‘Citizen abuse’ is what happens when a government acts against the best interests of its people. It is a pervasive condition in South Africa in 2021 – and poses the risk, for the ruling party, of triggering a tax revolt, the effect of which could be to bring down the government. These key points are contained in a memorandum the Institute of Race Relations (IRR) delivered to the Presidency yesterday. Here is the full text of the memorandum.

Citizen abuse in South Africa and the threat of a tax boycott

Introduction

The budget speech revealed that the finances of the government are collapsing under the weight of its policies and their contradictions. At the same time, officials of the government and some activists are lobbying to increase taxes, introduce new taxes, and even seize the savings of households to cover state-spending gaps. Ordinary South Africans are thereby being forced to pay for the counterproductive policies, management failures, corruption, and ineptitude of the government in what could really now begin to be described as a phenomenon of ‘citizen abuse’ by the state.

In this letter we set out the facts around the government’s financial crisis and from there raise the spectre of a tax revolt and investment revolt should the government proceed with tax increases and asset seizures.

What is citizen abuse?

Citizen abuse happens when the state:

- Takes its citizens for granted;

- Steals from taxpayers;

- Wastes resources and money meant for community upliftment;

- Appoints incompetent staff and officials;

- Fails to take action against corruption and incompetence;

- Introduces policies that harm the economy and deny access to economic opportunities;

- Insults or stigmatises some citizens on grounds of race, ethnicity, nationality, gender, socio-economic status, or sexual orientation;

- Undermines the rights and freedoms citizens enjoy;

- Opposes citizens’ efforts to build better communities; and

- Physically abuses citizens by, for example, shooting at them, beating them, torturing them, or confiscating their goods and assets.

How serious is the revenue problem?

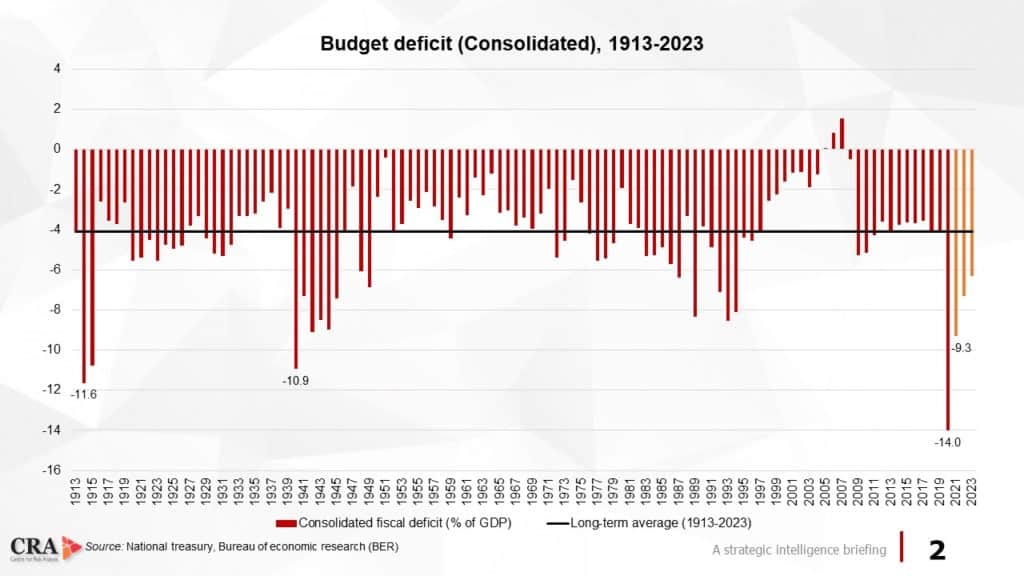

Chart 1 sets out South Africa’s budget deficit since 1913 and suggests to us that the financial position of the government, when read against its growth prospects, has become unsustainable. For the benefit of the broader readership of this memorandum, the deficit measures the difference between what the government spends and what it earns from taxes and other sources. Financing the deficit requires that the government borrow money – which is fine if government is confident that its future rate of economic growth will be sufficient to pay back what it has borrowed.

However, in South Africa’s case, the deficit is a multiple of the rate of economic growth and debt levels are therefore escalating faster than the economy is expanding. To put that in plain language: we estimate that the government will soon be borrowing R1 of every R4 that it spends and that it is already the case that R1 of every R5 earned in revenue by the government goes to paying the interest on the money it has borrowed. The position is so serious now that, as Chart 1 shows, the deficit today rivals levels recorded only three times in South Africa’s history: during the two World Wars, and in the late 1980s when, under the leadership of PW Botha, the apartheid economy collapsed under the weight of its own contradictions.

What is the government planning to do about running out of money?

Our take from their policy documents, comments, and actions is that both the government and the ANC are pursuing a strategy to do the following:

1. increase existing taxes;

2. introduce new taxes;

3. borrow more; and

4. employ the savings and pension funds of ordinary citizens in order to prop up the government, finance parastatals, pay wages, and maintain the cashflow to cadre deployment networks.

Later, as these resources become exhausted, we fear that factions within the government and the Cabinet will turn to the printing of money.

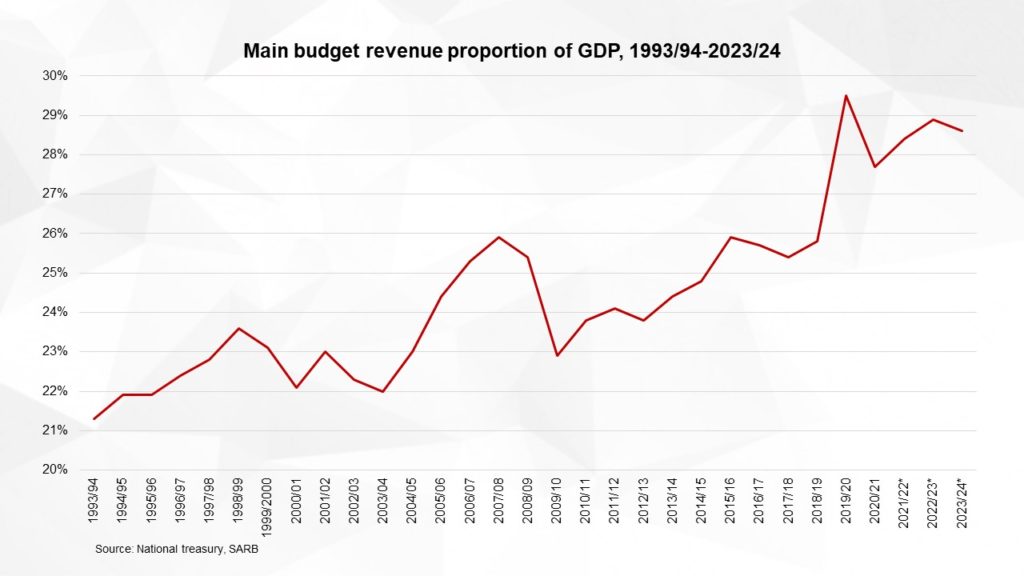

Chart 2 (below) represents a smoking gun of sorts. The chart measures how much tax the government takes from South Africans and investors as a share of the size of the economy or GDP. That figure has increased by over 30% since 1994, from around 21% in 1994 of GDP to approaching 30% of GDP today.

No previous South African government has taken more from its citizens and investors – pre- or post-1994. Add increases in administered prices such as electricity price hikes and toll roads – which are all a form of taxation – and the burden is even greater than the narrow tax data suggests. In part because this rising burden, research into household spending reveals frightening insights into how many families now struggle to pay the bonds on their homes or even their children’s school fees. For entrepreneurs, investors, and employers the burden is even greater given the regulatory, licensing, BEE, and compliance fees they are expected to pay, which all amount to a form of taxation. Even the poor (who are in the main indirectly affected by tax increases when firms cut investment or jobs) became direct victims of the government’s taxation policies when it made the decision to increase the VAT rate by 7%.

That injury is then compounded by insult. It is not uncommon to hear complaints that investors are here only to profiteer, with their broader contribution to jobs, capital formation, and exports being dismissed. The middle classes are often decried as a greedy elite who do nothing for the poor and little to build a better society, for which they are then threatened with new wealth taxes (when South Africa already has significant wealth taxes), prescribed assets, and expropriation without compensation.

Specific contempt is shown (by people who still sit in the government) for ‘clever blacks’ – a community which in addition to the taxes they pay to the government carries the responsibility of sharing what is left after tax with older generations and the great numbers of unemployed black people. Not even the poor are spared the government’s contempt, as was seen when water cannons were turned on desperate people queuing for social grants in January 2021.

You can see why we coin the phrase ‘citizen abuse’.

Why is the government running out of money?

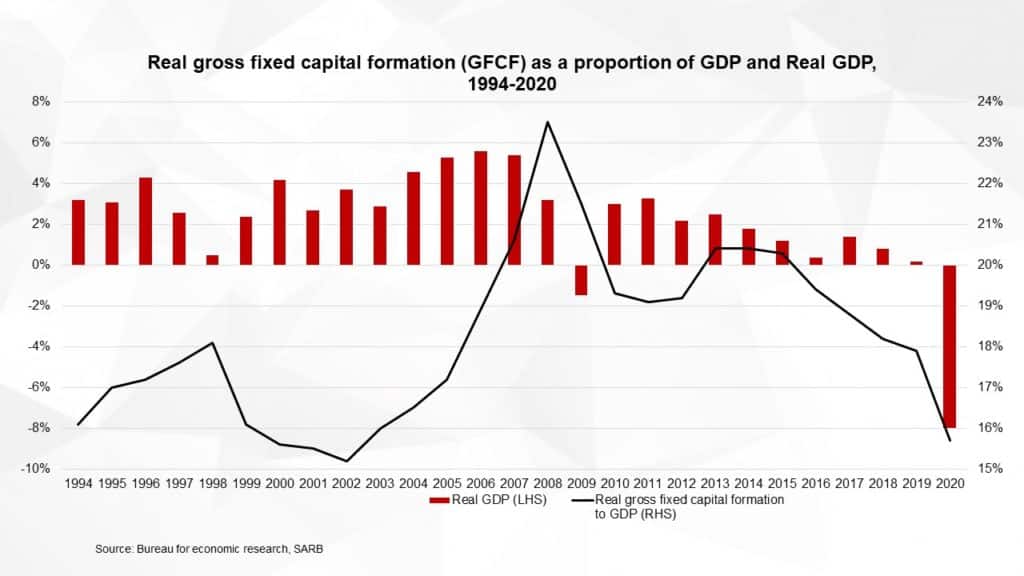

The reason the government has moved to increase the burden on taxpayers is that it is attracting too little investment to grow the economy at a rate fast enough to stabilize the deficit and its debt levels. Chart 3 sets out the evidence. It tracks fixed investment levels into South Africa as a share of the size of the economy over the past two decades. What it shows is that investment levels have plummeted since 2008 and are still falling.

The reasons for this include above all else the threat of expropriation without compensation, which was first explicitly voiced in late 2007 before being translated into draft policies and laws. These laws are currently making their way through Parliament and would allow the government to seize without compensation any fixed or movable asset invested in South Africa. That would include farmland as well as the livestock and equipment on South Africa’s commercial farms. But the threat extends far beyond that, as the law would allow the government via expropriation or custodial takings to seize savings, pensions, shareholdings in companies, intellectual property, homes, cars, bank accounts and any other asset. This might not be well understood by ordinary people or the local media, but it is very well understood by the investors, entrepreneurs, and employers that South Africa needs if it is to stage an economic recovery.

Secondary reasons range from corruption – which continues to run rampant across every sphere of the government – to plain government incompetence. Incompetence is demonstrated for instance in municipalities being so ineffectual that they cannot fulfil functions as basic as providing clean water to their residents, and extends all the way to the overarching burdens of everything from BEE compliance to running a business under circumstances of unreliable and increasingly expensive electricity. On the corruption score alone, we estimate that a majority of the present senior leaders of the ANC have been publicly implicated in allegations of serious corruption.

How will South Africans respond to the above?

Many who have the means to do so leave the country. Privately, the Treasury recently bemoaned that each high net worth individual who exits South Africa costs the government a very great sum in lost tax revenue annually as well as taking the jobs they create and the salaries they pay to other countries.

Among those who remain, the abuse they face at the hands of the state causes them to lose further confidence in the government and they turn away from it and look instead to relying on their own efforts to build safe and prosperous communities. This phenomenon is reflected in polling that reveals the extent to which confidence in the government has diminished, with our latest numbers revealing that support for the ANC has now fallen below 50% among well-educated people, people in employment, and people in higher income categories, while ANC support among the poorest South Africans is well below the levels recorded in the first decade after 1994.

Diminishing confidence in the government, as your best tax advisors have already advised, translates directly into lower government revenues. But we don’t think that this is the end game. Rather, we think that further slippage in the legitimacy of the state will see communities begin to engage in a tax and investment revolt which is something the government has not yet experienced on any significant scale.

Our initial thoughts are that this could occur in any one or a combination of the following four approaches – although we must also stress that this list is not exhaustive:

1. The first is for taxpayers and ratepayers simply to circumvent the government by paying their dues into trust accounts or to third parties which then finance private service delivery and community-building efforts, as is starting to happen in many towns around the country. Small communities begin to bypass the government, which is then further starved of revenues.

2. A second is that, on a larger scale, the private sector begins to set up initiatives to address social ills – from crime to service delivery failures, and deficient healthcare and education, among others – that attract donations which are employed to finance delivery efforts via private channels. The tax implications of these donations may have the effect of diverting revenues away from the state. Early models of this, to a greater or lesser extent, are already being trialled.

3. A third is that communities just cut the government out of their lives by, for example, taking it upon themselves to generate their own electricity and finance and build their own schools. They therefore stop paying the state for these services.

4. A fourth is that communities begin to lobby the government for rebates where they have been forced to spend money beyond the taxes and fees they already pay in order to safeguard their communities, educate their children, and access health services. For example, taxpayers could claim tax credits for their investment in installing solar panels to help South Africa address its electricity crisis. Credits could be claimed for private security expenditure which has had the effect of bringing down national crime rates. Credits could also be claimed for expenditure in support of independent schools that have the effect of raising the country’s education profile and hence growth prospects. It would be very difficult for the government to win a public debate on the grounds that such rebates would not be justified, and the case for rebates could gain considerable political steam.

Were this to become the case, it is not clear what good option the government may have to head off the revenue losses. It would be forced, for example, to tax households that go off-grid via solar power or to ban community-driven service delivery programmes. But such actions would result simply in driving remaining taxpayers abroad, leaving the government in an even deeper revenue hole. And in this sense the greater revolt – caused by taxpayers leaving the country in large numbers – is one that the government has already brought about.

What must be done?

To head off these risks, the following needs to be done.

First is to cut out the corruption that still characterizes the government by firing all officials implicated in allegations of serious corruption. Thereafter they can be prosecuted together with their enablers in the private sector. This means sweeping dismissals and prosecutions that would involve literally thousands of people. It has been three years since Mr Zuma vacated office and the public is learning to see through the delays in dismissing corrupt officials and sending them to jail.

Second is to cease all cadre deployment and related policies to ensure that the civil service employs only on merit and with no regard to other considerations. Short of that, confidence in the ability of the state will continue to decline.

Third is to provide the firm assurance – which can only be done by halting the current expropriation drive – that the government will not seize investment capital or the savings and businesses of South Africans. Short of such an assurance, South Africa’s fixed investment-to-GDP figure will not recover substantively and the government will be slowly starved of revenues.

The fourth is to use the savings that would accrue from firing corrupt officials and replacing them with capable people, and the new investment that would become possible if the expropriation threat is removed, to reduce the tax and revenue burden on South Africans while improving the delivery capacity of the government.

Thereafter, the requisite and more complex structural reforms that we have long advised on, in areas ranging from the labour market to education policy, can follow.

What will happen if this is not done?

Should the government continue down its present path and should the current extent of citizen abuse continue, the prospects for a de facto tax revolt become significant. If, in response, the government makes the wrong call in reacting to that revolt, the effect could easily be to inspire a broader turn of public opinion against the government which could quite plausibly set in motion a chain of events that sees the ANC face an electoral defeat in either 2024 or 2029.

Put differently, our read of South Africa is that its internal balance of power is not as skewed in favour of the government as many in the government like to believe. On the contrary, we think the present balance is far more delicate, with citizens having the influence to turn the tables on the government if matters within the country deteriorate further. The first firm step towards such a turning is often a deficit crisis. That is what happened around the Smuts administration when it was defeated in 1948, and what happened to the National Party in the 1990s, and it is unclear to us – given your present choices, as the government – whether your administration will escape a similar fate.

The Friends of the IRR fights on your behalf to stop citizen abuse by resisting state abuses and empowering citizens with the tools and knowledge to resist in their communities. If you want to stop corruption and abuses in your community then join the Friends of the IRR. #CitizenAbuseHarmsEverySouthAfrican and when it comes to #StoppingCitizenAbuse #StoppingCorruption#StoppingStateIncompetence#StoppingRightsAbuses; #ResistanceIsEverything.

[Image: Gerd Altmann from Pixabay]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend