It is guaranteed that tomorrow’s likely sentimental hoopla will fall far short of acknowledging that Freedom Day has become an increasingly ironic milestone of South Africa’s mounting failure to meet the ‘liberation’ project’s inaugural promise.

It is also likely that those inured to the sentimentalism will misjudge or misperceive the significance of those few historic days of change at the end of April in 1994.

Digging into my own records – things kept or written over the past 28 years – has reminded me both of the significance (and of some of the easily overlooked details) of modern South Africa’s turning point, and of the chronic falling short in the years since.

Strikingly – and it’s often glossed over – the nature of the transition was cooperative rather than convulsive, the former always having been considered unthinkable, the latter inevitable.

Yet, for all the revolutionary hostility the struggle invested in its ambition to destroy the system, from its law-making institutions to its repressive apparatus, the transition from apartheid to democracy occurred along a seamless constitutional continuum marked not by rupture but a sequence of mutually agreed dates that determined the end of the 21st South African Parliament (since Union in 1910), and the beginning of the 22nd.

And, despite misgivings among some, even the very last all-white House of Assembly sitting on 22 December 1993 signalled optimism rather than foreboding. I covered it from the press gallery in the old chamber, and this week found in my report published the next day what now seems an almost remarkable certitude in Leader of the House Adriaan Vlok’s summation: ‘I am sure that I speak for the majority when I say that we do not see this as an end, but a new beginning for a better future.’

Not that South Africa was a society universally excited about its imminent step into a democratic future.

In that same final white-on-white debate, Conservative Party leader Ferdi Hartzenberg was grimly emphatic in seeing the transition as ‘the loss of our freedom’, an event he likened to the Treaty of Vereeniging at the end of the Anglo-Boer War.

Senseless horror

And, given that the first three years of the 1990s had been far bloodier than the whole of the 1980s, it is perhaps natural that the 20 deaths in the last-gasp bombing campaign in the few days before the 27 April 1994 ballot – mounted futilely by a minority evidently determined to scupper the new system – registers less as the senseless horror that it was than as just another in a sequence of senseless horrors.

Yet the day was carried; it was unstoppable, and the vast majority of South Africans were behind it.

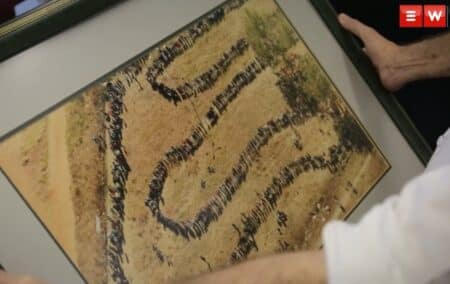

I wrote elsewhere of the first ‘freedom day’:‘Serpentine queues, some stretching for kilometres, showed that, despite the bombs of the past few days, the country’s democratic resolve was in good shape. There was plenty of patience and spirits were high. By the time they voted, many had waited for hours. Most had waited a lifetime.’

It was less challenging for some. There’s the delightful story of Oom Daantjie Snyders of Mier, a village on the edge of the Kalahari, who was not a man to take chances. Alarmed by television footage of seemingly unending queues around the country, he decided to wait until the second day of voting before making his way to the polling booth. ‘I didn’t want to vote on Wednesday,’ he explained, ‘because I wanted to avoid the rush.’ It was an undue precaution: when Snyders cast his vote, it brought the grand total for Mier to 10.

There is no question – even in places like Mier – that 27 April 1994 was a great moment in the life of the country.

But what has happened since?

Poverty and dejection are widespread, racialism is rampant, corruption pervasive, ineffectiveness and collapse evident wherever you look.

It is good to remind ourselves that democracy is intact, but, even if bombs are not a feature of our daily anxiety, we live in restive, protesting times, and for good reason.

‘To be a nuisance’

I often think of the great Anglo-Indian biologist J B S Haldane’s approving remark that ‘(the) people of Calcutta riot, upset trams, and refuse to obey police regulations in a manner which would have delighted [Thomas] Jefferson. I don’t think their activities are very efficient, but that is not the question at issue… I believe with Thomas Jefferson that one of the chief duties of a citizen is to be a nuisance to the government of his state’.

But as we prepare to mark our 27th Freedom Day, the distressingly inescapable realisation is that, in South Africa today, it is the state that has become a nuisance to the citizen.

When you perceive the open-hearted goodwill of statements such as Adriaan Vlok’s in December 1993, you have a sense of just how the optimism invested in the prospect of a better future then has been squandered and abused in the years since.

Just last week, I spotted a South African National Blood Service donor appeal, and realised how tragically ironic it was in 2021. The legend reads: ‘We need to see past what people look like and see them as the heroes they could be….’

We have the same blood, after all. We are all equivalently human.

Yet it is shocking that the basis of state intrusion into our lives today – in every sphere from property ownership, jobs and business to education and healthcare – is founded on the reverse, the very racialist notion we thought we had defeated in 1994.

Tomorrow, our political leaders will doubtless dish up dependable fare about the events of that year, and the great triumph of liberty and freedom.

Unfortunately, it will mostly be mere sentimentalism – and sentimentalism that does a profound disservice to the architects of the transition, who were first and foremost no-nonsense politicians. Nelson Mandela himself is an exceptional example.

Looking back from 2013, The Guardian’s Gary Young observed perceptively that ‘(most) criticisms of Mandela as a leader were simplistic because they started from the basis of proving or disproving his sanctity, rather than trying to understand him for who he was: a political leader guiding a developing country through a transitional phase. His singular and considerable achievement was to pave the way for a stable democracy.’

Great efforts

Relieved of all the overblown epithets stapled to his chest, we can see Mandela all the more clearly as heroic for being human, not super-human, and for achieving what he did because he made great efforts to do so.

He was flawed, he made mistakes. His overweening loyalty to his party, the African National Congress, was a blind spot.

But, as I wrote in 2014, what ‘seems true about Madiba is that while he was around, most South Africans had the sense of a shared fate which if someone like Mandela could embrace, having been through all he had been through, they could embrace, too’.

The post-Mandela danger was that ‘in the absence of any such essential affinity, we risk falling back on name-calling, othering, ethnic arithmetic and all the envy, resentment, mistrust and incomprehension that go with those kindergarten impulses’.

Too often, in 2021, that’s exactly where we find ourselves.

It’s unlikely we will hear any of this tomorrow; we will not be presented with the memory of ‘a considered leader who represents a fraternal objective, not of unanimity, but common interest’.

And the irony is that that was precisely what delivered the great shift of 1994 – a vision that the country’s leadership today actively defiles.

[Image: Still image of Associated Press photo editor and photographer Denis Farrell holding one an aerial photograph of a 1994 voting queue, from EWN’s documentary Capturing freedom: The 1994 election from a journalist’s point of view at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uwMBMfvdEsk]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend