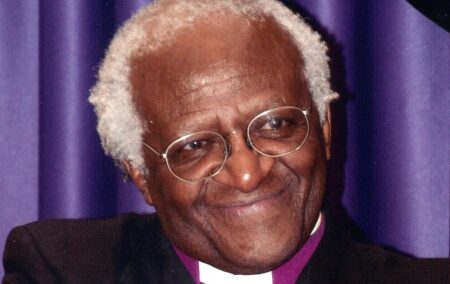

With the death of the venerable Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Mpilo Tutu, South Africa has lost a remarkable soul, overflowing with decency and humanity. He, perhaps in vain, pointed the way to the high ground of non-racialism and reconciliation.

I never met the Arch, but I once walked very close to him.

The occasion was an abortive memorial service for the recently slain leader of the South African Communist Party, Chris Hani. The venue was the streets of Cape Town.

Tensions were running high. Many naysayers of a negotiated settlement had predicted that South Africa would descend into civil war, especially when talks deadlocked time and time again. In April 1993, when two white right-wingers, Clive Derby-Lewis and Janusz Waluś, assassinated Hani, the awful prospect of tensions exploding was palpable in the air.

I, still a student at the time, was working a menial clerical job in the city centre, and we had been given the afternoon off because the streets were filling up with protesters. I made my way on foot to St. George’s Cathedral to attend the service, but was running ten minutes late.

Walking up Adderley Street, I encountered the Arch leading a procession away from the cathedral, back down the road, towards the Grand Parade, where a restive crowd was gathered and violence was a very real prospect.

Armed with shotguns, the riot squad – which in 1993 still had a vicious reputation for shooting first and asking questions later – had taken up positions in the streets leading to the Grand Parade.

As Tutu and his entourage made their way through the crowd to the stage that had been erected at the far end of the Grand Parade, angry protesters began to break plate glass windows, loot shops and set a Post Office van alight.

I could hear the commands given to the police ranks. I got out of the firing line. Being white, albeit long-haired, I was permitted to cross the police line. Not everyone was that lucky before the shotguns began to bark. A guy who got birdshot in the back was bundled to safety. When I went to check if he was okay, he spat in my face.

I wasn’t angry. He was, and he had reason to be. He saw a white face and white faces were the cause and object of his anger. It was hard to hold that against him, under the circumstances.

Oil on troubled waters

Then, from diagonally across the Parade from me, Tutu began to speak. For a tiny man with a squeaky voice and a high-pitched giggle, he projected a giant aura. His exact words I cannot remember, but they came from a place of great love and forbearance.

He acknowledged the justifiability of the crowd’s anger. He led them in renewing their demands for democracy, freedom and an end to violent oppression. Despite validating the emotions of outrage that roiled through the crowd, his words flowed like oil on troubled waters. Despite the provocation of white policemen shooting at protesters on the other side of the Grand Parade, the violence subsided under the spell of Tutu’s voice. Peace was restored.

That was the day I realised what a powerful magic Desmond Tutu really commanded. It was hard to believe that his sheer humanity, his relentless belief in peace, and his determination to include both black and white as equals in the rainbow nation of his visions, could quiet a violently angry crowd, yet there we were.

Religious man

Looking back now, I find myself surprised at the deep respect I continue to have for such a deeply religious man. Ordinarily, religious people evoke in me a sense of distrust, with their dogmatism, conservatism, authoritarianism, bigotry and hypocrisy.

As a secular humanist, I reject not only their anti-rational belief in the supernatural, but also their claim that morality requires adherence to a selective interpretation of the prescripts of ancient writings.

However, Tutu’s religious convictions, while never hidden – one of his reasons for opposing Marxism-Leninism was its atheism – were never a burden on anyone else. He did not proselytise. He did not exclude or judge those who did not believe as he did.

When he was called upon to preside over the religious aspect of Nelson Mandela’s inauguration in 1994, he made a point of including Muslim, Jewish and Hindu leaders. He never rejected those whom his church’s doctrine would have condemned as heathens.

Tutu prayed not only for the victims of apartheid, but also for its perpetrators and for the white voters who supported them.

‘Sometimes I get angry,’ Tutu told the Washington Post’s Pete Early in 1986, just over a year after receiving the Nobel Peace Prize. ‘Sometimes that feeling of anger is so intense that I have to ask myself if it isn’t, you know, bordering on hatred.’

He told Early: ‘I pray for the government by name every day. You see, if you take theology seriously, whether you like it or not, we are all members of a family – God’s family. They are my brothers and my sisters too. I might not feel well disposed toward them, but I have to pray that God’s spirit will move them.’

In a world of preachers who condemn their political enemies as agents of evil, this was refreshingly forgiving and non-judgmental. And the thing is, he didn’t have to be. If he was condemnatory, and called down God’s wrath upon the apartheid regime, nobody, but nobody, would have blamed him. Everyone would have agreed.

Gay rights

He openly criticised his own Anglican Church over its views on gay priests, calling it ‘extremely homophobic’.

He said: ‘Our world is facing problems – poverty, HIV and Aids – a devastating pandemic, and conflict. God must be weeping looking at some of the atrocities that we commit against one another. In the face of all of that, our Church, especially the Anglican Church, at this time is almost obsessed with questions of human sexuality.’

Of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, he said: ‘Why doesn’t he demonstrate a particular attribute of God’s which is that God is a welcoming God?’

On the occasion of the launch of the United Nation’s gay rights campaign in 2013, he was even more blunt: ‘I would not worship a God who is homophobic and that is how deeply I feel about this. I would refuse to go to a homophobic heaven. No, I would say sorry, I mean I would much rather go to the other place. I am as passionate about this campaign as I ever was about apartheid.’

Tutu was a rarity among religious leaders: he was open-minded and he was a humanist first.

Self-described socialist

I also find myself surprised at the deep respect I continue to have for a self-described socialist.

When I was young, and just escaped from the racist indoctrination of Christelik-Nasionale Onderwys, I made the same mistake as the Arch, believing that free enterprise had been given a bad name by the apartheid regime, and preferring a more humane socialism.

After all, the socialist left were the ones on the right side of the defining moral struggle of my youth, the liberation from apartheid in particular, and racism in general.

‘All my experiences with capitalism, I’m afraid, have indicated that it encourages some of the worst features in people,’ he told Early. ‘Eat or be eaten. It is underlined by the survival of the fittest. I can’t buy that. I mean, maybe it’s the awful face of capitalism, but I haven’t seen the other face.’

He condemned communism, but also said that communists weren’t oppressing black South Africans. That was hard to argue with.

I still think it is one of the great tragedies of the 20th century that the Cold War poisoned the decolonisation movement. Soviet support for liberation struggles around the world, though largely motivated by its own geostrategic considerations vis-à-vis the West, gave socialism a veneer of moral authority and respectability that it never deserved.

Conversely, Western tolerance for odious regimes, merely on the grounds that they held the line against Soviet expansionism, made capitalist countries complicit in oppression, discrimination and human rights violations, even though these things violated the principles on which the West’s liberal democracies were based.

To this day, the legacy of socialism is a cancer in formerly colonised countries, perpetuating poverty, autocracy and human misery. To this day, the morally superior principles of classical liberalism are given short shrift by those who remember who their friends were during the Cold War.

Truth and reconciliation

Perhaps Tutu’s greatest claim to fame was chairing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). Its mandate was to give voice to the many victims of political crimes, at the hands of both the apartheid regime and the liberation struggle against it. It also provided a venue where perpetrators of political violence could come clean, confess to their victims and the nation, and, if they were truthful, receive amnesty for their crimes.

In the end, 849 people were granted amnesty, and 5 392 petitions were refused.

As a means of dealing with human rights violations in the wake of a political transition, it was widely hailed as a successful alternative to the retributive justice exemplified by the military tribunals of Nuremberg. It was, though with limited success, adopted elsewhere as a model for achieving peace, restorative justice and reconciliation.

However, it had flaws. To many people, amnesty did not look like justice. Worse, key people, such as 1980s state president P.W. Botha, simply refused to appear. Many of those who were refused amnesty, such as the six policemen held responsible for the murders of the Cradock Four, were never brought to justice.

Although it was a testament to Tutu’s commitment to reconciliation, dignity, and human rights, it also in a way exposed the almost child-like naïveté of Tutu’s approach to justice.

That naïveté extends also to his vision of the ‘rainbow nation’, in which black and white would live together in perfect harmony (to quote Paul McCartney and Stevie Wonder).

Tutu himself would turn around, in 2013, to say that he could no longer vote for the ANC, because it had become a ‘betrayal of our whole tradition’, had become mired in corruption, and was unable to resolve the problems of inequality and poverty in South Africa.

Moral high ground

I agreed with Tutu on some issues, and differed with him on a number of others. On some, like the Iraq War, I first differed with him and then came to agree. Yet even for my most fundamental differences with him, on religion and socialism, the Arch could not do other than command my utmost respect.

His dream of a rainbow nation now seems hopelessly idealistic, but in its non-racial intent it remains a goal worth striving for. In many ways, Tutu’s humanity reflected the best of South Africa, during the liberation struggle, the transition years, and beyond.

His uncompromising commitment to peace, justice, humanity, dignity and reconciliation should forever remain a guiding star in South African politics.

Those who seek to divide us, should be admonished as Tutu would have admonished them, with honest recognition of their grievances, but with the exhortation to hold the moral high ground, even against enemies.

The Arch exemplifies an era in South African politics, perhaps just as much as Nelson Mandela himself did. It would be sad to think that his vision of what South Africa could be might die with him.

Let’s not let that happen.

[Image: University of Mount Union, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=89464930]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend