A year ago, as we entered the second week of the hard lockdown that heralded a year of difficulty, anger, fear, risk and mounting insecurity, I wrote about what, for me, was a vivid revelation of our failure as a country.

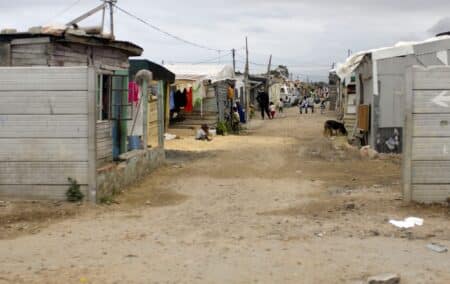

It did not come as a surprise, but it was nevertheless striking that – as I described it then – ‘(when) we South Africans went home to self-isolate on the evening of Thursday 26 March, we slipped back, the vast majority of us, into a country we thought we’d last lived in in the 1980s’.

For all the vast scale of change – for the better – since 1994, I went on, ‘most of us – in the tens of millions – have gone separately to our homes in the teeming townships and the still streets of suburbia as if there remains a law that still separates us by the inerasable logic of apartheid.’

If, as is doubtless true, the origins of this stubborn pattern can be traced back to the policies and sentiments of pre-1994 decades, the fact that the material divide remains as stark calls into question the efficacy of what were meant to be democratic-era alternatives.

Now, more than a quarter of a century later, there is no avoiding the conclusion that South Africa has doggedly pursued a path of gathering failure – and chiefly because (again, as I wrote this time last year) ‘it has tried and failed to defy the logic of economics: good schooling delivering people willing and able to succeed; economic policies that grow the economy, generating jobs and opportunities; empowerment policies that address disadvantage where it exists, and employment policies that match economic not ideological demands’.

Thus, during the lockdown – when people returned to their households – the state of the nation revealed the default segregation of communities that is commensurate with the failure to genuinely turn South Africa into a modern, free, prospering state, for all its people.

A year is not a long time, and it is surely unfair to judge progress towards socio-economic goals in a year defined by the Covid-19 crisis, but it must be possible to judge policy-makers by their intentions, especially in the face of events that call for urgency and clarity of purpose.

This is the only context in which to judge the importance of President Cyril Ramaphosa’s self-described ‘turbo-charging’ of the ruling party (along with the confidence many have expressed that he has defeated errant secretary-general Ace Magashule), as well as just how meaningful the Defend our Democracy initiative can hope to be.

Basic minimum requirement

Make no mistake, cleaner government, a vigorous endorsement of the supremacy of the Constitution, and, dare we hope, seeing the corrupt in orange overalls, would be more than welcome – but these things only really establish the basic minimum requirement of effective governance.

What it would leave in place is the entire edifice of policy-making (which is really where South Africa’s problems lie) and a more efficient implementer.

The risks lie in the key drivers of policy: the government’s unshakeable insistence on being in command of economy and society (which informs what the ANC regards as its ‘historic mission’), and the crafting of every major policy question on the basis of what South Africans look like instead of what they need and what they are capable of. The effects are reflected in deficiencies and failures across the whole spectrum of state action, from empowerment and labour regulation to service delivery (the vaccination roll-out is a telling case) and power generation.

But perhaps the most striking illustration is the drive to enable expropriation without compensation.

Consider these pointers from last week’s statement from the ruling party’s national executive committee (NEC).

With apparently commendable rationality, it asserted that ‘economic recovery is our foremost priority’, and ‘urged the business community to support the recovery process by accelerating productive investments in the economy’.

Several paragraphs later, however, the NEC lent its full support to EWC, arguing that ‘progress in Parliament on the Expropriation Bill and the amendments to Section 25 of the Constitution … confirms … that if we only rely on restitution, it will take decades to resolve the historical injustice, and hence the need to focus on land reform, redistribution and expropriation’.

The NEC statement coincided with a report commissioned by Business Leadership South Africa which included this crisp comment on property rights: ‘The more robust the protection afforded property rights, the lower the risks facing investors and therefore the higher the volumes of investment.’ The researchers added: ‘Ultimately, the less the regulatory burden placed on investors, the higher the investment quantum will be.’

So, while the NEC urges business to invest, it simultaneously deters investment.

The simple question is: why would business dream of investing in an environment defined by a draft law in which power to take property is so heavily skewed in favour of a cash-strapped, corruption-prone and incompetent state?

If, for argument’s sake, the ANC achieved what has increasingly seemed beyond its capacity and defeated corruption, overcame its debt crisis and succeeded in replacing incompetence and mismanagement across its now vast state apparatus with efficiency, the impact of its stated policy objectives would only make for a more compelling investment deterrent.

Changing things that really matter

Which is why, if people are willing to stand up and be counted in the hope of making a difference, what they should be focusing on is changing things that really matter to households across the country, to their freedom, their well-being, and their hope for a better life.

Without enterprise, and the environment that stimulates it (the dynamism of a free society and the free market that goes with it), achieving these things is doubtful.

Almost every piece of research that the Institute of Race Relations produces reveals, on the one hand, a society that is very willing to live and work together (contrary to the narrative of division that the ANC and others cleave to), and one that is united in wanting jobs and opportunities and a shot at a better life, but, on the other, a society still burdened with immense disadvantages inherited largely from the past, and a lack of jobs, opportunities and skills, and dwindling prospects largely arising from contemporary choices. The whole country is held back as a result.

It doesn’t need to be like this. But none of it will change on its own.

[Image: Andrew Shiva, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24739160]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend