This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

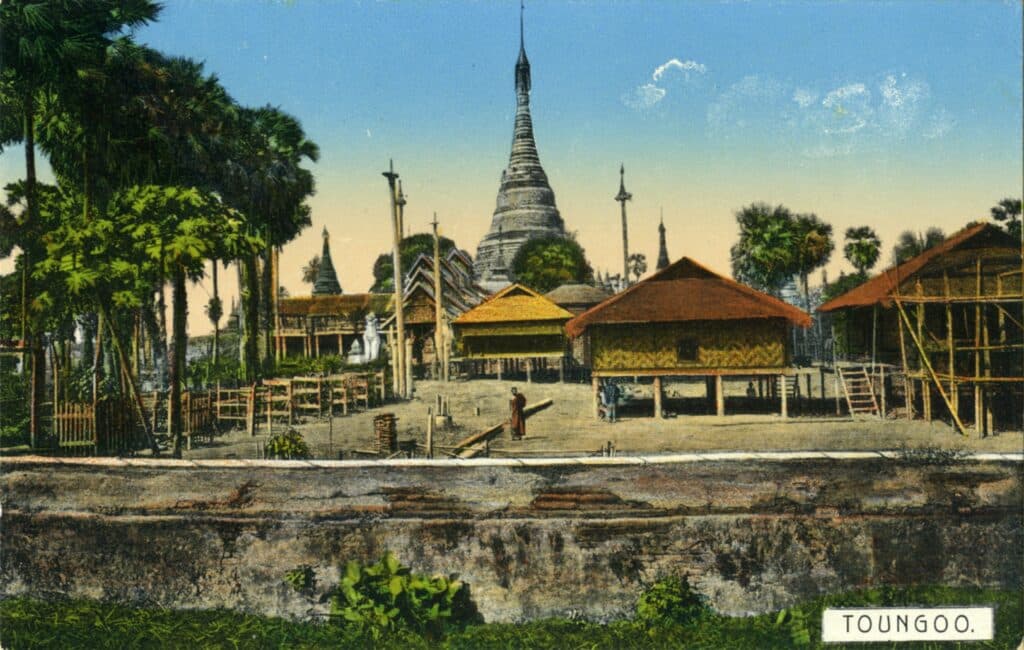

22nd January 1555 – Kingdom of Ava in Central Burma falls to the Taungoo Dynasty

For much of the late medieval and early modern period, modern-day Myanmar (Burma) was ruled by warring kingdoms and cities who vied for dominance. In these turbulent times empires rose and fell with great drama and violence.

One such mighty empire was the Kingdom of Ava, founded in 1364 by the great king Thado Minbya. Ava was founded by the union of two earlier kingdoms in central Burma, which had become weak due to raids by the fierce warrior people to the north called the Shan.

Thado Minbya was once a vassal of one of the preceding kingdoms but, after a particularly brutal raid by the Shan, he and many other vassals declared their independence. He built his kingdom by fortifying it with great citadels, storing food for long sieges, as well as through bravado and military skill, which allowed him to conquer the cities of Burma and hold off the Shan raiders.

In three years he unified all of central Burma and declared the Kingdom of Ava, with its capital in the city of Ava. He was only 21 years old. In 1367, however, he died of smallpox while on a military campaign, and the kingdom passed to his brother.

The kings of Ava who followed tried to restore the ancient pagan kingdom which had ruled the region in centuries past by bringing all the Shan, Burmese and Mon people under their banner. To do this, the Ava waged wars against their neighbour to the south, the Mon kingdom of Hanthawaddy, which ruled the coastal region of modern-day central-southern Myanmar.

The height of these conflicts between Ava and Hanthawaddy was the series of conflicts known to history as the Forty Years War between 1385 and 1424, when the two kingdoms battled for supremacy. Hordes of clashing soldiers and war elephants battled across the region in numerous campaigns that lasted decades. In the end the Ava secured tribute from some of the northern Shan kings who had aided the Hanthawaddy, but almost no territory changed hands and both kingdoms were left exhausted and weak.

Between the 1420s and 1480s, the Ava faced recurring rebellions from their vassals every time a new king came to the throne, and after six decades of this the kingdom finally began to collapse in the 1480s when the city of Prome broke away to form its own kingdom and the Shan, who had paid tribute to Ava, revolted too.

From the 1480s to 1510, the Ava vassal city of Taungoo grew in power and soon eclipsed their old overlord, declaring independence in 1510. The situation grew worse in 1527 when the Shan kings formed a new confederation and began raiding Ava again. In 1542 the Taungoo captured the city of Prome and on 22 January 1555 the city of Ava was finally captured by the mighty King Bayinnaung of Taungoo, ending its time as a major city in the region.

The Taungoo king, Bayinnaung, would go on to conquer what is considered South East Asia’s largest empire in history, stretching from modern-day eastern India to Myanmar, Thailand, Laos and Cambodia.

25th to 28th January 1077 – The March to Canossa

In the 11th century, the most powerful ruler in Europe was the Holy Roman Emperor, a man who ruled an empire founded in the aftermath of Charlemagne’s empire, which encompassed much of modern-day Germany, eastern France, Belgium, the Netherlands and northern Italy.

These emperors claimed to be heirs of the Western Roman Empire and the anointed secular leader of all Christians on earth, the right hand of Christ and the defenders of the Christian world. In reality the Holy Roman Emperors were German kings who struggled to hold on to a patchwork of cities and kingdoms ruled by numerous rebellious vassals. The emperors managed to control much of their territory by appointing bishops to manage sections of the country. As bishops could not have legitimate children and owed their appointment to the Emperor, they were easier to control than dukes or counts, who were prone to prioritise their own families over the Emperor.

While initially this system worked well, there was a wrinkle. The popes of the 11th century were ambitious, and most had begun to embark on a period of strengthening their control over the Catholic Church, which in the early Middle Ages had been quite decentralized. The Popes were appalled by what they saw as corruption of the church by politics and believed that the pope and the church should have full control over who was appointed to bishoprics across the Christian world. This of course would undermine the ability of the Holy Roman Emperors to rule their realm effectively and would make them subject to the whims of the pope.

So began the investiture crisis, as it is known to historians, a period of conflict between emperors and popes over who was the foremost leader of the Christian world. While the emperors had great military strength and prestige on their side, the popes had cunning, and diplomatic power.

Things came to a head in the 1070s between Emperor Henry IV and Pope Gregory VII. Henry had just put down a rebellion of some of his vassals in the German province of Saxony when he decided to appoint a new bishop to the bishopric of Milan. The man he chose was not the Pope Gregory’s choice and this outraged the pontiff, who decided to punish Henry by declaring him excommunicated and all oaths sworn to him by his vassals null and void.

The Emperor responded by getting the bishops loyal to him to elect a new pope (usually called an anti-Pope). This new Pope found little acceptance and the rebellious Saxons used the excommunication as an excuse to renew their rebellion against the emperor.

The rebellion gained strength and soon Henry was in trouble. He realised that the only way to escape the crisis was to be forgiven by Pope Gregory, at least until he was stronger.

So, in order to be readmitted to the Church, Henry marched to the fortress of Canossa in the Alps of norther Italy, where the Pope was staying at the time. Henry arrived at the gates of the fort on 25 January 1077, wearing an itchy hair shirt and bare feet in the snow.

The Pope refused him entry and for three days he knelt in the snow at the gates of the fort praying and doing penance. In the end, the Pope opened the gates on 28 January and readmitted Henry to the Church.

This was not the end of the investiture crisis; soon the Pope would excommunicate Henry again, but it was a powerful moment for the history of Germany and the Church and would take on significant symbolic meaning in years to come, being adopted by early protestants as a symbol of the tyranny of the church and, by German nationalists, as a moment of national humiliation.

What it revealed to contemporaries, however, was that the Pope was not to be trifled with.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend