AT the outset, readers need to know that I am deeply suspicious of large financial institutions – though perhaps not so deeply antagonistic as Rolling Stone journalist Matt Taibbi (who, in 2009, famously described US financial giant Goldman Sachs as a ‘great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money’). But still ….

I was first introduced to the workings of the large insurance companies in South Africa in the mid-80s, having landed the job of Finance Editor of The Star when it was still part of dominant media group, Argus, and had high levels of integrity.

In those days, The Star was the largest daily newspaper in the country, with a circulation in excess of 250 000. That figure began to fall after the group was sold, first to Irish media baron Tony O’Reilly, to become the Independent Media Group, and subsequently to Iqbal Survé.

Being a senior editor of a major newspaper such as The Star, whose copy was also carried in The Argus and Pretoria News, you became a prime target for the PR departments of the Big Three assurance companies, Old Mutual, Sanlam and Liberty Life.

That was before the new breed of asset managers, such as Allan Gray, Coronation and Investec (now Ninety One), came on the scene.

I was wined and dined up and down the country, with trips to game lodges and expensive destinations, with unlimited expense accounts on offer all the time. It was all done with one objective in mind: to get you on ‘their’ side and write wonderfully complimentary reports on their company and products.

The insurance companies were gathering massive numbers of assets into their life insurance-based product, such as endowments, retirement annuities, 10-year back-to-back endowments and so forth. They were not keen on unit trusts, as those were far more transparent and open about their fee-structures than the ubiquitous products mentioned above.

In fact, the level of transparency was almost non-existent in the assurance companies’ very expensive and poorly performing products. Once you were sold such a product, you would find all the odds were stacked against you.

Very poor outcomes

Much of this was due to the front-end loading of fees which, combined with investment contracts over 20 to 30 years and longer in some cases (they are still affecting investors today), delivered very poor outcomes, by and large. Very few investors – myself included – could show any real return on their money in certain of these inherently defective products.

Remember, this was in the days before the internet and the various social media outlets, where you can vent your spleen to your heart’s content today.

But there must have been some kind of almost puritanical streak in me, back then, which led to my asking more questions than I perhaps should have. At the time, I also started The Star Investment Club, which I ran from 1986 to about 1994, when I left to start my own investment advisory business.

This club soon had thousands of members, who were invited to write to me with their personal financial questions, which they did, in their hundreds….

I was almost a one-man Hello Peter, trying to investigate and answer as many of the letters I received as I could.

And very soon it became apparent to me that the single largest complaint was about the life insurance products that were sold to people. There existed a very large chasm between what was ‘promised’ during the sales process and the outcome.

I started delving into this issue and the more I learnt the more horrified I was, especially when I experienced the same with my own investments. Seven years into an endowment contract, I thought – based on my back-of-envelope calculations – that I was good to withdraw a couple of thousand rands. But I was mistaken. In fact, when I tried to cash in my policy, I was told that it had a negative value, due to the 28-year term of the contract.

Never stated anywhere in writing (apart from in the Master Policy, somewhere in the head office), these upfront costs were calculated on day one and served as a loan account against your own policy, which had to be repaid over time. Thousands of investors were sold these defective products.

Warning the public

I started asking—and writing—about these products and started warning the public to question the claims made by the large life insurance companies much more thoroughly.

Suddenly, the invitations to events and weekend-getaways in Cape Town/Sun City/Wild Coast and other exotic destinations dried up.

After one particular article—in which I questioned some of the structures of some Liberty Life endowments—I was hauled to the editor’s office to face off with the very intimidating Professor Michael Katz, legal counsel for Liberty, who was at his ‘hair-dryer’ best during our confrontation.

I was told, no doubt under heavy pressure from people concerned about the potential loss of advertising revenue, to back down from raising my concerns on these products.

Most of those products have since been discontinued, mostly the ones where you can sign up an unsuspecting member of the public into a 28-year contract (with all the subsequent front-end loading of costs) without the investors even being made aware of it.

I also came across a contract where a 10-year investment term was turned into a 28-year term by a simple falsification on the investment application.

Fast forward to today, and the influence of these large investment companies still remains, perhaps not as obviously and blatantly as in the past, but it still there.

It is well known that the investment returns on the JSE over the past three, five, seven and ten years have not been great. In fact they have been quite disastrous for millions of investors, many not so well-informed, who have experienced very little growth on their investments with some of these insurance companies who were quite willing and very able to take money from investors and not give much back.

JSE versus world markets

For several years I have been shining a torch on the ever-worsening relative performance of the JSE versus world markets, particularly in US dollars, starting around 2011. The downturn in the global commodity cycle had much to do with it. However home-grown factors such as state capture and endemic corruption, combined with the ever-socialist political objectives of the ruling ANC, turned this under-performance into a bloodbath for most South African investors.

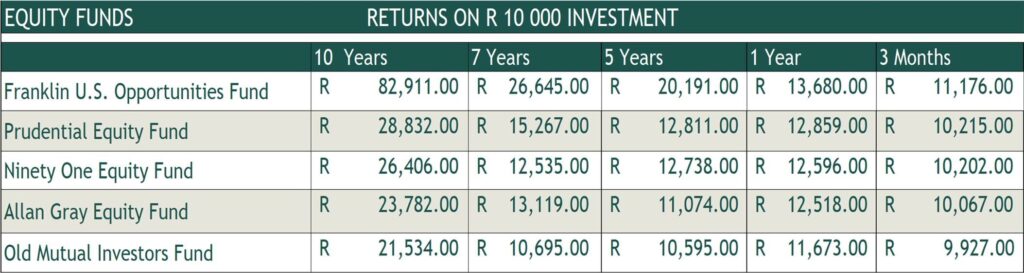

See for yourself how a R10 000 investment into the four largest local equity funds compares with that of a fairly good US-based equity fund, one I have been recommending for 10 years and more.

After being one of the top markets in the world for more than a century, the JSE has, over the 10-year period to end 2020, turned into one of the worst global markets when measured in USD terms, which it should be.

I was fortunate enough to have public exposure via my columns on Moneyweb and the Afrikaans radio programme RSG Geldsake.

Week after week I raised the issue of the JSE’s underperformance versus world markets, only to be told via feedback from the local asset managers that one must not judge performance over the short term, as it was bound to recover. But as the one year under-performance turned into three years, then five, seven and now ten years, that line of argument has fallen by the wayside.

On purely statistical terms, the underperformance over the last ten years cannot be ignored anymore. Now the counter-argument is being based on (a) patriotism; b) loyalty to country; and (c) if you don’t like it here, you must f#ck off.

But the REAL reason that South Africa’s large investment giants have defended their argument that ‘local is lekker’, is that ‘local investments are far more profitable to them’. Concern about investment returns to local investors is mostly accidental.

Substantially larger

The financial margins on local funds are substantially larger than even in-house offshore funds. And when compared with the total expenses of global investment giants, local funds are 2-3 times more expensive.

So the outrage in this ‘local versus offshore’ debate has more to do with protecting the massive salaries and bonuses of senior management/fund managers, nothing else.

Therefore it was hardly surprising that, earlier this year, due to a sudden upturn in the commodity cycle (which no-one could have predicted), as well as the base-effects of the rand dropping to R19,35/USD in April last year, the one-year figures of the JSE looked particularly good.

Suddenly there was a flurry of articles, editorials and road shows in the broader investment community about how the JSE was suddenly THE top investment destination in the world. Yet, this was mostly window-dressing, as the relentless outflow of foreigners from the JSE continued unabated.

Stuart Theobald, chairman of research house Intellidex, wrote a particularly nasty piece about advisers who ‘urged their clients to sell all local assets and bought US dollars when the rand was R19,35’. It was a typical straw-man argument, not factually correct and full of hot air and emotion. It was a surprise coming from Theobald, whose columns are normally balanced and worth reading.

Firstly, anyone who knows something about offshore investing knows that the process of liquidising local assets, getting offshore clearance and then actually moving the money takes weeks, if not months.

Secondly, the article suggested that investors took their money and placed it into a USD money market account, and there ‘lost 30%’ on the back of the rand’s increase against the greenback. Again, this is silly and uninformed, as no investment advisor would have repatriated growth assets from South Africa in order to invest in zero interest-bearing US deposits.

In fact, in spite of the rand rising by more than 30% against the US dollar, any global sectors (technology, health care, artificial Intelligence and biotech) have still outperformed the local market.

Eight-year period

To illustrate just how poorly the local market has done, I calculated the rand value of a R10 000 investment into three Old Mutual funds over an eight-year period to July 2nd 2021.

And, just to keep it in-house and not be accused of cherry-picking, I selected three funds from the Old Mutual stable.

The Old Mutual Investors fund (OM’s largest local equity fund with R12bn in assets) grew from R10 000 to R16 000, the OM Property Equity fund was virtually unchanged at R10 084 (yes, dear readers: that’s no typo), while the OM Global Equity fund was worth R33 268 on the same day.

But guess which fund was tipped as a ‘long-term keeper’ by Stephen Cranston in the latest edition of the Financial Mail: the Old Mutual Investors fund. Over a five-year period the fund actually gave you a return of 1,45% per annum, less than the annual management fees of 1,87%.

For the life of me I couldn’t fathom why Cranston, a seasoned journalist, would select the Investors fund as a ‘keeper’. That is, until I turned the page and saw the full-page ad from Old Mutual. And then the penny dropped.

But this apparent buying of favourable comment by the asset industry is far more prevalent than most would care to know.

Most media outlets are suffering financially. Many articles on investment matters are actually thinly disguised paid-for adverts with only one objective in mind: keep assets in South Africa.

[Image: piqsels.com-id-jdsur]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend