‘(There) is … in the world at large an increasing inclination to stretch unduly the powers of society over the individual, both by the force of opinion and even by that of legislation: and as the tendency of all the changes taking place in the world is to strengthen society, and diminish the power of the individual, this encroachment is not one of the evils which tend spontaneously to disappear, but, on the contrary, to grow more and more formidable.’ – John Stuart Mill, from On Liberty (1859)

Why are liberals so willing to encourage hate speech that only risks tearing society apart, and causing hurt and anguish to those who are all too often targets of bigotry?

That’s not true, of course – the entire liberal argument holds before society the vision of individuals enjoying indivisible rights that confer dignity and respect, and protection from abuse.

But the argument that liberals are quite happy to see bigots thrive, supposedly at the cost of good people, is one that our detractors often level at us (and it’s one of the many instances in which we are invariably classified as ‘right wing’).

The most recent instance came in the wake of the Constitutional Court’s unanimous judgment – authored by Justice Steven Majiedt – overturning the judgment of the Supreme Court of Appeal in the matter involving the deeply controversial Sunday Sun column 13 years ago by journalist Jon Qwelane, titled ‘Call me names, but gay is NOT okay’. Qwelane, who has since died, used this column to describe homosexuality as ‘wrong’, ‘against the natural order of things’, and akin to bestiality, and to call for outlawing the right to same-sex marriage.

The understandable outrage the column provoked prompted the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) to take Qwelane to the Equality Court for hate speech under the Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act of 2000. When the case was finally heard in 2017, the Equality Court declared that Qwelane had committed hate speech, and ordered him to apologise in a national newspaper. Qwelane appealed, and, in late 2019, the Supreme Court of Appeal agreed with Qwelane that the Equality Act was unconstitutional for being too restrictive of free speech – arguing, among other things, that hate speech should include an element of ‘incitement to cause harm’.

Hate speech

The finding on unconstitutionality meant that the matter had then to proceed to the Constitutional Court, which made its decision against Qwelane last month. (Notably, the court upheld the Equality Act’s prohibition on hate speech in all but one aspect – it struck out the word ‘hurtful’, finding it vague and redundant.)

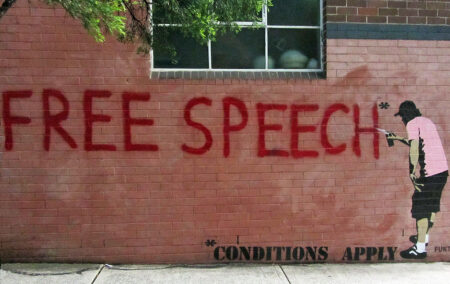

If, after 13 years, the Qwelane matter is finally settled, the free-speech argument itself is not – which is a good thing.

In his column on News24 on 4 August – Constitutional Court finally declares that hate is NOT okay – advocate Ben Winks, who acted for the Nelson Mandela Foundation as amicus curiae in the Qwelane case, turns disapproving attention on those of us who steel ourselves to make the strongest possible case for free speech.

‘This judgment strikes a blow,’ Winks writes, ‘against many politically conservative groups and individuals in South Africa who have argued for years that expression can only constitute hate speech if it is subjectively intended to incite attacks of some kind. They tend to argue that setting the bar any lower would constitute “thought control” and would only drive hateful views “underground”, rather than allowing them to be challenged in the “marketplace of ideas”.’

Winks goes on: ‘But these critics completely miss the point. The purpose of the prohibition on hate speech is not to rehabilitate the bigot or exorcise hate from his mind. The main point is not to punish, but to protect – to protect marginalised and brutalised communities from being subjected to outward expressions of bigotry, be it white supremacist symbols, apartheid denialism, rape myths, anti-immigrant tweets, or anti-LGBTIQ sermons.’

In fact, Winks is the one who misses the point. The certainty of his phrase, ‘the prohibition on hate speech’, betrays his flawed conviction that ‘prohibition’ is a guaranteed effect – the erasure of bigotry that, as he argues, thus confers protection on ‘marginalised and brutalised communities’.

‘Rot them from the inside’

He argues hopefully that ‘the judgment sends a strong message to all bigots that hate is not okay. They must keep it to themselves, and let it rot them from the inside, while the rest of us continue (in the words of the preamble to the Equality Act) “the transition to a democratic society, united in its diversity, marked by human relations that are caring and compassionate”’.

But are we really freed to continue on this exalted path?

The bigoted hold hateful and demeaning ideas not because they are permitted to, but because that’s how they think. Rendering their thoughts impermissible merely alters the conditions under which they continue to believe what they do, and – more importantly – behave as they do. They may well be that much more cautious about saying what they think – and, true enough, we can all be spared the unseemly advertisement of their insecurity and lack of intellectual maturity – but that does not reduce the risk such thinking poses, or of the conduct that wells from it.

There is, in fact, a case to be made that, rather than reducing the risk, a declared prohibition only increases it, and the protection Winks puts his trust in will likely not materialise.

Why might liberals stand up for the free speech rights of a bigot like Qwelane?

The short answer is that it’s a necessary discomfort if we are to preserve anything like an open society, and open societies are safer because they compel citizens to account for their opinions and are more likely than closed societies to enable reason to alter people’s thinking. Our own history is a stellar illustration.

‘False dilemma’

Writing on the Open Democracy website earlier this year, scholar Albena Azmanova argues unhesitatingly against what she calls the ‘false dilemma’ between ‘safe speech and free speech’.

In this piece, we gain a glimpse of the genesis of her thinking in a brief biographical reference associated with what she describes as ‘the biggest harm of all’, (that) ‘the policing of unwelcome speech eventually generates self-censorship, which nurtures intellectual cowardice’.

She goes on: ‘This is the foundation of a totalitarian outlook and the ultimate blow to freedom. I grew up in such a society and, as a university student, fought against this oppression by joining the dissident movement against the dictatorship in my native Bulgaria.’

‘Remember,’ Azmanova adds, ‘the enemies of freedom of speech are twin sisters: the bigot who attacks vulnerable minorities and, paradoxically, the militant who tries to protect these minorities.’

Azmanova’s argument (which addresses free speech on campuses specifically, though has general relevance) is interesting in part for its acknowledgement of the concerns Winks (like others) has raised in the South African context.

Noting that ‘some students feel that absolute freedom of speech on campus promotes a hostile environment that harms minority students’, she acknowledges that ‘they have argued, compellingly, that denying hateful or historically “privileged” voices a platform is necessary, so that the marginalised and vulnerable can finally speak up. They demand censorship and prohibitions against giving offence.’

As a consequence, ‘safe spaces’, ‘cancel culture’ and ‘de-platforming’, and the codifying of ‘protected categories’ of students ‘are all now part of university life’, with an ‘equal respect agenda’ being ‘enforced through disciplinary and grievance procedures, and “safe space marshals” (patrolling) events looking for macro- and microaggressions’.

But she cautions: ‘Exactly because the original vocation of free speech is to fight dogma, we should not transform it into a dogma.’

‘Long-term costs’

While arguing that ‘the grievances of those calling for a ban on offensive speech because it deepens existing injustices are valid (‘because our societies have been subjected to massive precarisation, which has indeed left many feeling homeless’) …the impulse to ‘censor offensive speech … though effective in the short-term, (incurs) long-term costs’.

‘When we exclude some views from public debate for being dangerous and unsavoury, then we miss the opportunity to rigorously contest these views. They will, however, thrive in private, safe spaces, and will continue to poison society.’

Azmanova warns: ‘Efforts to replace free speech with safe speech open the door to autocratic rule. There is no limit to what any individual might define as disrespect. Who is to decide what exactly is to be protected? And so, we pass this judgment to administrators and hand them the keys to discretionary power.’

In making the case to ‘give bigotry a tribune in order to expose it via rigorous questioning’, she acknowledges that ‘(this) is a more difficult road to take than imposing prohibitions. But this is the only road that leads away from the covert harassments of self-censure and the overt cruelties of political oppression’.

Sustaining an open society can be daunting – certainly, there’s scant pleasure in defending the free-speech rights of Steve Hofmeyr or Julius Malema.

But Thomas Jefferson had it right in professing that ‘I would rather be exposed to the inconveniences attending too much liberty than to those attending too small a degree of it.’

More than 30 years after Jefferson’s death in 1826, John Stuart Mill – whose prescient quote at the top of this piece could almost have been written last month – grappled with the difficult business of freedom and the good society in his great text, On Liberty.

‘Social tyranny’

He recognises the force of what he calls ‘social tyranny’ – Azmanova mentions this, too – which is ‘more formidable than many kinds of political oppression, since, though not usually upheld by such extreme penalties, it leaves fewer means of escape, penetrating much more deeply into the details of life, and enslaving the soul itself’.

He argues: ‘There is a limit to the legitimate interference of collective opinion with individual independence: and to find that limit, and maintain it against encroachment, is as indispensable to a good condition of human affairs, as protection against political despotism.’

Setting such a limit is predicated on the certainty of that ‘quality of the human mind, the source of everything respectable in man either as an intellectual or as a moral being, namely, that his errors are corrigible’.

But for ‘wrong opinions and practices’ to ‘gradually yield (in the mind) to fact and argument’ means ‘facts and arguments … must be brought before it’.

Mill goes as far as recommending that even if ‘opponents of all important truths do not exist, it is indispensable to imagine them, and supply them with the strongest arguments which the most skilful devil’s advocate can conjure up’.

‘The fatal tendency of mankind to leave off thinking about a thing when it is no longer doubtful,’ he cautions, ‘is the cause of half their errors. A contemporary author has well spoken of “the deep slumber of a decided opinion”.’

No liberal celebrated Jon Qwelane’s egregious column of 2008, yet welcomed the opportunity to challenge it.

The strength of the best, the kindliest, the most fruitful ideas is not that they enjoy approval, but that they can demonstrably withstand contradiction. Which is why they must constantly be put to the test.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend