The real problem about ‘critical race theory’ is that it’s really Uncritical Racist Theory – that is, if you can classify such irrationalist hypocrisy as ‘theory’.

First of all, it is racist because it asserts race as the foundation of human society and of theory. It is no different, theoretically, from Nazism, which also claimed race to be the foundation of society and history. Hitler graded Jews as sub-human, devilish antagonists of the Germans, who were the pinnacle for him of the Aryan ‘race’. ‘Critical race theory’ simply does Nazism upside down. Whites up – whites down.

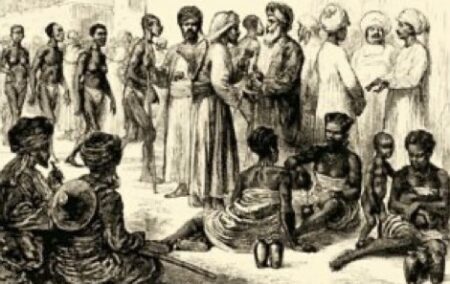

Next, ‘critical race theory’ is a liar about the history of Africa, and of black people. It suppresses all reference to the thirteen hundred years of Islamic enslavement of black Africans as ‘kuffar’ (infidels, and therefore legitimate for enslavement), which began not long after the death of the prophet Muhammad, who himself enslaved Jewish women and children he had captured in jihad in what later became known as Medina.

Enslavement of black Africans in southern Africa from tribes that were classified as ‘kuffar’ by black African slave-hunters based at Angoche in northern Mozambique only ended when the Angoche slavemasters were militarily defeated by the Portuguese colonialists in 1910.

As I noted in my article, ‘A lethal censorship of black history’ on Politicsweb on 8 October 2020, ‘Stokely Carmichael made his home in Guinea for the last three decades of his life, without reference to the hundreds of years of Islamic slavery in Guinea as part of the Mali Empire before European colonisation.

‘As the North African Arab scholar, Ibn Khaldun, noted, the grand pilgrimage to Mecca of Malian emperor Mansa Musa in 1324 (724 in Islamic history) consisted of 12 000 slaves.

‘Slave women and men’

‘“At each halt, he would regale us [his entourage] with rare foods and confectionery. His equipment furnishings were carried by 12 000 private slave women (Wasaif) wearing gown and brocade (dibaj) and Yemeni silk […]. Mansa Musa came from his country with 80 loads of gold dust (tibr), each load weighing three qintars. In their own country they use only slave women and men for transport,but for long journeys such as pilgrimages they have mounts.”’

Among Middle Eastern slave-trading states and recipients of African slaves, ‘slavery was legally abolished in Saudi Arabia and Yemen only in 1962, following its abolition in Iran in 1929. In Oman slavery was made illegal only as late as 1970.’

The Wikipedia entry, Slavery in Mauritania, states that slavery ‘has been called “deeply rooted” in the structure of the northwestern African country of Mauritania, and “closely tied” to the ethnic composition of the country.

‘In 1905, an end of slavery in Mauritania was declared by the colonial French administration, but the size of Mauritania prevented enforcement. In 1981, Mauritania became the last country in the world to abolish slavery, when a presidential decree abolished the practice.

’However, no criminal laws were passed to enforce the ban. In 2007, “under international pressure”, the government passed a law allowing slaveholders to be prosecuted.

‘Despite this, in 2018 Global Slavery Index estimated the number living in slavery in the country to be 90,000 (or 2.1% of the population), which is a reduction from the 140,000 in slavery figure which the same organisation reported in 2013, while in 2017 the BBC reported a figure of 600,000 living in bondage.

‘Sociologist Kevin Bales and Global Slavery Index estimate that Mauritania has the highest proportion of people in slavery of any country in the world. While other countries in the region have people in “slavelike conditions”, the situation in Mauritania is “unusually severe”, according to African history professor Bruce Hall, and comprises largely of a black population enslaved by Arab masters.

‘The position of the government of Mauritania is that slavery is “totally finished … all people are free”, and that talk of it “suggests manipulation by the West, an act of enmity toward Islam, or influence from the worldwide Jewish conspiracy”. According to some human rights groups, the country might have jailed more anti-slavery activists than slave owners.’

Reminiscent of Adolf Hitler

That anti-Semitic, anti-Western response, reminiscent of Adolf Hitler, has its echo in CRT.

Given that southern and western Mauritania were part of the Mali empire of Mansa Musa, it is clear that slavery there in the 21st century continues a history that began centuries before white Western colonialism.

Captured in Guinea, black slave men and women formed a base in the same way of the despotic and murderous regime in Morocco of Sultan Moulay Ismail many centuries before Morocco was occupied by France, with hundreds of thousands of white Christian men and women enslaved there as well.

In his study, ‘Expediency, ambivalence and inaction: the French Protectorate and domestic slavery in Morocco, 1912-1956’, published in 2013, R. David Goodman noted that ‘a clandestine slave trade continued along with domestic slavery throughout the French Protectorate, from the 1912 Treaty of Fes to independence in 1956. Notably, on the eve of decolonisation, a French colonial official recorded payments for royal slaves without any remark.’

CRT is a racist lie which helps to perpetuate the slavery of black Africans in Mauritania at this very moment.

To the advocates of CRT, I would say: answer that. But they won’t, because they can’t.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend