This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

9th June 747 – Abbasid Revolution: Abu Muslim Khorasani begins an open revolt against Umayyad rule, which is carried out under the sign of the Black Standard

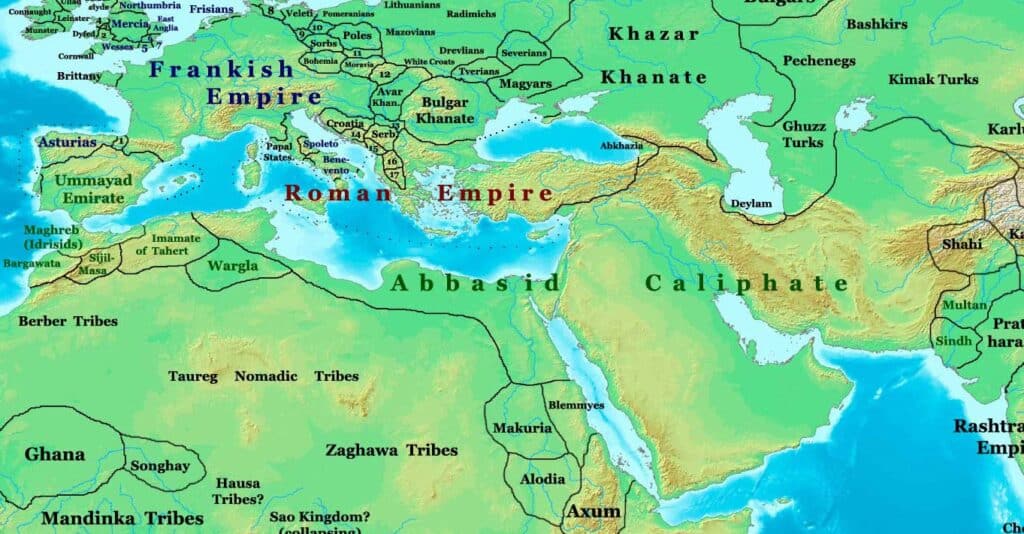

After the initial expansion of Islam and the march of Arab armies out of the Arabian Peninsula in the 600s, the territory under their sway expanded rapidly to encompass most of the Persian and Eastern Roman empires. Between 632 and 661, the so-called Rashidun Caliphs (that is the ‘rightly guided’ Caliphs) established a Muslim-Arab empire that stretched from the borders of modern-day Tunisia to the Western borders of modern-day Pakistan, and from the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula to the Caucasus Mountains.

The leaders of the Caliphate derived their authority from their claim to be the successors of the Muslim prophet Muhammed. Caliph means ‘successor’. The early mainstream Islamic world view was that, ideally, the whole Muslim community or ‘Ummah’ should be united under the leadership of one Caliph. The only problem was that there was no clear agreement on how this Caliph should be chosen. This question plagued the Islamic world from its earliest days in the aftermath of Muhammed’s death, and is the origin of the main divides in the Islamic world, notably between the two main Sunni and Shia branches.

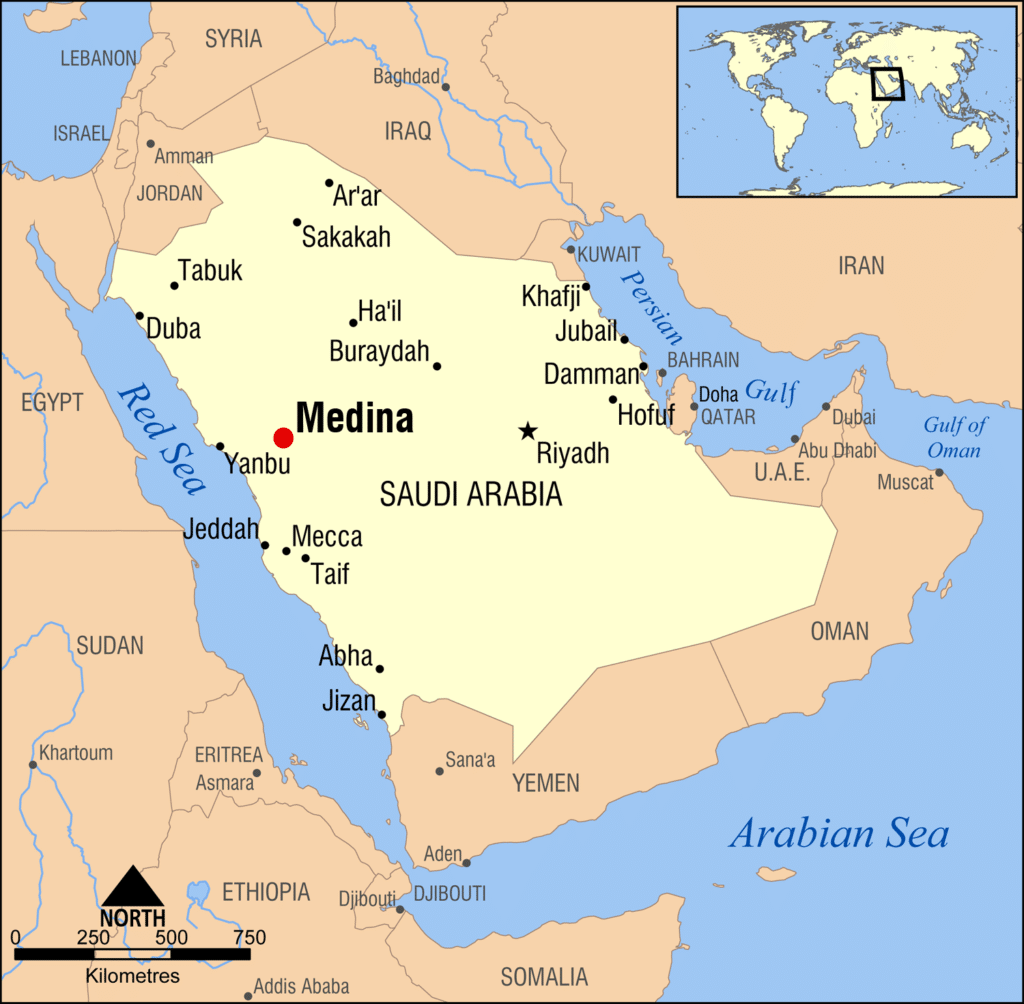

Sunnis believe Abu-Bakr to be the first legitimate Caliph, as they say Muhammed instructed them to elect a successor to lead the Ummah from among his companions. Abu-Bakr was elected by the companions and people of Medina.

Shias, by contrast, believe that Muhammed intended his cousin and son-in-law, Ali, to claim the title of Caliph on the grounds of his family connection to the prophet. (Shia is an abbreviation of ‘Party of Ali’ in Arabic).

Another group who would appear later in history called the Kharijites, believed that the Caliph could be any Muslim so long as he was the most pious and righteously guided Muslim in the community.

The radical faction among the Kharijites believed that Muslims who committed sin were the same as infidels and must be killed. The moderate faction of the Kharijites would go on to form the smallest branch of modern Islam, the Ibadi (found mostly in modern-day Oman).

While disputes among the Rashidun Caliphs began with the death of Muhammed, they were at first fairly subdued. Abu-Bakr was accepted by almost all Muslims and Arabs under the rule of the Caliphate, and only some – like Ali – refused to acknowledge his rule. During this time the Islamic armies were focused on lightning conquests of Persian and Roman land, and the rapid expansion and loot soothed tensions in the political elite. On his deathbed, Abu-Bakr appointed his friend, Omar, as the next Calpih. Omar began more firmly establishing the Caliphate’s government; he ruled with a light hand, not requiring any of the people’s conquered by the Muslims to convert to Islam, so long as they acknowledged his rule.

Seeking to try and reduce the tensions associated with the succession, Omar appointed a committee of six men to choose the next Caliph from among themselves. This committee settled on two candidates, Uthman and Ali, (who still claimed he should have been the Caliph all along). Shortly thereafter, Omar was assassinated by a disgruntled Persian soldier who was angry at being taxed too heavily.

Uthman was then selected to succeed Omar, a decision which likely greatly upset Ali, as he had now been denied leadership three times.

Uthman’s time as leader was initially successful – the last parts of the Persian empire were conquered, and Uthman protected private property to a degree in the newly acquired regions while also encouraging trade. Things would change as the loot from conquest began to dry up, and Uthman’s tendency to appoint family members to positions would build resentment against him.

Egypt in particular began to be dissatisfied with his rule, and protests and riots began to erupt across the Caliphate, with many rebels calling for the appointment of Ali as Caliph and for Uthman to resign.

In 656, a group of rebels, mostly from Egypt, marched to the Caliph’s residence in the city of Medina and put him under siege in his own house.

Eventually Uthman was able to talk them down and convince them to withdraw. However, a letter soon reached the rebels as they were on their way to Egypt, allegedly written by Uthman, ordering their execution once they returned to Egypt. While the letter was likely a forgery, the rebels believed it to be real, returned to the city and attacked Uthman’s house, killing him.

This assassination of the Caliph by Muslims shocked and polarized the Islamic world. In the aftermath, Ali was finally declared Caliph, becoming the 4th Caliph of Islam in the Sunni world view (Ali remains the first Caliph in the Shia world view). Soon there were calls for vengeance against the murderers of Uthman, and some of Uthman’s supporters, notably from the Umayyad family, began agitating against Ali. Muhammed’s third wife, Aisha, gave a fiery speech denouncing Ali because Ali had refused to execute the murderers of Uthman, who had supported his elevation to the Caliphate. A civil war soon broke out between supporters of Ali and forces loyal to Uthman, a conflict known as the First Fitna.

In late 656 forces led by Aisha were defeated by troops loyal to Ali and she surrendered and was sent back to Mecca and given a pension to buy her compliance. Ali’s fight for control did not end there, however, as the Umayyad governor of Syria, Mu’awiya, refused to declare allegiance to Ali, and the two sides soon came to blows.

Throughout June and July of 657, the forces of Mu’awiya and Ali battled for control of the Islamic world. The fighting was going the way of Ali but was ultimately inconclusive. Eventually a portion of Ali’s army convinced him to negotiate with Mu’awiya and see if a non-violent solution could be found. This outraged the hardliners in Ali’s army, who defected to form their own movement, which would go on to become the Kharijite movement. They opposed both Mu’awiya and Ali, their slogan being ‘arbitration belongs to God alone’.

Arbitration between the Umayyads and Ali soon collapsed and fighting resumed. With Ali now weakened, the Umayyads gained ground. In 658 Ali’s forces had to move against the Kharijites to secure their flank and allow them to regain momentum against the rebels.

At the Battle of Nahrawan in central Iraq, Ali’s forces smashed the armies of the Kharijites, who withdrew from the battle to continue the war through raiding, assassination and terrorist attacks (some modern scholars claim that modern-day Al-Qaeda and ISIS are neo-Kharijite, though modern Islamist radicals strongly reject this association).

Despite his victory over the Kharijites, Ali’s forces continued to lose ground to the Umayyads, and in 661 a Kharijite plot to assassinate all leaders of the civil war so as to bring it to an end managed to kill Ali but failed to kill his opponents. Ali’s son, Hassan, soon sued for peace with Mu’awiya and the Umayyads, and Mu’awiya was made the first Caliph of the Umayyad dynasty and the 5th Caliph of Islam, ending the Rashidun Caliphate.

From 661 until the late 740s, the Umayyads ruled the Islamic world, expanding their territory across North Africa and into southern Spain. The Umayyads still ruled over an empire whose people were mostly Christians and so they tended to be fairly tolerant, appointing many Christians into the lower and middle ranks of their administration, while reserving only the top positions for Muslims. During this period the Umayyads absorbed much of the former Roman administrators of Syria and Egypt and the Persian administrators of Iran into their empire and their military and governance became more like that of the Romans and Persians.

The Umayyads did, however, strongly favour Arabs over other Muslims, and the Umayyad Caliphate has been seen as a time of Arab dominance over the Islamic world, with Muslim elites among the Berbers, Egyptians, and Persians becoming increasingly frustrated with the Umayyads.

The Umayyads also managed to permanently split the Shia Muslims away from Sunni Islam in 680 after the death of the first Umayyad Caliph, Mu’awiya. Ali’s son and grandson claimed that as part of the peace treaty, Mu’awiya had promised not to establish a dynasty and so rule of the Caliphate would likely pass to Ali’s son.

Mu’awiya’s successor was Yazid, who demanded the submission of Ali’s grandson Husayn. Husayn saw himself as a more legitimate heir and refused to submit, travelling instead to Iraq to meet with his supporters. He was intercepted by Umayyad troops and, when negotiations failed, Husayn (a grandson of the prophet Muhammed) and his close family were massacred. (The site of the massacre is a holy place for Shia Muslims.)

This massacre set off another civil war in the Islamic world, called the Second Fitna. It would be won by the Umayyads, but would permanently split Shia Islam into a separate branch of Islam with its own practices and doctrines.

The discrimination against non-Arab Muslims and the lingering bad blood caused by the killing of Husayn would cause discontent to rise against the Umayyads. In 744 a civil war broke out again between competing claimants to the Caliphate among the Umayyads, which greatly weakened their authority and sowed the seeds of another revolution.

On 9 June 747, a Persian Muslim general called Abu Muslim began an uprising against the Umayyad dynasty. Support for the revolt soon swelled across the Caliphate, as Persians, Shias, Kharijites and Arab tribes who were rivals of the Umayyads joined the revolt.

The Abbasid armies quickly pushed back the forces of the Umayyads, and in January of 750 defeated them at the Battle of Zab, crippling the Umayyad armies and causing the Umayyad family to flee to Spain, where they would eventually establish the Emirate of Cordoba.

The Abbasid Caliphate would last in some form or another until 1517, when it was abolished by the Ottoman Sultans.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend