Allegedly, radiation levels at an abandoned mine in Krugersdorp are ‘similar to … Chernobyl,’ and local people eat radioactive waste. So reports Angus Begg for Daily Maverick. Let’s get some perspective.

I have long argued that environmental exaggeration is routine among eco-activists and their credulous, sensationalist media transcribers. I also believe it harms countries – especially poor countries. It undermines cost-benefit analysis of environmental policies and projects. It encourages regulatory over-reaction. It prevents proper prioritisation of limited resources.

I even wrote a book about it. If everything is a deadly crisis, then every problem must be addressed without delay, no matter the cost. Nobody can manage the environment, or anything else, in that sort of rhetorical climate.

For example, if we really have a Chernobyl on our doorstep, as Angus Begg claims in the Daily Maverick, we should probably drop everything and throw what little resources the country has left at remediating this crisis.

Aside from radiation levels ‘similar to that found after the explosion and meltdown of Chernobyl, the Soviet nuclear power plant, in 1986’, people are actually eating radioactive waste, according to veteran environmental activist Mariette Liefferink, quoted in the article.

‘It’s called pica,’ she told Begg, adding that, ‘Eating or ingesting soil is a common practice among children and pregnant women.’

Thus, suitably shocked and horrified, we are primed to accept Begg’s narrative, which is largely based on Liefferink’s decade-old fallout with the National Nuclear Regulator (NNR), and her accusation that it does not do enough about people living on or near the remaining mine dumps and tailing dams of long-abandoned mines, which contain toxic chemicals and low-grade radiation.

Tudor Shaft

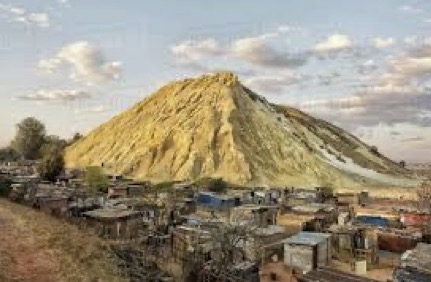

The particular site on which Begg and Liefferink hang their story is Tudor Shaft. It isn’t marked on either Google or Bing maps, and the Environmental Justice Atlas has it located near Slovoville in Soweto, which is clearly wrong. It seems to involve the shacks on this old mine dump site in Witpoortjie.

According to the story, an informal settlement was established 25 years ago on an abandoned mine dump. Many of its residents appear to have been moved to a nearby low-cost housing development, but 18 people refused to move, because they were rather particular about where they were getting moved to.

These, then, are the people allegedly exposed to the grave dangers of the mine dump.

Because gold mines often contain uranium, the tailings disposed of on mine dumps are indeed slightly radioactive. But does the comparison with Chernobyl hold up?

The claim of radiation levels ‘similar to that found after the explosion and meltdown of Chernobyl’ is based on a claim by the water management expert and professor at the University of Free State’s Centre for Environmental Management, Anthony Turton.

In a talk given in 2010, he reportedly said of the Tudor Shaft settlement: ‘The risk is of radiation exposure at levels ranging between 8mSv [milliSievert] in their homes, and 15mSv/yr [milliSievert per year] if they should venture to the Tudor Dam, a place where children play. For those living in the Chernobyl contaminated areas, but not evacuated, the radiation level was 9mSv.’

Hence the claim that the exposure levels were ‘roughly the same’. But were they, really? Let’s dive into the weeds.

Turton’s claims about Tudor Shaft radiation levels are inconsistent with the findings of a 2010 survey conducted by the NNR, as reported by the World Information Service on Energy, an anti-nuclear lobby group. It measured the dose at the Tudor Shaft settlement to be a mere 3,9mSv/yr – less than half the dose reported in that same year by Turton.

That link includes many more details about the Tudor Shaft case, which are hard to reconcile with the facts stated in Begg’s article. But let’s be generous, and accept the veracity of the 8mSv/yr claim.

Chernobyl

Turton is correct about the radiation exposure of non-evacuated residents of contaminated areas around Chernobyl, however.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) reports: ‘The average effective doses among 530,000 recovery operation workers was 120 millisieverts (mSv); among 115,000 evacuees, 30 mSv; among residents of contaminated areas, 9 mSv (during the first two decades after the accident); and among residents of other European countries, less than 1 mSv (in the first year after the accident).’

Of course, the fact that non-evacuated residents were not evacuated strongly suggests that the dose to which they were exposed was not believed to be substantially harmful. This would imply that the levels at the Tudor Shaft settlement aren’t particularly alarming, either.

A Sievert doesn’t actually measure ‘radiation levels’, but rather, the probable health risk due to exposure to various kinds of radiation over time. The unit is only used for low-level radiation; it is never used for significant levels of radiation that are known to cause short-term harmful effects such as radiation burns.

Turton conflates mSv and mSv/yr (or perhaps he was misquoted). The first measures a total effective dose, and the second a dose rate over time. I’m going to gloss over this, and make the most conservative assumption, namely that the 8mSv (Tudor Shaft), 9mSv (Chernobyl) and 15mSv (Tudor Dam) values are all dose rates per year.

Actual risk

The health risk due to 1Sv of radiation, received over an extended period like a year, is a 5.5% chance of eventually developing fatal cancer. (A 1Sv dose received in a short time can cause symptoms of radiation poisoning.)

This risk is based on the linear no-threshold model, which is a widely-used but contested model. According to this model, there is a linear relationship between radiation dose and the risk of physical harm (primarily cancer), no matter how small the dose is. In the case of low levels of radiation, it is a worst-case scenario model, so let’s suppose it to be valid, again for the sake of conservative estimates.

If 1Sv causes a 5,5% chance of fatal cancer later in life, and we use a linear model, we conclude that 8mSv causes a 0,044% chance of fatal cancer, or one in 2 273. For the NNR’s estimate of 3,9mSv, it’s 0,021%, or one in 4 662. While this is not insignificant, it is hardly the stuff of nightmares.

On the legendary xkcd radiation chart, you’ll see that a chest CT scan exposes one to 7mSv of radiation, and that the maximum yearly dose permitted for radiation workers in the United States is 50mSv. The lowest annual dose ‘clearly linked to increased cancer risk’ is 100mSv. The dose limit for emergency workers involved in life-saving operations is 250mSv.

By that standard, 3,9mSv/yr, 8mSv/yr, or even 15mSv/yr, is child’s play. All it means is that it might be a bad idea to reside at such a site for decades, for fear of marginally increasing your risk of cancer.

That said, the global average background radiation, estimated to be 2,4mSv/yr by the WHO and 4mSv/yr by xkcd, is not much lower than the 3,9mSv/yr to 8mSv/yr at Tudor Shaft, so really, residing anywhere increases your risk of cancer.

This backgrounder on the biological effects of radiation is instructive. It says the average American is exposed to about 3,1mSv/yr of natural background radiation, and more if they live at high altitudes. Man-made sources add another 3,1mSv/yr, for a total background exposure of 6,2mSv/yr.

So, the 8mSv/yr Turton claims for Tudor Shaft, or the 9mSv/yr for non-evacuated residents of the Chernobyl region, are not much more exposed to radiation than, say, the average resident of Colorado, or indeed, Johannesburg.

Ergo, the comparison to ‘Chernobyl’ is absurd.

By using the very same WHO paragraph, I could argue that even a 1mSv dose is ‘similar to that found after the explosion and meltdown of Chernobyl’, simply by comparing with the exposure ‘among residents of other European countries’.

When the word ‘Chernobyl’ is invoked, it conjures the spectre of deadly radiation exposure near the exposed reactor core, and not the minor levels of exposure to people who didn’t even live close enough to the reactor explosion to be evacuated.

Using ‘Chernobyl’ to refer to doses that are only marginally higher than the natural background radiation is wild exaggeration, which can have only one purpose: to deceive readers and whip up anti-nuclear hysteria.

Inaction?

The gist of Begg’s story is that the NNR has not done anything about the Tudor Shaft settlement. That is wrong, however.

Back in February 2011, Liefferink herself said: ‘It is heartening to report that after more than eight years of whistleblowing, lobbying, thousands of news media reports, hundreds of in loco tours and workshops, and the distribution of hundreds of thousands of pamphlets that the thousands of residents of Tudor Shaft Informal Settlement are in the process of being relocated onto safe land. The National Nuclear Regulator and Mogale City Municipality acknowledged their responsibility in this regard. The relocation was announced yesterday during a meeting with the National Nuclear Regulator.’

At the time, Liefferink sat on the board of the NNR as a civil society representative. By April 2012, however, she had resigned in frustration, claiming that she was not able to raise her concerns.

That same year, the NNR advised the Mohale City municipality to remove the Tudor Shaft waste dump, which they began to do in cooperation with a mining company.

By July 2012, after about half the dump had been removed, the process was halted in its tracks by… none other than Mariette Liefferink. Her environmental group, the Federation for a Sustainable Environment, along with the Socio-economic Rights Institute, were ‘alarmed that it was being done without risk-assessment studies or consultations, and they obtained a court order to suspend it’.

So the whole thing was certainly a mess, but Liefferink had a lot to do with creating it. That supposedly radioactive dump would have been gone years ago, if it hadn’t been for Liefferink’s own obstructionism in court. Meanwhile, Begg accuses the NNR of obstructionism.

If environmental problems actually got solved by the government, how would environmental activists raise funds to keep them in the luxury to which they have become accustomed?

Should the people still living there today be relocated? Probably, yes. The strength of nuclear radiation is inversely proportional to the square of the distance from its source, so even a move a short distance away can dramatically reduce exposure to the uranium in the mine dumps.

Is it the NNR’s responsibility to physically do this? Certainly not. It can only make recommendations against living on mine dumps.

Should the mine dumps be removed and remediated? Ideally, yes. Is that easily done, on sites abandoned by long-defunct mining companies? Certainly not.

When it does get done, should environmentalists stop the municipality? Apparently so.

Hysteria

To add to the ‘Chernobyl!’ hysteria, Liefferink threw in that bit about pica. It is true that pica – the ingestion of material not ordinarily considered to be food – is not unusual. Estimates vary extremely widely (from 8% to 65%), but perhaps a quarter of pregnant women are reported to indulge in these unusual cravings. It has also been reported among children, although its prevalence is unknown.

When Liefferink says ‘common practice’, she is guessing, for dramatic effect.

Pica is a psychiatric disorder, related to obsessive-compulsive disorder. In children, it is often a response to trauma or abuse. In pregnant women, the cause is more likely hormonal.

If there are indeed people living in Tudor Shaft settlement who suffer from pica, they don’t need healthier soil to eat. They need psychiatric treatment. Like everyone else in the settlement, their exposure to dust from the toxic waste dump on which they live will be reduced substantially if they simply agreed to move.

Perhaps Liefferink should be concentrating on convincing the holdouts to do so, instead of lambasting the nuclear regulator over problems that are not of its making, and not within its powers to resolve.

Nuclear fears

Meanwhile, Begg goes off on a tangent about plans for nuclear energy in South Africa, as if that has anything whatsoever to do with waste from gold mines. Liefferink does try to draw a connection, though: ‘If the NNR does not have the capacity to manage the waste from the gold-mining industry,’ she told Begg, ‘how will it have the capacity to manage waste from more nuclear power plants?’

That is a rather manipulative view. There are clearly different issues at play when informal settlements are established on abandoned mining sites, and when nuclear waste is stored, disposed of, or reprocessed. For a start, there is no prospect of nuclear waste sites ever being abandoned in the way gold mines were.

If the NNR does have the capacity to manage the waste produced by Koeberg, then why wouldn’t it have the capacity to manage waste from more nuclear power plants? By volume, the waste from nuclear power stations is orders of magnitude less than the waste produced by gold mines, or indeed the coal industry.

The whole story is simplistic fear-mongering, filled with exaggerations about the supposed dangers of nuclear radiation. Ultimately, it proposes no solutions to the problem of exposure to abandoned mining waste, but takes gratuitous aim at the entirely unrelated nuclear energy industry.

That is environmental propaganda, not journalism.

Perhaps this should be a lesson to journalists: don’t believe everything environmental activists tell you. They have their own agendas and are willing to lie for them, too.

The views of the writer are not necessarily those of the IRR or Daily Friend.