That the unemployment rate on the expanded definition now sits above 46% should not come as a surprise. Years of onerous regulations and anti-growth policies (with expropriation without compensation at the top of the list) have contributed to South Africa’s malaise; one in which the size of government continues to grow at the expense of private enterprise. At present, South Africa spends R303 billion annually to service its debt. Edgar Sishi at National Treasury recently indicated that for every R5 that is raised by government, R1 is spent on servicing the debt.

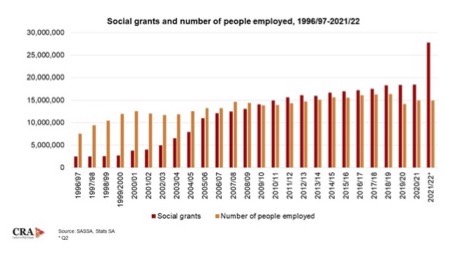

That a record number of people are unemployed, and that ever more citizens are forced into dependence on state welfare, are simply the necessary consequences of the policies that South Africa has pursued over the last 15 years. Implementing a Basic Income Grant, as another example of state control and interventionism, will not lead to the capital formation and job creation necessary to help the jobless millions.

In 2000, South Africa ranked 58th on the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World annual report; in the 2021 edition – based on 2019 data – the country came in at 84th, out of 165 countries and territories. A country’s economic prosperity or decline flows from the ideas and policies that government implements, and those policies flow from the general ideological leaning of the members of said government. Thus when the South African government approaches governance and the economy from the point of view that it is best placed to manage various aspects and ‘guide’ society in the ‘right’ direction, we should not be surprised when destructive consequences follow.

The Employment Equity Amendment Bill was recently adopted by the National Assembly and is currently with the National Council of Provinces. The Bill will allow the labour minister to set employment equity targets for different business sectors. Far from examining whether current labour regulations discourage and restrict business-formation and -expansion, it is clear that government will persist with race-focused policies that serve only to entrench cronyism in the public and private sectors, shrink an already smaller economic pie, and discourage investors and entrepreneurs (of all races) from attempting to start a new business venture.

In their book, The Myth of the Entrepreneurial State, Alberto Mingardi and Deirdre McCloskey write:

“The enriched modern economy was not, however, a product of State coercion, whether difficult or easy. It was a product of the happy chances of a change in political and social rhetoric in northwestern Europe from 1517 to 1789. People – regular people, the hobbits of the Shire and not the almighty warriors from afar – began to perceive themselves in a new and dignified light (Aufklarung), and, crucially, came to feel their artisanal and commercial undertakings to be more appreciated socially. They were permitted to ‘have a go’, as the British say, and proceeded then to innovate on a massive scale.”

Can we say that, in South Africa, the general treatment of business and entrepreneurship takes place from a perspective of support, or rather one of antagonism, irritation, and ever more attempts at ‘shaping’ and ‘managing’ the market? Judging by the spate of state-focused policies over the last 15 years, the answer should be an unequivocal no.

In the 2021 Medium Term Budget Policy Statement, the Treasury forecast South Africa’s gross debt-to-GDP ratio at 69.9% for 2021/22; given that there haven’t been substantive cuts to spending, this will likely trend upward over the next few years. The greater government spending grows, the more revenue it requires to maintain its functions; accordingly, it then consumes more of the economic activity that is generated in the market. This serves to discourage market forces and business activity; more often than not spending by the state is greatly inefficient.

The mindset at present is one of redistributionism and control, rather than pursuing the independent wealth creation that would accompany more pro-free market policies.

The over-burdened (as a result of its own policy choices) central government can do inordinate good for small, medium, and large businesses across the country by simply doing less. Exemptions from labour regulations, onerous employment requirements, exemptions from certain taxes, and freezing the National Minimum Wage for a fixed amount of time are all examples of steps the state could take without having to find more money in a perilously listing fiscus for yet more forms of welfare and stimulus.

It is likely that the necessary positive changes will not come about because of a change at the very top of national government, but rather through citizens and small-to-medium enterprises ensuring that their daily work and operations are adequately state-proofed. Ultimately ‘the market’ is simply people interacting with each other in various ways, creating value and solving all manner of challenges. One of the best ways to fight back against ever-encroaching government is to render the plans of bureaucrats and politicians moot, by putting the necessary structures in place so that their machinations do not cripple your quality of life.