This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

20th June 1756 – A British garrison is imprisoned in the Black Hole of Calcutta

During the 1700s, there were major shifts in India’s balance of power. The once mighty Mughal Empire, which had dominated the sub-continent, was in terminal decline (Something you can read about in this edition of This Week in History.)

Revolts by the Mughal provincial governors and the growing power of the Mahatha Confederacy had reduced the once great empire into a husk waiting to be replaced.

Into this power vacuum the French and British sought to carve a space for themselves, and more importantly, block the expansion of the other. The French and British East India companies sought to grow their influence in India by establishing more trade posts, signing deals with local rulers and, perhaps most significantly, by building forts.

In 1756, war between France and Britain was growing ever more likely (and indeed in that year the Seven Years’ War between them would break out), so British outposts around the world began to look to their defences in order to protect themselves from French attack.

Once such British outpost was the trading post at Calcutta. The area around the trading post was controlled by the Nawab of Bengal, Siraj-ud-Daulah, nominally a governor of the Mughal Empire, but in reality, an independent lord of a powerful kingdom covering modern-day Eastern India and Bangladesh.

While the Nawab enjoyed the trade that the British brought to the region, he was concerned that should the British fortify their trading post with modern masonry and guns it might make them very difficult to deal with should relations turn sour.

So the Nawab passed edicts which prevented the British and French in the region from fortifying their trade posts without his permission. As war between France and Britain loomed, both sought to fortify their positions in Bengal. The Nawab quickly issued orders reminding the Europeans of his ban on fortifications; the French stopped their building, but the British continued, prompting a furious response from the Nawab.

A Bengali army marched on the British trading post, which had an old fort protecting it, and laid siege to it. Without the modern upgrades and with many of the British Indian troops defecting to the Nawab’s army, defence of the fort proved hopeless, and the British commander ordered all troops to escape the fort.

Only 146 British soldiers, some Indian soldiers in British employ and British civilians were left in the fort under the command of John Zephaniah Holwell, an East India Company bureaucrat. The fort fell to the Bengali forces on 20 June 1756.

Holwell met with the Nawab after the fall of the fort and, according to his account, was promised that no harm would come to him or the prisoners. The Bengalis looked for somewhere to keep 60+ prisoners in the fort and that evening decided to place them in the captured fort’s small prison.

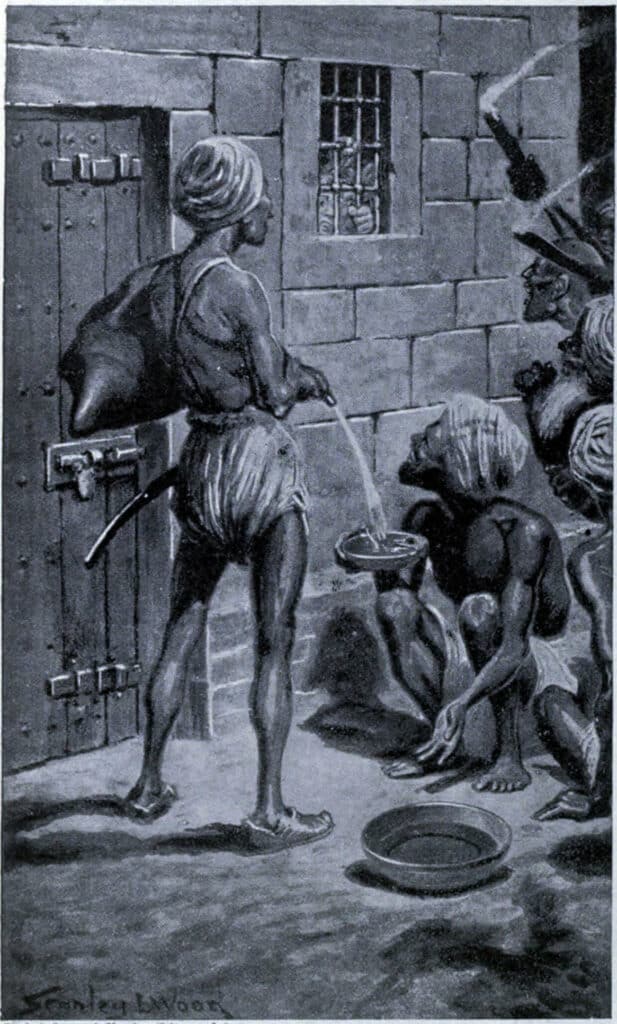

The prison (known in soldier’s slang as the ‘black hole’) was a room with two windows, with iron bars over both windows, and a strongly barred door. The room measured 4.3 x 5.5 meters and was designed for holding just two or three prisoners. Into this room were crammed all of the prisoners, who numbered at least 60 but may have been more than 146. So many were forced inside that the jailers struggled to shut the door.

Panic soon set in among the prisoners, some of whom began to suffocate. Bribes were offered to the guards to move them, but the guards were unwilling to do so without the permission of the Nawab, who was asleep at the time and whom they feared to wake. During the night of 20 June, the majority of the prisoners were crushed to death or suffocated. Only 23 survived, including Holwell, who wrote the most famous account of the event.

The next morning the door of the prison was opened and the survivors were taken out to other prisons.

When news of the atrocity reached Britain it sparked outrage, and a force was soon sent to punish the Bengali Nawab. A year later, in 1757, at the Battle of Plassey, Colonel Robert Clive, leading a force of British and allied Indian troops, defeated the army of the Nawab of Bengal, and placed a puppet ruler in his place.

This battle would mark the beginning of British expansion over India and the end of its independent kingdoms.

24th June 1535 – The Anabaptist state of Münster is conquered and disbanded

The 1520s was a time of incredible turmoil and strife in central Europe. A few years earlier, the monk Martin Luther, had published his 95 Theses, which was critical of church practices. Within a few years the church had split, with many new theological Christian movements springing up, especially in Martin Luther’s Germany. The Reformation had begun and, with it, the Protestant movement. Into this mix German peasants – who were increasingly frustrated in many parts of Germany by the rule of the nobility, and spurred on by radical preachers – began a revolt against the nobility in 1524.

This revolt was crushed, but many of its ideas remained alive across the country. In 1534, a radical group of Protestant Christians, called Anabaptists, seized control of the city of Münster in western Germany. The Münster rebels were extremely radical for the time, not only in their religious views but also in their belief in polygamy and the equal sharing of all wealth across the community of the faithful, a view which has been described as proto-communist.

The capture of Münster and the attempts to spread its ‘revolution’ to the surrounding towns prompted a response from the local nobility and the Catholic Church.

Within two months, the former bishop of the city, Franz von Waldeck, had returned with an army and laid a siege.

The leader of the rebellion, Jan Matthys, believed they would be protected by God and so sallied out of the city to fight the besieging army with only 12 followers.

He was quickly killed, his head placed on a pike and his genitals nailed to the city gate.

His successor within the city, John of Leiden, soon claimed to have received additional instructions through divine vision and swore to hold out against the attackers.

John declared the city to be ‘The new Zion’ and, due to the large number of women in the city, made polygamy compulsory. He reportedly took 16 wives.

A period of violence followed within the city as the increasingly radical Anabaptists sought out opponents and executed them.

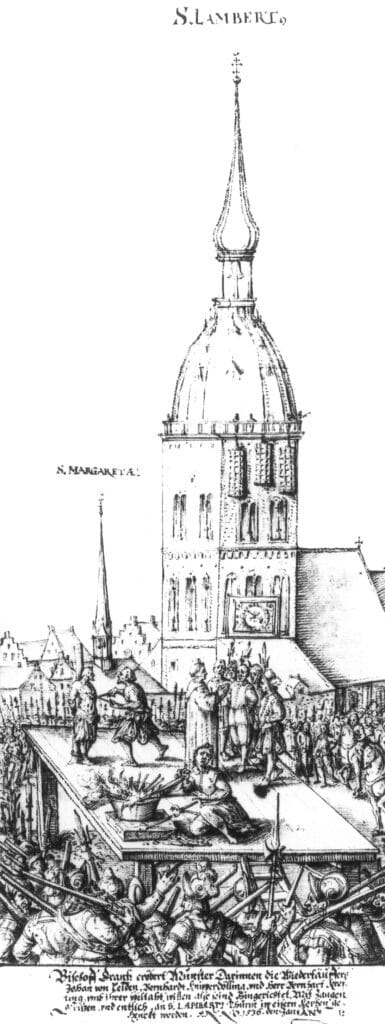

Eventually, after a year of siege, the now-starving city was forced to surrender on 24 June 1535.

The rebel leaders were rounded up and executed.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend