The local government election at the beginning of this week could possibly be called what Americans describe as a ‘realigning’ election.

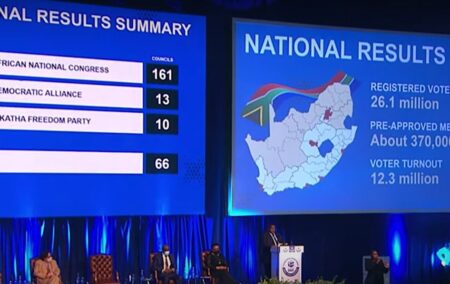

It is the first time in South Africa’s history that the ANC has dipped under 50% in a nationwide poll, a moment of significance that cannot be understated. For the first time, a majority of voters chose parties other than the ANC.

But what can we learn from the election – what are the key takeaways?

The EFF isn’t the natural home of disaffected ANC voters

The EFF, the ANC’s radical offshoot, would seem to be the party for most former ANC voters. Adding the ANC’s and the EFF’s electoral totals for 2019 leaves one with pretty much what the ANC achieved alone in 2009. In 2009, the ruling party won 66% of the vote; in 2019 the combined total for the ANC and the EFF was about 68%.

However, this election has shown that the EFF may have exhausted its supply of former ANC voters, with disenchanted ruling party supporters now going to other parties.

This week, the ANC’s national total dropped by nearly eight percentage points compared to 2016. However, the EFF grew by only two percentage points. This is even more stark when we look at some of the metros, particularly Gauteng.

In Johannesburg, the ANC’s vote share declined by 11 percentage points, while the EFF also saw its vote share decline – by about half a percentage point. Tshwane reflected a similar tale, with the ANC losing about seven percentage points, and the EFF declining too, this time by about one percentage point.

The question is, which parties are disaffected ANC voters turning to?

The rise of local-interest parties

Small local-interest parties have for some time been a feature in the Western Cape, and to a lesser degree in the Northern Cape. However, in this election we saw the emergence of these smaller parties across the country, on a scale sufficient to bring the ANC below 50% in a number of municipalities.

In Lekwa (Standerton), the Lekwa Community Forum won nearly 20% of the vote, with the ANC being brought down to 42%, having won nearly two thirds in 2016. Elsewhere in Mpumalanga, the Middelburg and Hendrina Residents’ Front (MHRF) gained 11% of the vote in Steve Tshwete, with the ANC on 37%, down from 56% in 2016.

In the Free State, the Setsoto Service Delivery Forum won 23% in that municipality (which includes Ficksburg), bringing the ANC down from 61% to 51%. Another Free State municipality, Maluti a Phofung (Harrismith), saw a group called MAP 16 win nearly 30% of the vote, helping to take the ANC down from 67% to 39%.

However, in previous elections we have seen local-interest groups perform well in certain municipalities but then fall away badly later. The Bushbuckridge Residents Association emerged as a real challenger in that municipality in Mpumalanga, even doing well enough to win a seat in the province’s legislature, before collapsing – and it now no longer even participates in elections.

Furthermore, many of these local groupings are often formed by disaffected ANC councillors or activists (as was the case with the Forum for Service Delivery in North West in 2016, the MHRF, and MAP 16) and can sometimes be external wings of the party in certain places.

The next five years will be crucial for many of these local-interest parties in showing whether they can be sustainable opposition groupings or simply turn out to have been a flash in the pan.

The ANC continues to reign in rural South Africa

Despite the setback the ANC suffered this week, it still reigns supreme in rural South Africa. Outside of the Western Cape, KwaZulu-Natal, the Eastern Cape, and Gauteng, it is still the biggest party in every municipality in the other five provinces. In the Eastern Cape there are only two municipalities (Kouga and Nelson Mandela Bay) where it is not the single biggest party, and in Gauteng it is only Midvaal where it is not the biggest.

Although the party slipped below 50% in a number of municipalities in the rural parts of South Africa, in some regions its support remains remarkedly stable, particularly in northern Limpopo and the eastern districts of the Eastern Cape. In Elundini (Maclear) in the Eastern Cape, for example, the ANC won 80% of the vote on Monday, and 82% in Engcobo, in the same province. In Limpopo, the ruling party won just shy of 80% in Makhado (Louis Trichardt) and 85% next door, in Thulamela.

The ANC will likely continue to see its support coming increasingly from the country’s rural areas, shifting away from the metros and the other urban centres.

More coloured-interest parties?

One of the surprises of the election was the performance of the Patriotic Alliance (PA), led Gayton McKenzie, a former gangster.

The party won 74 seats across the country and one percent of the national vote, and could find itself part of governing coalitions across the country. The performance of the PA could be the latest manifestation of the slow rise of a coloured identity politics. As McKenzie was quoted as saying in the Daily Maverick, ‘…the ANC doesn’t care about coloured people. (For the ANC), coloured people are no longer black’.

But the PA is by no means the first of this type of party – election observers have for some time noted the rise of local-interest parties which appeal to coloured South Africans, from the Independent Civic Organisation of South Africa in the Karoo to other movements such as Khoisan Revolution and the Karoo Democratic Force in the Northern Cape.

At the same time, the Cape Coloured Congress did well enough to win seven seats in Cape Town. The party opposes employment equity in any form and is reportedly in favour of a referendum on Cape independence.

As the country continues to degrade economically and resources becoming scarcer it is likely that this type of politics will become more common, especially if coloured South Africans believe they are being excluded from opportunities on the basis of their race.

The fracturing of our politics

Although South Africans voted for the opposition in greater proportions than ever before, they also voted for an even larger number of smaller parties. In 2014 only 9.2% of voters cast their ballot for a party that was not the ANC, the DA, or the EFF. In 2019 this number grew to 10.9%. In the previous local government election the proportion of people who didn’t vote for one of the Big Three was 11%. In this election the proportion of non-Big Three voters was 21.7%. Voters are increasingly looking for new parties and this will likely continue.

To illustrate the fracturing of our politics, the number of parties that won representation on eThekwini’s 222-seat council was 24. Five parties secured two seats each while a whopping 14 won at least one seat.

Although eThekwini was an outlier, many councils across the country will be full of one- or two-seat parties, which could play outsize roles in coalition governments. This will also become more common as more South African voters turn away from the three major parties.

South Africa is now an increasingly competitive electoral democracy and it is only a matter of time before the ANC loses its national majority and its majority in many of the eight provinces it governs.

However, what should concern all of us is the low levels of voter participation in this week’s election. Only about 30% or so of eligible voters (South African citizens over the age of 18) chose to take the time to go to the ballot box on Monday. If voter participation continues to decline, this could start seeing duly elected governments losing the shine of legitimacy in the eyes of those who choose to sit out the electoral process. Arresting and reversing this trend will be a key challenge for South Africa’s democracy in the next decade.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend