This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

19th August 1745 – Prince Charles Edward Stuart raises his standard in Glenfinnan: The start of the Jacobite Rebellion, known as “the 45”

During the 17th century, England, Scotland and Ireland, who shared the same king, were torn apart by internal conflicts, culminating in the English Civil War, which saw the Kings of the British Isles driven into exile in France and the ‘Lord Protector’ Oliver Cromwell assume control over a new ‘Commonwealth’.

Shortly after Cromwell died, the Commonwealth collapsed in 1660, and the English invited the son of their deposed king, Charles II, back to rule England. The war had strongly changed the balance of power between king and Parliament, conflicts over which had dominated English politics for centuries. Now Parliament saw itself as largely superior to the king and expected him to acknowledge this fact. This did not last and later in Charles’s reign, king and Parliament began to squabble with each other once again.

As Charles grew older, there was growing concern in his kingdom about his heir, James II, who was a Catholic. Many of England’s wars of recent decades had been against powerful Catholic nations, and in the minds of many Britons Catholic kings were synonymous with tyranny, as Catholic monarchs in Europe, such as In France, had used religion as part of the justification of their ‘divine right to rule’.

In 1685, Charles died, and James II became king of England, Scotland and Ireland. Within a year he began to alienate his supporters, who had backed him in the hope that he would help stabilise the country. He in fact destabilised the political situation by suspending Parliament and ruling by decree – this, because Parliament had refused to pass legislation he favoured, such as repealing restrictions on Catholics and non-conforming Protestants. James maintained control for a short time. However, as his heir was his daughter, Mary, a Protestant, and since James was fairly old, many believed he would soon die and the throne would pass back to a Protestant who would respect the political rights of Parliament.

This idea was shattered when James’ wife gave birth to Prince James Francis Edward Stuart in 1688, displacing Protestant Mary as the heir and seeming to establish a Catholic dynasty, which the English feared would destroy the political freedoms hard won in the years of civil war.

In the same month as the birth of his son, James had placed several bishops on trial for defying him; they were acquitted of the charges on 30 June and, in the aftermath, the king’s authority collapsed.

A rebellion sprang up, the rebels inviting Prince William of Orange, the ruler of the Netherlands, and husband of James’ Protestant daughter Mary, to assume the throne of England.

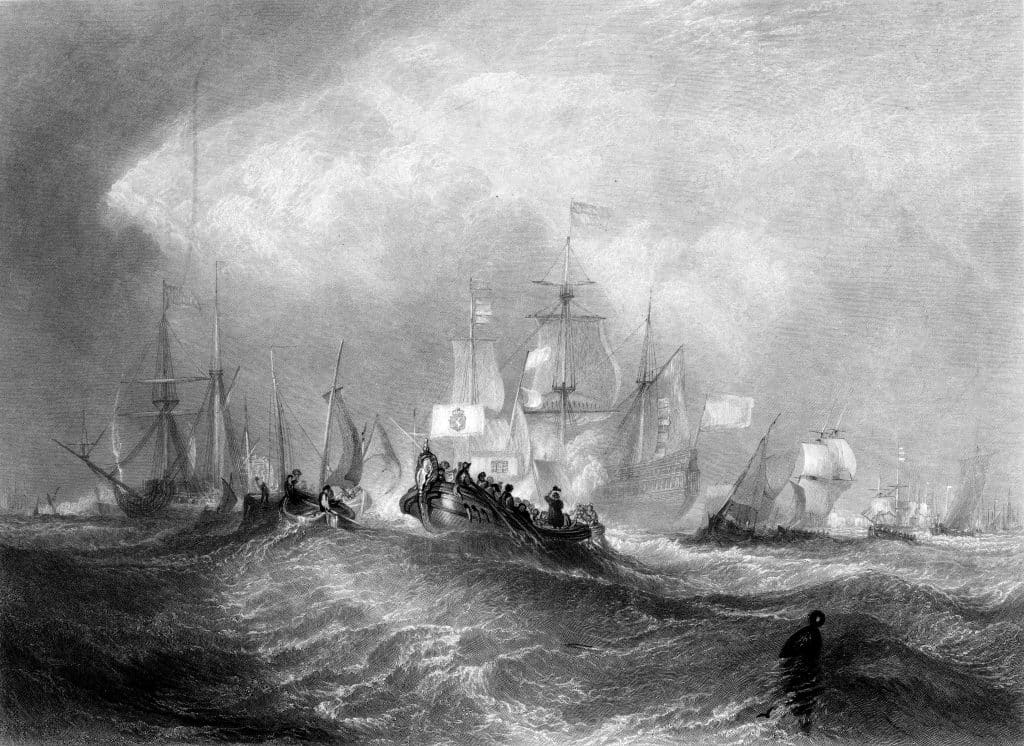

William had been planning an invasion for some time now and by the end of 1688 had landed in England with 35 000 men, declaring that ‘the liberties of England and the Protestant religion I will maintain’. Most of the Protestant officers in King James’ army defected to the Dutch and James was soon forced to flee the country without putting up much of a fight.

William and Parliament entered negotiations and in 1689 declared William and Mary joint monarchs of England, with William being the senior monarch. William also approached the Scottish Parliament and managed to win a majority of MPs to his side by being more conciliatory, whilst James made demands that the Scots support his attempts to be restored to the English throne.

The event became known as the ‘Glorious Revolution’; the political rights and freedoms it enshrined in the English political system, such as the superiority of Parliament and a distaste for tyranny, would later inspire the American Revolution in 1776.

William was soon forced to face revolts to his rule in Ireland and Scotland. In many parts of the British Isles, many people continued to believe that the king’s right to rule derived from God, and therefore Parliament was acting illegally by deposing King James. These people, known as Jacobites, would launch several rebellions to restore James and his heirs to the throne of England, Ireland and Scotland.

Jacobite rebellions would break out in 1689, 1708, 1715 and 1719. All were put down by government forces.

In 1745, Charles Edward Stuart, the grandson of James II, left France –where he had been gathering support to restore himself and his father to the throne – and landed in northern Scotland where he joined with Scottish Jacobites on 19 August 1745.

In September, Charles captured the capital of Scotland, Edinburgh, and had his father proclaimed king of Scotland. In an attempt to win more Scottish support, he also declared the dissolution of the Union of the crowns of England and Scotland that had occurred in 1707. With a fresh delivery of French arms and money in October 1745, the Jacobites marched south into England, hoping to be joined by English Jacobites.

While the Jacobite army got as far south as Derby, they were not joined by as large a number of English supporters as they had hoped, and as government armies advanced on their position and French reinforcements arrived in Scotland, the Jacobites decided to retreat to Scotland again. In December 1745, the Jacobites re-entered Scotland, and in January of 1746 they clashed properly with government troops at Falkirk Muir.

The Jacobites managed to win a victory but failed to follow it up and destroy the government force they had routed. In April 1746, the Jacobite army of around 7 000 troops faced off against a government force of 8 000 in the Battle of Culloden in northern Scotland, and were soundly defeated.

After the defeat, the Jacobite movement largely collapsed, and there were no more major Jacobite uprisings after 1746.

Charles Edward Stuart attempted to keep his cause alive, even secretly returning to England in 1750 and converting to Protestantism to make himself more acceptable to the British. This achieved little, and although he attempted to win French support for an invasion to place him on the throne, he left a bad impression on the French officials.

When his father died in 1766, Charles was not declared King of England by the Pope, as his father had been, and this further hurt his cause. He died in Rome in 1788 after legitimising his illegitimate daughter as his heir. However this process could not pass the claim to the throne to her and only offered her rights to his property. So died the Stuart kings of the British Isles.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend