President Ramaphosa was doing the sort of thing that he does well this past weekend – making uplifting speeches, delivering good news and promising even better to come.

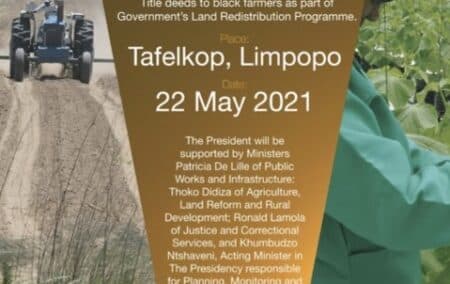

The event was the handover of title deeds to a farming community in Tafelkop in Limpopo. Against the background of historical dispossession, this was a moment for celebration. The president was certainly correct in this. Gaining ownership of something – and in this case something that signifies both belonging and livelihood – is a joyous occasion.

The farmers of Tafelkop have been there for 25 years.

‘This land is this community’s most valuable asset, and now it is officially yours,’ the president said.

‘These title deeds bring justice to a dispossessed community.’

He went on to say that this would open up new avenues for the farmers. They would be able to use the land as collateral for loans, for long-term supply contracts and to form partnerships with others.

Nodding to the glacial pace at which officialdom moves, he addressed the new landowners: ‘You have reminded us indeed that nothing is so full of victory as patience, and that where there is unity, there is always victory.’

He added that what was at issue here was not just redress or the rectification of historical wrongs, but to stimulate economic development. Agriculture, he stressed, was a growth area and offered multitudinous opportunities. Plans were afoot to expedite this.

All upbeat stuff, and hardly inappropriate to the occasion.

Not the approach of the government

Unfortunately, President Ramaphosa’s comments suggested a limited view of reality on the part of his audience, for this is not the approach of the government he leads. Quite the contrary in fact.

Ownership, and the title deeds that they symbolise, along with the justice and dignity that were so much a part of the president’s sentiments, are viewed at best ambivalently. It bears repeating that the official approach to land redistribution – that part of land reform that seeks to endow people with land as a resource (as opposed to those with a historical claim on a land parcel) – is explicitly not to confer ownership.

This is a matter of policy. The State Land Lease and Disposal Policy makes it clear that land will be granted on the basis of leases, with the option to purchase being available only after some 50 years of having worked it to the satisfaction of state officials (who might themselves have little understanding of farming). And then, only those able to produce on a significant commercial scale are to have such an option.

The face of government policy is, sadly, less that of the Tafelkop farmers than of people like David Rakgase, Ivan Cloete and Vuyani Zigana.

Rakgase became something of a symbol for the dogged statism of the land reform programme when his attempts to purchase the farm he was successfully working were resisted for the better part of a decade. The government’s position was set out with commendable clarity in its court papers: policy rested on the ‘principle that black farming households and communities may obtain 30-year leases, renewable for a further 20 years, before the state will consider transferring ownership to them’.

(The policy has reportedly been revised to shorten the period before a sale might be considered, though this has evidently been done without much publicity.)

Targeted for eviction

Ivan Cloete and Vuyani Zigana, meanwhile, were farmers who had done fairly well for themselves on state-owned farms – and then found themselves targeted for eviction and the reassigning of their farms. Indeed, similar stories hit the news prominently in 2020 when the government announced that it would ‘release’ 700 000 hectares of land for redistribution. (President Ramaphosa referred to this in his speech.)

The pattern went something like this: having built up viable farming operations, the farmers in question would find their leases cancelled or reassigned. This appears to have been connected to the machinations of bribe-demanding officials and politically connected businesspeople.

With title, the farmers of Tafelkop will have some protection from this. This is good, and would have been a subject for the president’s speech. But it should be noted that they are not typical of the beneficiaries of the government’s programmes.

For the Tafelkop farmers, however, an issue of some concern could well be the government’s plans to expand its latitude to intrude into private property, its expropriation without compensation agenda. In his inimitable style, the president put a positive spin on this: ‘We are forging ahead with the process of amending Section 25 of the Constitution to enable land expropriation without compensation, all the while ensuring that we improve agricultural output and expand the property rights of all South Africans. There is currently a public participation process around the Expropriation Bill, which outlines the circumstances under which land may be expropriated both with and without compensation.’

Unconvincing

This is, of course, unconvincing. The entire policy drive has been premised on giving the state greater leeway to deprive people and institutions of their property. When you take into account a dysfunctional and all too often venal state, the outcomes are unlikely to be salutary.

Tafelkop is indeed an inspiring story – because of the grit and determination of a community, less because of government than despite it. May it have a happy and prosperous future. Indeed, may the government see in this the pattern for the future, rather than an isolated exercise, of significance only to itself.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend