bases in the territory of local allies who shared common enemies in the Islamic powers. The Portuguese recognised, however, that this left them vulnerable to being ejected by their allies, who were often fickle. To that end, Afonso decided that establishing a directly controlled enclave in India would greatly strengthen their operations in the region.

The Portuguese identified the Indian city of Goa as a prime spot for their conquest, as it had a mostly Hindu population who were resentful at being ruled by the Islamic Bijapur Sultanate, the Muslims having conquered the city in 1496. The Portuguese were able to identify this weakness, as they had made an alliance with an Indian pirate lord called Timoji who fed them information and who worked for the Hindu Vijayanagara Empire, an enemy of Bijapur. (The Vijayanagara Empire was covered in This Week in History earlier this year.)

On 17 February 1510, Portuguese forces occupied Goa without resistance. The city surrendered to the invaders as they promised lower taxes and religious freedom for citizens. The Portuguese immediately appointed their pirate ally,Timoji, as the chief tax collector of Goa and representative of the city’s Hindu population.

Unknown to the Portuguese, however, Bijarpur had just signed a peace agreement with the Vijayanagara Empire, which immediately dispatched a huge army of 40 000 troops to eject them. The Portuguese were soon besieged within Goa by the Bijapur army. The onset of the monsoon rains – which brought disease and rotted their food supplies – caused the Portuguese much suffering. A revolt broke out against them, but was crushed. The Portuguese and their Hindu allies slaughtered the Muslim inhabitants of the city in retaliation and abandoned the city.

The monsoons, however, continued to hamper the Portuguese, the heavy rain and high seas trapping their ships in the river near to Goa. Finally, after a difficult period of near starvation – and a mutiny – they managed to escape and retreated to a nearby allied Indian city. Later that year, they were reinforced by more Portuguese ships.

In November, the Portuguese forces returned to Goa and attacked the city. While they succeeded in capturing Goa from Bijapur on 25 November 1510, a fort occupied by Muslim troops remained near the city. The Portuguese rebuilt the city’s defences and a stalemate ensued.

In 1512, with the city now well defended and reinforced with more Portuguese troops, an assault was launched on Muslim fort, which was eventually captured, thus securing the city for the Portuguese crown.

The Portuguese applied in Goa practices that had governed much of their rule of Muslims back in Iberia – allowing religious communities to live under their own laws so long as they paid tax, and allowing each religious community to be represented by a member of their community to the royal officials. The Portuguese did, however, abolish the Hindu practice of Sati (widow suicide on the death of a husband).

The city became the centre of the Portuguese Empire in the east and would govern the empire’s interests in Middle East, Indonesia and Mozambique. The Portuguese would rule Goa as part of their empire until 1961 when the Indian army attacked the Portuguese territory, taking the city back into Indian hands after a 36-hour battle.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend