Ace may be in, Ace may be out, but radical economic transformation will be carried on anyway.

Cyril Ramaphosa’s apparent victory over Ace Magashule has been described as a setback for the faction of the African National Congress (ANC) favouring radical economic transformation. For example, BusinessLive reported that ‘many commentators have concluded [that] the way is now cleared for President Ramaphosa to implement his reform agenda’.

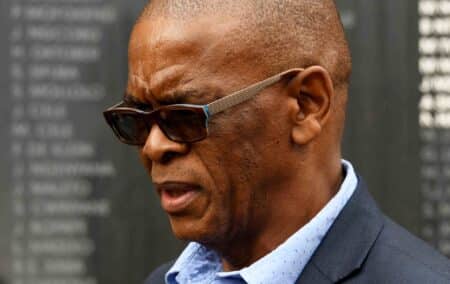

The newsletter Africa Confidential opined that the suspension of Mr Magashule, secretary-general of the ANC, was a setback for the faction of the party loyal to Jacob Zuma, which had consistently frustrated Mr Ramaphosa’s efforts to ‘end corruption, revive the economy, and renew the ruling party’. Mr Magashule’s demise could be a ‘game-changer’ for Mr Ramaphosa, an ‘incrementalist’ who had been chided by some of his own supporters for ‘being too timid and too slow’.

One of the problems of dealing with corruption is that corruption characterises the ruling elite from top to bottom. How does a party which has practised and/or condoned it and/or luxuriated in it for so long now suddenly extirpate it? The policy of cadre deployment has played a major role in fostering corruption, but there was nothing in Mr Ramaphosa’s complacent testimony to the Zondo commission to suggest that he recognised the catastrophic effects of this policy, let alone that he would even try to jettison it.

The radical economic transformation faction of the ANC may be in or it may be out, but radical economic transformation in the form of the national democratic revolution remains the party’s overriding policy. Although the communications media studiously ignore this policy – as they also studiously ignore communist influence in the ANC –the deputy president, David Mabuza, stated a few weeks ago that the ANC has to continuously renew itself in order to lead the ‘national democratic revolution’.

Capture all centres of power

Quite apart from its utility as an instrument of patronage, cadre deployment to capture all centres of power is one of the key components of the national democratic revolution. Two others are redistribution of wealth and the implementation of demographic proportionality in the form of racial quotas.

Mr Ramaphosa might well be ‘too timid and too slow’. As for his plans to ‘revive the economy’, he has yet to reveal them.

In the meantime, the national democratic revolution proceeds. Four pieces of legislation in the pipeline will all damage rather than revive the economy.

Two of them deal with expropriation of private property, and in the process undermine the protection given to property rights by the 1996 Constitution. The draft Constitution Eighteenth Amendment Bill of 2019 provides for expropriation without compensation for both land and improvements thereon to promote land reform. It also empowers Parliament to enact legislation extending the circumstances in which nil compensation may be paid.

Hand-in-hand with this bill is the Expropriation Bill of 2020. Inter alia, it empowers organs of state to take ownership and possession of any expropriated property, including but not confined to land, before the amount of compensation is paid or even agreed upon (and which may of course be nil).

Although touted as necessary to promote ‘land reform’, both these bills, which give the government open-ended power, give effect to the objectives of the national democratic revolution.

So does the Employment Equity Amendment Bill of 2020. This empowers the minister of employment and labour to set binding racial targets – quotas in all but name – for designated employers in specified parts of the private sector. This policy, which has played a key role in undermining the public sector, including government at all three levels and state-owned enterprises, is thus to be imposed on companies in the private sector.

Unfair discrimination

Also in the pipeline are a set of amendments to the Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act of 2000. That act outlawed unfair discrimination on eighteen grounds, among them race and gender. The amendments widen this list to include almost anything, discrimination being unlawful even if it is neither intentional nor unfair.

The proposed amendments go even further. As my colleague Anthea Jeffery points out, companies (and other entities) will now have a ‘general responsibility to promote equality’. This means that they must provide ‘equal access to resources, opportunities, benefits, and advantages’. They are also required to achieve ‘equality in terms of impact and outcome’.

The private sector is to be burdened with demands that are difficult to measure, and impossible to achieve. If the open-ended vagueness of the anti-discrimination requirements is Kafkaesque, the equality requirements belong in cloud-cuckooland.

So much for Cyril Ramaphosa’s reform agenda to ‘revive’ the economy.

[Image: GovernmentZA]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend