The job of a historian is to discern links between seemingly unrelated events.

Some would argue that the decision by the Americans to support Islamist fighters in Afghanistan against their great ideological enemy, the Soviet Union in the 1980s led to the Arab Spring some thirty years later. Or that the price of bread in late-18th century Paris led to events which shaped modern Europe (and, given Europe’s outsized role in the globe subsequently, the world as we know it today).

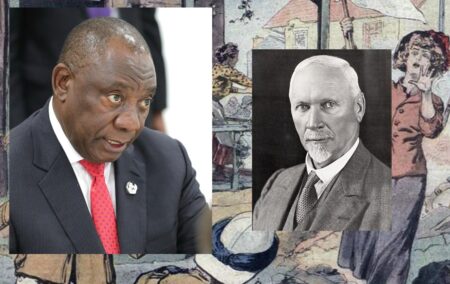

And perhaps the Rand Revolt in 1922 in what is today Gauteng sparked off a series of events that led to the National Party victory nearly a generation later, and to the introduction of apartheid.

Now, before you slam your laptop shut or throw your smartphone against the wall in disgust at such a ridiculous leap in logic, let me explain the reasoning.

The 1922 Rand Revolt was sparked by economic grievances among white workers whose wages stagnated following a drop in the gold price as a result of the global economic slump after the First World War. This prompted the mining houses to weaken the colour bar and allow black workers to do more skilled jobs (at a lower wage than their white counterparts). A telling slogan of the time was ‘Workers of the world unite, for a White South Africa’.

This uprising, which lasted four months, was crushed by Prime Minister Jan Smuts, using troops as well as the then fairly new technology of war planes. My hometown, Benoni, still has the singular distinction of being the only South African town to have been bombed from the air (some wags may suggest the fair city could be improved by another round of ordnance being dropped on it).

Smuts’s actions provoked a backlash, with an alliance between Barry Hertzog’s National Party and Colonel Frederic Creswell’s Labour Party unseating the Prime Minister in the 1924 election. The National Party was to be the primary force in the South African government for a decade, until Smuts and Hertzog formed the United Party in 1934, in reaction to another economic crisis.

Might have been very different

Without a Rand Revolt, Smuts would likely have held on to power in 1924 and the rise of Afrikaner nationalism, which led to the victory of a reformed National Party in 1948, might well have been tempered, and the second half of South Africa’s 20th century might have been very different.

But could the unrest we are seeing sweeping across KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng be Cyril Ramaphosa’s Rand Revolt moment?

Of course, it is far too early to say what the long-term results of this unrest will be, but it’s worth speculating on. It is very unlikely to lead to the fall of Ramaphosa and the African National Congress (ANC) government, but it has laid bare the fault lines of South Africa.

The tepid response to the crisis by the president and his government will likely shatter the illusions of many people who clung on to the hope of a New Dawn. At the same time, the ANC’s decline in KwaZulu-Natal, which began in 2019, will continue. In the general election that year the party scored 54% of the vote in KwaZulu-Natal, a drop of ten percentage points compared to 2014, and this is now likely to continue.

The question, however, is who will stand to benefit from an exodus of voters from the ANC. The ANC’s long-term rival in KwaZulu-Natal, the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), could see another gain, after jumping to 18% in 2019 compared to the ten percent it won in 2014, if the Zulus who abandoned it for a Jacob Zuma-led ANC return.

The Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) could also stand to benefit, and they have been making significant inroads in KwaZulu-Natal in recent times, particularly in the province’s urban areas.

The joker in the pack may be the African Transformation Movement (ATM), an organisation formed with what was almost certainly Jacob Zuma’s tacit approval. KwaZulu-Natal was one of the only two provinces (the other was the Eastern Cape) in which it won a seat in the provincial legislature. Also telling is the fact that Mzwanele Manyi, a leading figure in the ATM, is now a spokesman for the former president and his family.

Likely to accelerate

In the rest of the country the slide in ANC support, which began in 2009, is likely to accelerate. Although it will continue to hold support in its rural heartlands, particularly in Limpopo and the Eastern Cape and to a lesser extent, Mpumalanga (as has been evident in its performance in various by-elections over the past few years), in cities and other parts of the country, its haemorrhaging of support will continue apace.

Again, the question is who will be the beneficiaries? The EFF will likely be one (although its leadership seems to be as clueless as the ANC’s, tweeting race-baiting nonsense and offering very few solutions).

Perhaps the Democratic Alliance could well surprise, with its leader, John Steenhuisen, being one of the few national political figures to be ‘on the ground’ in KwaZulu-Natal. And there is also Herman Mashaba’s ActionSA, which seems also to have taken a firm stance against the current situation.

Of course, this is speculation and perhaps the current crisis will simply blow over and be forgotten in a month. However, this is unlikely. The unrest in the country is a historical before-and-after moment. South Africa was not the same after the Rand Revolt, and South Africa will not be the same after this current episode.

President Ramaphosa and the state which he leads have shown that they are not up to the task of handling the crisis, with citizens (of all races) having to make a stand to protect property and their communities.

Episodes of violence

Of course, post-apartheid South Africa has seen episodes of violence before, but it’s probably fair to say that it has not been as widespread as this in the country’s democratic history.

Future historians may well identify this moment as the point at which the ANC finally entered its death spiral. Let us hope that it will not also be identified as the moment that heralded the beginning of the end for South Africa.

[Image: Background – Le Petit Journal 26 March 1922 http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k717516r.image, PD-US, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31850297]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend