European supermarkets recently put the kibosh on Brazilian beef, because some of it may be tainted by deforestation. This is a poorly-directed gesture that will cause more harm than good.

A new report by Repórter Brasil, entitled Cattle eating up the world’s largest rainforest, alleges ‘cattle laundering’ on the part of Brazil’s largest meat processing company, JBS S.A., which is also the world’s biggest butcher.

Although the company has official policies not to procure beef or other livestock products from land that has been illegally deforested, the vast network of suppliers to its direct suppliers are able to conceal the use of non-approved, deforested land by selling cattle along a convoluted and opaque supply chain.

The company was at pains to point out that it has blocked more than 14 000 suppliers for non-compliance, and that the report implicated only five of its 77 000 suppliers. Upon investigation, all five were in compliance with the company’s policies at the time of purchase. It says due to confidentiality clauses, it is hard to gain transparency into the suppliers of its suppliers.

JBS operates a sophisticated satellite geospatial monitoring system to keep tabs on its suppliers, and is working to implement a blockchain-based livestock origin tracing system to peer ever-deeper into its supply chain.

It has committed – besides being carbon neutral by 2040 – to eliminate illegal Amazon deforestation from its supply chain, including the suppliers of its suppliers, by 2025, and in other Brazilian biomes by 2030. The company has pledged to achieve zero deforestation across its global supply chain by 2035.

Peculiar approach

Despite all this, a number of major European supermarket chains have agreed to boycott Brazilian beef, and particularly that of JBS.

This seems a peculiar approach to appease Western environmentalists. Consumers in the world’s richest countries, importing products produced on deforested land, account for only 14% of the world’s deforestation.

Believing that a boycott of one, or even several, specific products – such as beef, or palm oil – will make a meaningful impact on deforestation is wishful thinking.

The people harmed by product boycotts may include a few implicated in deforestation, but the vast majority are likely entirely innocent. JBS alone employs a quarter of a million people. Its 77 000 suppliers provide jobs for untold more. All these people will be impacted.

Those who lose their jobs won’t just conveniently disappear. Pushed out of the legitimate, above-board agriculture industry, they will likely join other, less scrupulous companies that are harder to hold to account, or to branch out on their own free from onerous policies that commit them to protecting the local rainforest.

If enough other countries follow suit and make Brazil beef untouchable, local livestock farmers aren’t just going to take nice, eco-friendly jobs as tourist guides. They’re going to do what they know: farm.

They’ll just switch from an anathema product to another, that doesn’t have the same reputation. Has anyone threatened to boycott Brazilian soy yet? Or Brazilian chicken? Or anything else that can be grown or raised on recently deforested farmland?

Scale of deforestation

The Amazon is top of mind when it comes to deforestation. Brazil and Indonesia together account for almost half of global rainforest loss. Yet even there, the scale of deforestation is not as alarming as activists would have you believe.

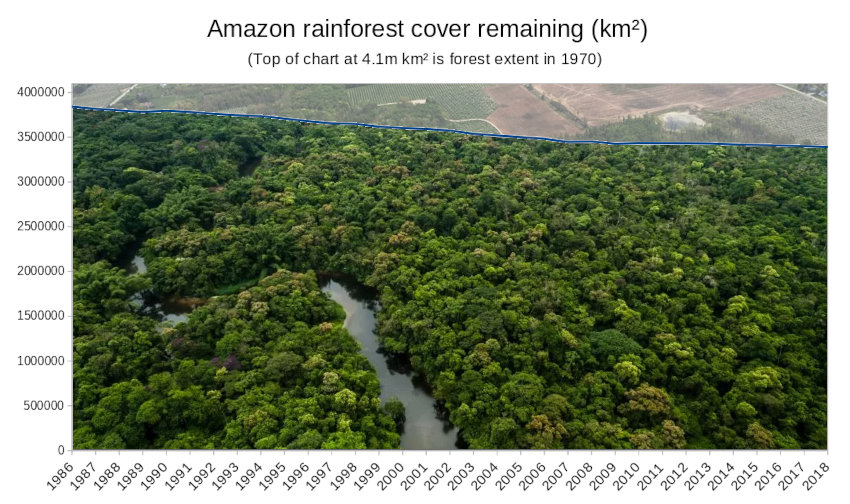

This chart represents the total area of the Brazilian Amazon rainforest that remains, compared to its 1970 extent:

The main deforestation fronts are not only where they are expected, in Brazil, Indonesia and Malaysia, however. They have changed significantly in recent years. On a global scale, Africa has the highest annual rate of net forest loss in 2010-2020 with 39 000 km2 hectares, followed by South America with 26 000 km2.

Asia, on the other hand – which includes Indonesia and Malaysia, where oil palms are often grown – had the largest net gain of forest area in 2010-2020.

By country, Brazil remains at the top of the list of coutnries with the most primary forest loss in 2020, accounting for over 40% of global forest loss. After a significant decline in deforestation up to 2012, the rate of forest loss has increased again in recent years.

This uptick is linked to a policy of aggressive agricultural expansion that resulted in the conversion of primary forests for agriculture, and particularly for extensive livestock cultivation.

Clear-cutting and the use of fire have multiplied to facilitate these agricultural developments. Many fires became uncontrollable due to drought and devastated large portions of the Amazon.

The Democratic Republic of Congo and Bolivia are in second and third place, behind Brazil. There, too, the primary cause of deforestation is cattle ranching, and uncontrolled forest fires that have ravaged thousands of hectares.

Indonesia and Malaysia, which for years have been singled out and associated with the development of industrial oil palm crops at the expense of forests, are now cited as examples of countries that are effectively reducing deforestation. For the fourth year in a row, these two countries have reduced the loss of primary forest.

The World Resources Institute calls them ‘bright spots of hope’, and attributes the improvements in part to corporate commitments in the pulp and paper as well as palm oil industries.

Improving global trend

These countries and industries are leading the way to establish a global trend which is one of improvement.

Asian countries are showing that it is possible to reduce or even reverse forest destruction. There is no one-size-fits-all solution that can work for all countries, however, because the reasons for the loss of forest area are specific to each country. And as Brazil’s beef industry shows, such gains can be reversed.

The world still has at least 11.1 million km2 of primary forest. Combined, three countries – Brazil, Canada and the Russian Federation – host more than half (61%) of the world’s primary forest.

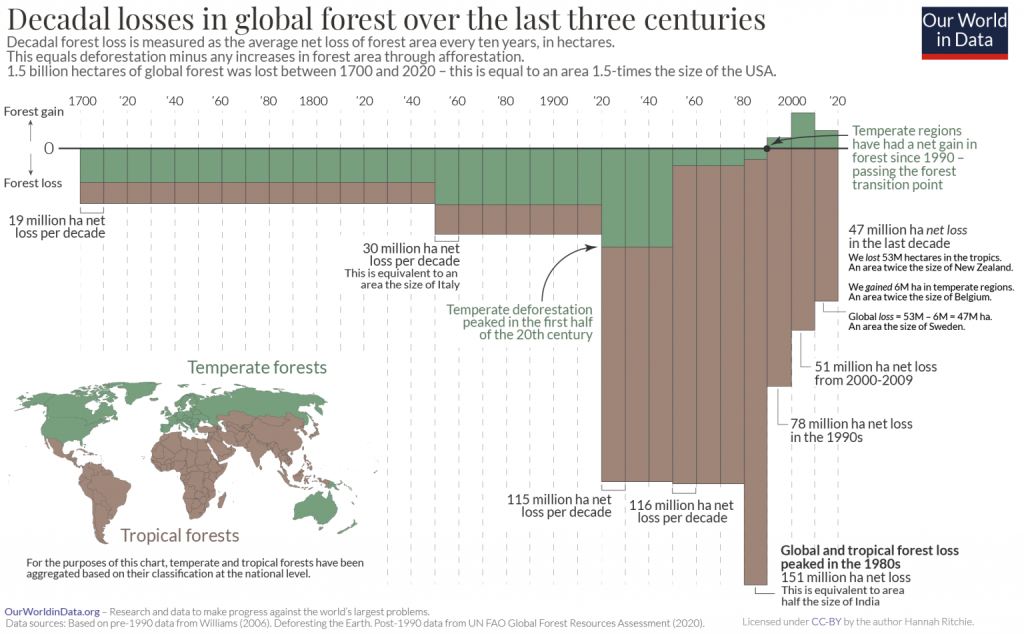

The area of primary forest has decreased by 810 000 km2 since 1990, but the rate of loss more than halved in 2010 to 2020 compared with the previous decade. Forest loss peaked in the 1980s, and has declined to a third of that level since then.

U-shaped curve

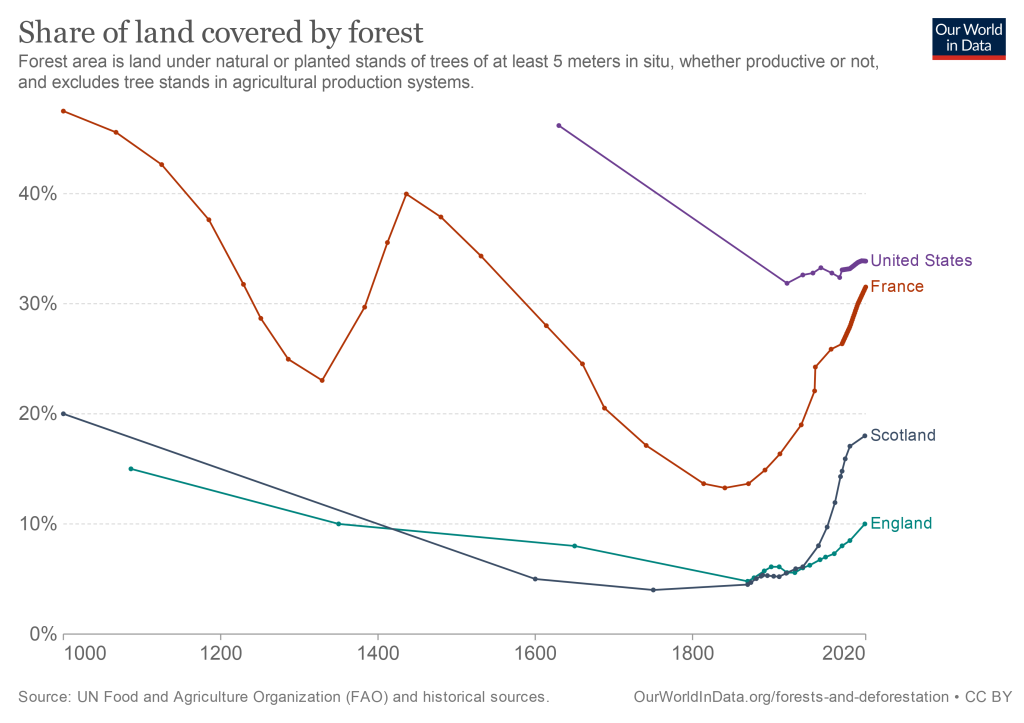

Like with most environmental problems, however, forest loss is a problem of early economic development. Once a country reaches a certain level of prosperity, forest cover begins to recover, leading to a U-shaped curve of forest cover:

Most rich countries have gone through their deforestation stage, and have come out the other side both prosperous and with its forests recovering. It seems wrong to deny developing countries the same latitude, especially since they are hardly razing forests on the scale that Western countries once did.

Telling poor countries to prioritise their environments over human development, when Western countries never did that when they were developing seems awfully hypocritical, and not a little misanthropic.

In fact, Australia is still a deforestation hotspot, according to the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF), especially in Victoria, Queensland, and parts of New South Wales. There, too, loss of forest cover is linked to the beef industry.

Are European supermarkets going to be consistent and ban Australian imports, too?

Cold hostility

In most industries that are accused of deforestation, only a small minority of the industry participants are actually guilty.

Product boycotts do not discriminate, however. They punish entire countries, and entire industries, to satisfy the sensibilities of Western environmental activists.

They are also not particularly effective. High-profile companies like JBS have a brand and reputation to protect. They are likely to be at least somewhat responsive to pressure from international customers. Boycotting them, however, pushes harmful environmental practices underground, where it is far harder, or impossible, to exert pressure.

Western activists who seek to promote change in developing countries would do better to recognise the human development imperative. Reducing deforestation depends on local environmental laws and enforcement capacity. It depends on cooperation with local industry players. It depends on finding alternative ways for local farmers to put bread on the table.

The WWF believes that industries such as palm oil can contribute to sustainability, if conducted with due care: ‘Responsible palm oil should be produced without causing deforestation, the conversion of natural ecosystems, environmental degradation, or the harming of wildlife. It should also be produced in a manner which treats workers fairly, respects the rights of local communities and indigenous people, and incentivises and empowers producers including smallholder farmers with the means to adopt more responsible production practices as a part of sustainable livelihoods.’

These are the concerns that matter. Instead of the cold hostility of boycotts, rich countries ought to support reforestation and capacity building projects that focus on providing local communities with sustainable revenue opportunities that do not rely on forest timber or deforestation.

Such projects, and cooperation with local industries, foster trust and goodwill. By contrast, boycotts and condemnation harden the nationalist impulses that have become a hallmark of populist Brazilian politics in recent years.

Counter-intuitively, boycotts will cause more deforestation, not less.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend