The last-resort answer to almost any discussion on environmental sustainability, poverty or unemployment, is to claim that the real problem is overpopulation. It isn’t.

‘The world population is growing faster than the availability of resources.’

‘Currently the population growth is out of control.’

‘Malthus is back. Exponential population growth combined with unregulated rapacious capitalism and consumerism together with the extraction of finite resources is of course unsustainable.’

‘A virus like Covid19 and a nuclear war will be the solution to overpopulation, economic stagnation and state control.’

‘Why is nobody discussing the population growth problem?’

These are just a few of the comments I received on my recent columns. Okay, so let’s discuss the supposed population growth problem.

If you gather the entire world’s population of 7.9 billion people in one place, and make them stand shoulder to shoulder, they would just about cover the State of Palestine, or Puerto Rico. If you tell them to observe two-metre social distancing in all directions, they would fit into the Free State.

The global average household size is 4.9. If you gave each family an acre for a food garden, you could easily fit the entire world population into Australia. If you gave everyone their own acre, you’d fill Russia, China, India and Pakistan, leaving four fifths of the world entirely empty.

About 55% of the world’s population presently live in urban areas, which in turn account for between 1% and 2.7% of the Earth’s land surface, depending how it’s measured and who does the measuring.

The numbers

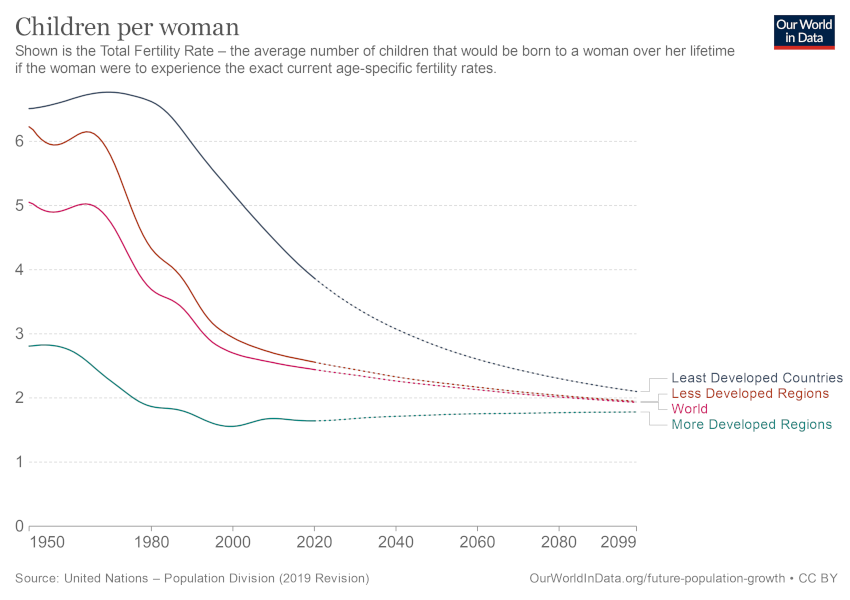

Average global fertility, that is, the number of children born per woman, has decreased from a peak of 5 in the 1960s to 2.5 today. This decline is visible in all countries, at all poverty levels.

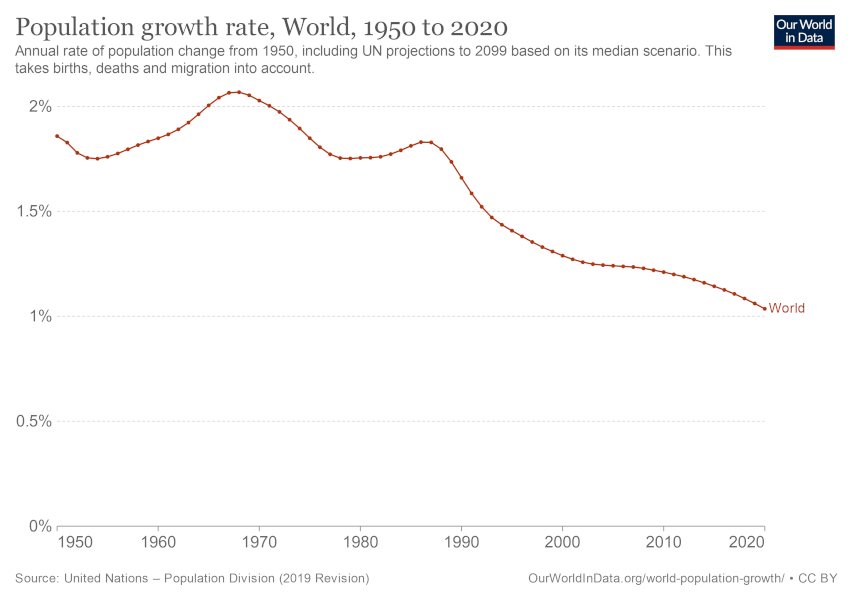

The global population growth rate, which is a function of both births and deaths, peaked north of 2% in 1968, and has steadily declined to a shade over 1% today.

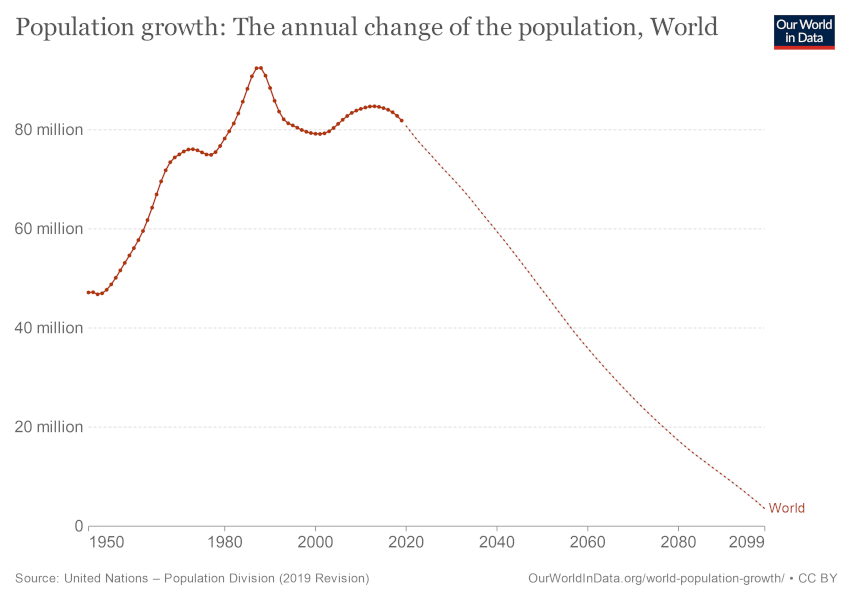

In absolute numbers, global population growth also peaked, back in 1988.

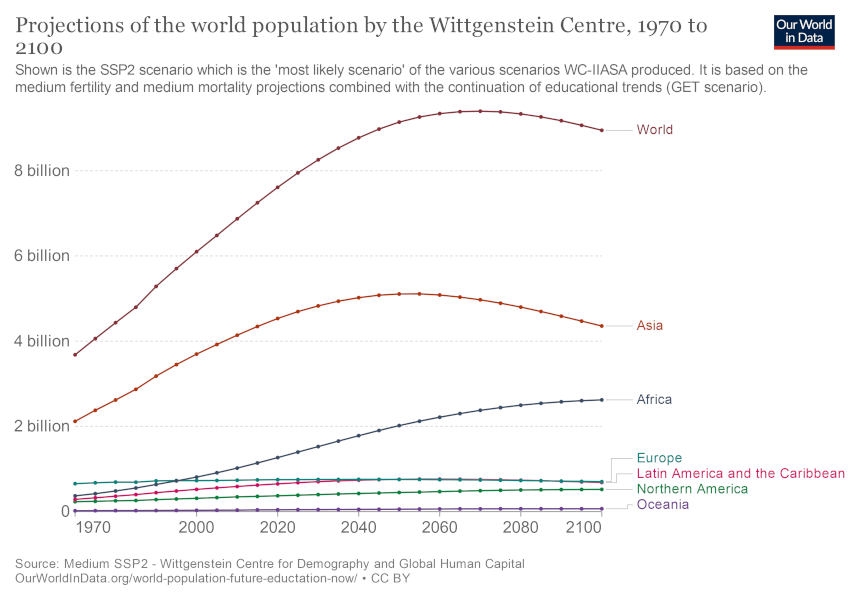

A projection of the global population size, disaggregated by continent, based on medium-case assumptions for fertility and mortality, shows that the population will peak below 10 billion around 2070, and begin to decline naturally after that.

So far, then, we’re not heading for a crisis. It seems population growth will look after itself.

Food and resources

The next question, then, is whether we’re running out of resources, and in particular, whether we’re running out of food. If this were true, we’d expect that the total land under agriculture would be increasing, to keep pace with the world population. As it turns out, thanks to improved farming methods, this is not true.

Almost a decade ago, researchers led by famous environmental scientist Jess H. Ausubel said: ‘…we believe that humanity has reached Peak Farmland, and that a large net global restoration of land to Nature is ready to begin.’

I wrote about their paper at the time, saying feeding the world is getting easier.

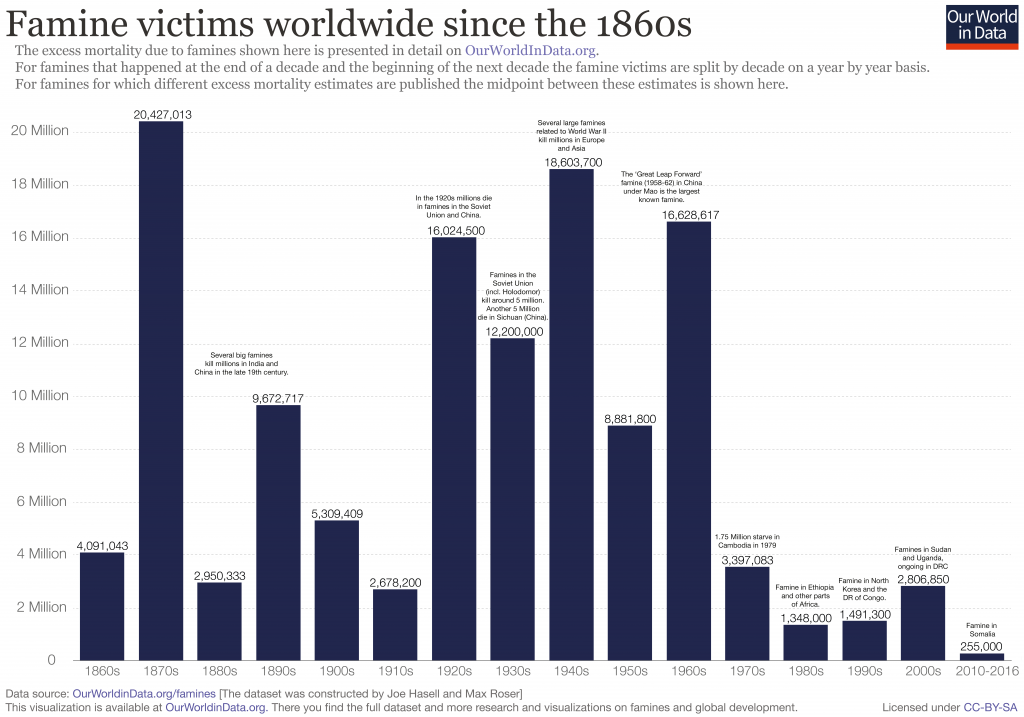

To underscore the fact that the world’s population is not outstripping the availability of food, one only needs to look at the history of famines over the last century and a half. Since the 1970s, the absolute number of people killed in famines has shown a sharp improvement, and the remaining famines are limited to countries that are at war, or are hopelessly governed.

I’ve covered the mistaken notion of resource depletion in previous columns, so I won’t belabour the point here. Suffice to say that between innovation, substitution and conservation, we won’t run out of resources in the foreseeable future.

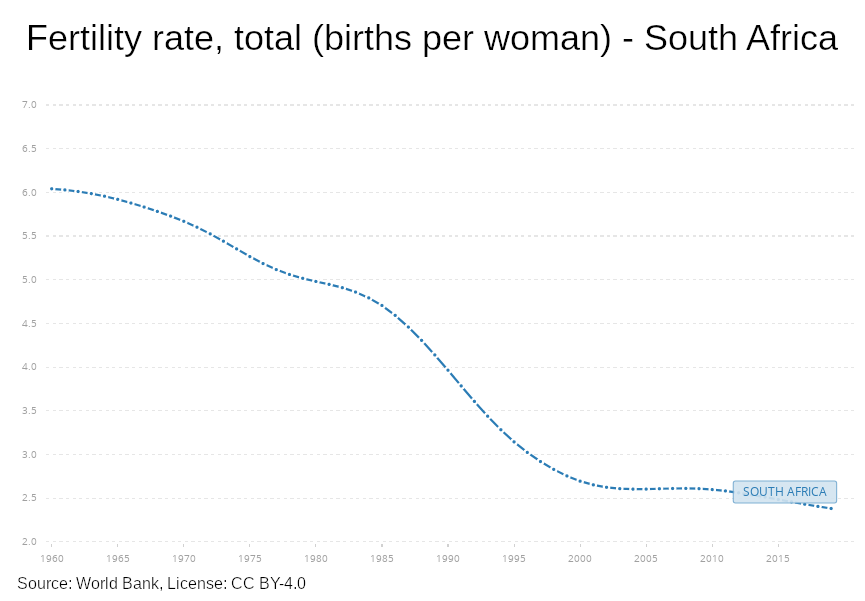

Is the picture any different at a local level? Back in 1960, the fertility rate in South Africa was a hefty six births per woman. That has declined steeply to a rate of only 2.4 births per woman in 2019.

There is also no sign of a crisis in agricultural output in South Africa. Poverty is a problem, and food distribution might be a problem, but the old Malthusian equation of exponential population growth versus linear food resource growth has not reared its head in South Africa.

Population control

One wonders, then, why the population growth bogeyman, and the concomitant population control mantra, remain so loud.

Fears about population growth were first raised by John D. Rockefeller III, the grandson of the man who created the Rockefeller Foundation. He established a separate entity, the Population Council, to research population growth and population control strategies, with support from the Rockefeller, Ford, Mellon, Hewlett and Packard Foundations.

As a result, by the time the first popular concern about population growth was raised in the 1960s by doom-mongers like Paul Erhlich, a generation of trained demographers was already in place to provide information and policy direction to governments.

Ehrlich predicted mass starvation in the 1970s and 1980s. This never happened, but Ehrlich remains unrepentant, believing that the collapse of civilisation will vindicate him any day now.

The United Nations got on board, holding several population conferences focused first on studying, then on limiting, population growth.

John Holdren was a protégé of Ehrlich’s who later became US president Barack Obama’s chief scientific adviser. With Ehrlich and his wife, Anne, Holdren penned a book entitled Ecoscience: Population, Resources, Environment, in which the trio fantasise about forcible sterilisation, issuing licences to have children, and even adding sterility-inducing drugs to the water or food supply.

Of these measures, Holdren et al. Wrote: ‘…some countries may ultimately have to resort to them unless current trends in birth rates are rapidly reversed by other means.’

A multitude of organisations contributed to the literature about ‘population control’, a subject which is as tyrannical as it sounds.

Population control lobbying groups like Zero Population Growth and Optimum Population Trust have adopted less severe-sounding names, Population Connection and Population Matters, respectively. However, they still worship Malthus and Ehrlich to this day, and advocate for strict population control and not having any children.

Despite their extremist objectives, they attract heavy hitters like David Attenborough, who says: ‘All our environmental problems become easier to solve with fewer people, and harder – and ultimately impossible – to solve with ever more people.’

They have developed teaching materials and lesson plans to indoctrinate children about the evils of having children. How sad is that?

One-child policy

Population control, where it was implemented, has had severe consequences.

China imposed a two-child policy in 1970, and a one-child policy in 1979. Many Western elites praised China for its foresight and envied it for its ability to impose such population control measures.

There were many official exceptions to the rule, and many unofficial transgressions, but between 1979 and 2010, China’s fertility rate dropped from 2.8 births per woman to 1.5. In 2015, China repealed the one-child policy and returned to the two-child policy of pre-1979.

The policy led to gross human rights violations, however. Because married daughters owed their support to their in-laws, and not their own parents, many Chinese parents, especially in rural areas, abandoned daughters born to them, chose sex-selective abortions, or committed infanticide, in the hope of bearing a boy instead. Implementing the law and fining parents who had unauthorised children also led to much coercion and abuse. Parents who could not afford the fines were forced to abandon their children, because the state refused to register them as part of a family, so the excess children would grow up as orphans without any education.

China’s one-child policy also led to a significant skew between male and female population, a rapidly ageing population, and poor financial support for the elderly, especially in rural areas.

Eugenics

The wagging fingers of the population alarmists were typically raised against the peoples of Africa and Asia. Not long before Rockefeller began to focus on population control, the eugenics movement had fallen out of favour, thanks to Hitler’s attempts to build a pure Aryan race.

The idea of eugenics, a movement which was very popular among pre-war progressive elites on both sides of the Atlantic, was to assume technocratic control over the population to make sure that human populations did not grow out of control. It also sought to ensure that the human population would be improved by planned selection rather than degenerating through uncontrolled procreation.

Targets for sterilisation included ‘backward’ and ‘degenerate’ peoples, including entire races that were supposed to be inferior, as well as people of feeble mind or with congenital conditions such as epilepsy. The Fabian socialists in Britain railed against what they called ‘unemployables’, and included in the ranks of the inferior people who worked for wages lower than the reformers deemed worthy. Also targeted were immigrants, alcoholics, smokers, and slackers.

Despite Hitler’s best attempts to give eugenics a bad name, some eugenic impulses persist in the modern world. Even in developed countries, there have been several attempts, some successful, of prohibiting certain classes of people from procreating.

In the Netherlands, a petition was submitted to parliament that would force women deemed unsuitable for parenthood due to addiction, mental health, or mental disability to receive a mandatory injection or contraceptive implant to prevent pregnancy. It failed.

Poland passed a law in 2009 under which convicted child sex offenders would be chemically castrated. At the time the law was being discussed, the country’s prime minister said: ‘I don’t think you can call such individuals – such beasts – human beings. I don’t think you can talk about human rights in such a case.’

It is easy for a populist to exploit the universal lack of sympathy people have for such offenders, but withdrawing human rights, and even humanity itself, from certain classes of criminals sets a very dangerous precedent.

In 2009, a mayor in New Zealand reportedly said: ‘…it would be far better for this appalling underclass to be offered financial inducements not to have children, given the toxic environment that they would provide for any child in their care.’

New pretext

For the most part, however, the technocrats and bureaucrats needed a new pretext for their fantasy of population control. Fears of running out of resources and environmental problems offered just such an excuse.

With explicit discrimination against people based on innate characteristics having fallen out of favour, the new eugenicists simply use poverty as a proxy.

The poor generally have more children than the rich. Reasons include higher child mortality, the need for more breadwinners in the family, and the need for family-based elderly support in the absence of formal pension arrangements.

As people and societies get more prosperous, all of these motives for having larger families fall away. That means that there is no need to limit the population.

Free the markets

Ultimately, whether a society suffers from overpopulation is entirely dependent on its economy. As we saw from the famine statistics, modern famines are rare, but when they occur, they do so in countries that are at war, are corrupt, or are run by socialists.

Almost by definition, a country without enough food is over-populated. That doesn’t mean that the population needs to be cut, however. It means that the economy needs to be set free – free from needless regulations, ill-considered government intervention, and excessive taxes – to encourage production and prosperity growth.

In a growing society, every new member adds to the potential prosperity of the country. Every new child becomes a new adult, bringing new labour, new ideas, and new vitality to the economy.

Overpopulation, seen through this lens, is not a ‘problem’ in itself that needs to be addressed through cruel and autocratic control. Rather, it is a symptom of failing economic policies.

The answer to creating a sustainable world fit for both existing and future generations lies in economic freedom. As I wrote a couple of years ago, economic freedom will save the planet.

Beware of people who raise the spectre of overpopulation, and show a desire for population control. Their reasoning is false, their instincts totalitarian, and their motives very likely based on prejudice. Beware the new eugenicists.

[Image: Vania dos Santos vvaniasantoss from Pixabay]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend