This is the third in a series of five articles on the topic of federalism in South Africa, past, present, and future. Each article may be read as a standalone piece, but they are best read chronologically.

When the transition out of white minority rule in South Africa began in earnest – one can speculate as to when this was, but for present purposes it is regarded as State President FW de Klerk’s unbanning of the African National Congress (ANC) in February 1990 – almost at once authoritarian leftists began accusing federalists of wishing to retain Apartheid in practice if not in principle. This opportunistic line (purposefully) ignored the entire history of the federal movement in South Africa.

The ANC, at least since the 1950s, had shunned federalism. Under the guidance of their socialist ideology (which would have revolted the pre-1950s ANC), any decentralisation was regarded as taking resources away from the centre. This would undermine the central government’s ability to control all the levers of power and direct society according to its whims, to the ultimate end of achieving the National Democratic Revolution.

ANC thinkers, in other words, were deathly afraid of federalism, precisely because it would serve its main function: the counteraction of centralised authority. They therefore took a naked desire for control and rationalised it into something more palatable for public consumption. Two notable thinkers in this respect were Albie Sachs (later a Constitutional Court justice) and Kader Asmal (later a minister and academic).

Asmal, in his contribution to South Africa’s Crisis of Constitutional Democracy: Can the U.S. Constitution Help? (1994), channelling his inner Merriman and Smuts, almost verbatim repeated what the old statesmen of Union had said against federalism, when he wrote that placing too many limitations on the central government and empowering regional governments ‘is a recipe for constitutional immobility and constitutional warfare.’ His addition to Merriman’s and Smuts’ arguments, was the ANC line that federalism would ‘lock’ wealth into certain provinces, which would also abuse their ‘veto’ to stop any centralist redistribution schemes. This was a ‘recipe for the entrenchment of segregation and privilege.’ Asmal argued that the economy must be subject to ‘central management’ and that the central government have a free hand in its ‘reconstruction of the country.’

Sachs, writing earlier in his Protecting Human Rights in a New South Africa (1990), likened federal ideas at best to ‘hidden or democratic apartheid’ or at worst to ‘multiracial apartheid.’ Both would unacceptably stand in the way of unqualified majority rule and ‘rapid moves to end the inequalities produced by apartheid.’ Sachs supported the approach of the Freedom Charter (1955): ‘the only effective and lasting way to dismantle [Apartheid] is to establish a non-racial, non-sexist, democratic society in a united country.’

He toned down this line in his later Advancing Human Rights in South Africa (1992), but clung to the idea that federalism would, rather than ‘promote liberty,’ rather ‘consolidate autocracy,’ and thus proposed that regional governments should rather focus on implementing national policies, and whenever there is a conflict between the centre and the regions, the centre should have ‘the last word.’ Sachs was here endorsing the German system of ‘cooperative federalism,’ which will be returned to in the next article.

The promise

Sachs and Asmal – certainly among others – made the assurance that a supreme constitution, a justiciable bill of rights, and an independent court system would protect minorities and individuals from abusive government. Sachs even added that we would have a Public Protector (‘office of ombud’) and ‘a human rights commission’ to protect against violations of rights – how lucky we are indeed!

There was no need, the ANC’s spin-doctors argued, to retain the façade of Apartheid with real federal decentralisation, and in fact this would undermine national unity and reconstruction. The central government will be constitutionally limited, and regional governments would receive an appropriate amount of power devolved at the discretion of the centre.

As Merriman had thought almost a century earlier, so too did Sachs and Asmal essentially argue that federalists and cynics should trust in the power of democracy, and have faith that their fellow countrymen would not allow a tyrannical regime to become entrenched in power. Writing around the same time, Donald Horowitz in A Democratic South Africa?: Constitutional Engineering in a Divided Society (1991) sagely noted that ‘federalism generally remains only the wisdom of hindsight in Africa.’

The Nats’ weakest moment

Except for a few confused Africanists, who believe the ANC and broader liberation movement were misled and made fools of during the transition, it seems to me to be widely agreed that the NP and ANC were either firm coalition partners during the transition or the NP was taking its instructions from Luthuli House. Roelf Meyer, the NP’s chief negotiator, did not do anything without glancing in the direction of Cyril Ramaphosa, the ANC’s chief negotiator, for an approving nod.

For a very brief moment in 1991, when the NP adopted ‘Constitutional Rule in a Participatory Democracy’ at its Federal Congress in Bloemfontein, it was a federalist party, but again in fine NP tradition not employing the word ‘federalism’ or ‘federation’ anywhere. The proposal was not very detailed, but some highlights bear mentioning.

In this policy programme, the NP proposed the current nine provinces that comprise South Africa. It also proposed the constitution of the National Council of Provinces more or less as we know it today (gee, thanks for nothing!). The provinces (or ‘regional authorities’), however, would not merely be decentralised extensions of the central government, but governments with constitutional authority in their own right. In particular, they would have their own tax bases.

The NP’s real federalist impulse however shone through with its proposals for local government. In addition to vesting municipalities with constitutional authority (an idea that survived the transition and is unique in South Africa), the NP also proposed governance structures at the neighbourhood level. So-called ‘neighbourhood councils,’ which very local communities could decide voluntarily whether or not to establish, would be empowered to regulate ‘norms and standards for the residential environment,’ property use licences and permits, the provision of ‘communal facilities,’ security and ‘civil protection,’ and certain education and welfare matters assigned by national legislation. These councils would be funded by levies charged on neighbourhood residents.

When it comes to the principles the NP supported for the national executive authority, and which it argued should be applied in a similar way to provincial executives, it is clear that the KwaZulu/Natal Indaba did leave an impression on the party that firmly rejected its proposals only five years prior.

The Nats proposed that that South Africa’s executive consist not of one party, but of all the ‘major parties.’ A collective body known as ‘the Presidency’ should be established that would be composed of the leaders of the three largest parties represented in the National Assembly, with the chairmanship of the Presidency rotating between them annually. All decisions, including ministerial appointments, were to be taken by consensus. A (presumably ceremonial) State President could be elected from the Presidency, also on a rotating basis.

For a brief moment in the early 1990s, then, the NP adopted federalism as a policy proposal for the new South Africa. This put the NP in the same camp as the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) and the Democratic Party (DP, successor to the Progressive Federal Party).

As James Hamill wrote in 2003, the NP’s less than sincere adoption of federalism appears to have harmed the idea itself in the public consciousness. Immediately, many people thought the NP was trying to hang onto power indirectly. The IFP and DP, of course, had always opposed the NP’s policies and were committed federalists.

Amusingly, but also dishearteningly, the NP dropped federalism almost as quickly as it picked it up, with ‘Constitutional Rule in a Participatory Democracy’ virtually never being heard of again. During the negotiations, the NP allowed the ANC and its partners to get their centralised state apparatus without too much of a fight, in large part (it is submitted) because of the rush the NP was in to conclude the process, discussed below.

When the NP (re)joined the ANC’s centralist ranks mere months after coming out as federalists, there was not a similar visceral reaction. In other words, while the NP becoming federalist damaged the federal cause, the NP becoming centralist did not damage the centralist cause. The critics of federalism today would tell you that federalism is an NP-inspired tactic to perpetuate Apartheid, without paying too much attention to the fact that the NP in fact ended up supporting the very centralism that has played a considerable role in keeping millions poor.

The haste of the transition

South Africa’s transition out of Apartheid was undertaken with a large degree of haste. It is certainly true that no system of oppression should be kept alive simply because political elites are taking their sweet time ironing out small details, but such a concern was not applicable to South Africa in the few years prior to 1994. Virtually every Apartheid law that had survived State President PW Botha’s underrated reforms of the 1980s, had been or was in the process of being repealed. In other words, for the constitutionally-minded, there was no good reason to rush.

For the politically-minded, however, there was every reason to rush, and this haste had very real consequences with which we are still saddled today. These consequences will be discussed in the next article.

The NP’s eagerness to bring a speedy end to the transition was entirely opportunistic and not motivated by any lofty humanitarian considerations. Since the late 1980s, a very troubling reality was manifesting itself to the reformist Nats: The Conservative Party (CP), the official opposition that for the first time in half a century sat to the right of the governing party, was on the verge of an electoral victory.

The CP had been taking NP seats in multiple by-elections since the 1989 general election in which it became the official opposition, and there was a belief that if another whites-only general election were to be held, the CP would win.

The growing support of the CP should not be construed as growing white opposition to reform. The reformist PW Botha was not abandoned by his electorate, and the 1992 referendum cleanly showed that a comfortable majority of whites sought some kind of reform. This might, however, simply not have been the kind of reform the NP had in mind. And the CP itself did not propose to retain Apartheid as it then stood – its reform programme was admittedly more equivocal and messier, but everyone except a literal handful of hardliners by the 1990s knew Apartheid was over.

Witnessing the CP’s rise dismayed the NP. If the CP continued to take seats in by-elections, it might soon displace the NP as the chief government negotiating party at the bargaining table, and rob the NP of its sought-after power-sharing arrangement with the ANC. The Government of National Unity was to be the start of this phenomenon.

The assumption in NP circles was that, with the dawn of non-racial democracy, it would enter the new government as the second largest party after the ANC, but still the senior partner. Its many years of experience, its influence in the civil service and in the armed forces, and its expertise in governance, would entrench it as the strong national movement it was many years ago. It would be the regent to the infant ANC, moulding it, and pulling many of the strings. As we now know, this was a pipedream.

With every seat the Nats lost in Parliament, and with the prospect of potentially losing a majority of seats if another whites-only election took place before the transition was concluded, the NP was in a great rush. There was no time to be bittereinders at the negotiating table – if they saw the ANC would not budge on something, they conceded.

Last hurrah of competence in the ANC

The ANC was well aware of what was happening in the ranks of their opponents. It was playing its own game. It created the impression that it was also in a rush, but in fact the ANC was biding its time. With a unified, centralist voice, not nearly as equivocal or uncertain as the NP, the ANC had quite a good grasp on how events would play out going forward. There was real, long-term thinking, and political genius among the ANC during the transition, hardly comparable to the Bheki Celes and Fikile Mbalulas of today who make it difficult for us to discern whether they are jokers or simply brainless.

Unfortunately, the ANC’s genius was employed for a bad cause.

The ANC, of course, could not show all its cards. It knew it would soon control the police, military, judiciary, and tax collection, but it had to act like it was engaging in good faith. It gave the NP certain concessions that it knew it could easily reverse later. But it also had to put up a façade of concern – concern about how people were suffering, and thus that the NP’s minority rule must be immediately brought to an end. This, no doubt, did not only make things difficult for people in the NP but also in other negotiating parties like the IFP and DP.

In his book, Endgame, and the film of the same name, Willie Esterhuyse, who was part of a contingent of Afrikaner academics who met with the ANC and brokered dialogue between them and the NP in the late 1980s, outlines the sense of urgency he saw from Thabo Mbeki, later President of South Africa. The line Mbeki’s actor, Chiwetel Ejiofor, spoke to Esterhuyse’s actor, William Hurt, in the film, has stuck with me since I saw it some years ago: ‘Time is the enemy.’

It does not appear that Mbeki in fact uttered these exact words, judging by the book. It is more likely that the filmmakers used this pithy line to summarise the various instances of Mbeki’s and his colleagues’ manifest haste, particularly at the fifth meeting of the ‘Afrikaner-ANC dialogue group’ at Mells Park between 21 and 24 April 1989.

Senior ANC executive Aziz Pahad explained that the ANC leadership was aging, and a new band of leaders would soon come about. When FW de Klerk would succeed PW Botha and thus begin formal negotiations was therefore an important event that the ANC could not wait for forever.

Later, after Willem de Klerk (FW’s brother) and Esterhuyse set out a potential timeline of around six months, Esterhuyse noted that it seemed like Mbeki’s ‘hope for the future’ sunk away. Mbeki is reported to have told Esterhuyse, ‘How long do you think we have to wait? Patience has limits.’ In a private conversation later between them, Mbeki appeared more positive, saying that it seemed things would pick up speed once FW became State President.

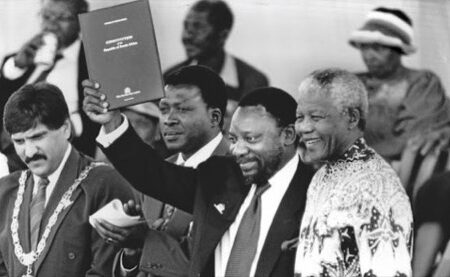

By February 1990, FW announced the unbanning of the ANC and other organisations, and released political prisoners like Nelson Mandela. Two years later, a referendum that caught the CP and its associates entirely off guard while they were riding the crest of their political wave was announced and held. Less than a year thereafter, in 1993, the interim Constitution was adopted, solidifying the extant composition of the white Parliament until a non-racial election was held on 27 April 1994.

In many ways, the real negotiations only took place between December 1991 and November 1993 (when the negotiating parties agreed to a draft of the interim Constitution) – less than two years. This is because the interim Constitution contained a list of non-negotiable principles that would have to be recognised in the permanent (current) Constitution that was debated by the Constitutional Assembly after the 1994 election and adopted in 1996. If you did not get your principle in that list during those two years, it would almost certainly not show up in the current Constitution.

Thankfully, federalism made the cut in all but name. Principles 16 to 27 (of 34 principles) were all about the constitutional entrenchment of a vertical separation of powers, something that is characteristic of a federation. How the federalisation of South Africa during the transition turned out for us today is considered in the next article.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend