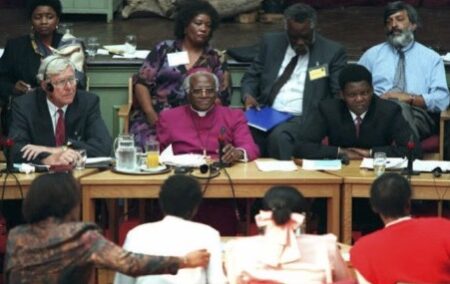

Chaired by Desmond Tutu, South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission was hailed both in this country and around the world. But its methodology was flawed, its concept of “truth” spurious, its omissions significant, and its conclusions one-sided. It overturned or ignored judicial decisions without explaining why, paid insufficient attention to some of the important evidence put before it, and often failed to give reasons for its findings.

Established in 1995, the commission was mandated to provide a factual, comprehensive, properly contextualised, and even-handed account of killings and other gross human rights violations committed on all sides between March 1960 and May 1994.

During this period, the worst political violence occurred between 1984 and 1994, when 20 500 people were killed. But the commission probed fewer than half of these. In particular, it failed properly to explore the reasons for the major upsurge in political violence in the 1990s after the bans on various organisations had been lifted. Accordingly, at least 12 000 killings were left unexplained.

In its report in 1998, the commission assigned accountability for certain violations to the African National Congress (ANC), the United Democratic Front (UDF), and the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC). But it blamed most of the violence on the former National Party (NP) government and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP). It did this while paying insufficient attention to evidence they presented.

Although it paid lip service to the notion of factual and objective truth, the commission invented “narrative”, “dialogue”, “healing”, and “restorative” truth. It received 21 300 victim statements, many of them hearsay, and few of them given under oath or tested under cross-examination. Statements of this kind were nevertheless used as the basis for findings of premeditated murder against named individuals and organisations, the commission having expressed reservations about applying the principle of audi alteram partem.

Several massacres were ignored by the commission, without explanation. Sometimes the fatality figures it gave contradicted those of other inquiries, also without explanation. Sometimes previous judicial decisions were simply reversed, yet again without explanation.

The commission thus named a certain police sergeant as one of those accountable for the Trust Feed massacre in the Kwazulu-Natal Midlands in 1988, in which 11 members of the IFP had been killed. The sergeant had earlier been acquitted in a criminal trial. But the commission gave no evidence for this new finding, nor did it provide any reason for its reversal of the court’s verdict.

The commission made another strange decision over Trust Feed. A police captain, Brian Mitchell, had been given 11 death sentences (later commuted to 30 years’ imprisonment) in 1992 for his part in the massacre. In 1996 the commission granted him amnesty on the grounds that he had made the required “full disclosure” and that his offences were “part of the counter-revolutionary onslaught against ANC and UDF activists” (although IFP members had been killed by mistake). He was given amnesty despite having repeatedly told the commission’s amnesty panel that he had not been present when the massacre took place. One of the members of the panel was his trial judge, who had found that Captain Mitchell had not only been present but that he had also “given the signal for the attack to start” by firing two shots at the house. The commission did not explain why it now accepted that Captain Mitchell had not been present when the trial court found that he had.

Sometimes the commission cited alternative findings which it then overturned, also without explanation. One example of this is the commission’s findings on the Boipatong massacre near Sharpeville in June 1992. Comparing it to Nazi murders of Jews, Nelson Mandela blamed it on the government and the IFP. Cyril Ramaphosa blamed it on FW de Klerk. The ANC claimed that the police had ferried the attackers into the township from the nearby KwaMadala hostel. This allegation went around the world.

British police investigators brought in by the Goldstone Commission found no evidence of the police involvement that the ANC alleged. A trial judge subsequently convicted 17 IFP members from the hostel of the killings of 45 Boipatong residents. Evidence of police involvement crumbled under cross-examination, and was dismissed by the judge.

The commission quoted these findings. It then proceeded to find that the police had not only been involved in the massacre, but had planned it. It cited no fresh evidence to substantiate this contrary conclusion – a contrary conclusion reached despite a far more rigorous examination of the evidence than the commission itself conducted. Some years later an amnesty committee set up by the Truth Commission itself found no evidence of police involvement.

The commission’s pronouncements on the Shell House shootings in March 1994 are another example of how it ignored other findings. It stated that the killing of eight IFP supporters outside the ANC’s headquarters had taken place in response to an IFP assault on that building. Yet an inquest headed by Judge Nugent had earlier found that no such assault had taken place. Far from explaining why it differed from the Nugent findings, the commission ignored them.

After a trial in 1996, Magnus Malan, a former defence minister, was acquitted of conspiring to murder ANC and UDF members by training IFP “hit squads” in the Caprivi strip. The Goldstone commission had earlier found no evidence that the training of IFP members had been for “hit squad” purposes rather than self-defence. The Truth Commission found the opposite, but did not disclose why it had rejected the trial court’s findings, which had themselves been explained in great detail by the judge.

The commission castigated the NP government for the methods of “counter-revolution” that it employed. But despite its mandate for a comprehensive and contextualised account, it failed adequately to probe the revolutionary activities against which the NP’s security forces had waged their counter-revolution, which included the murder of political activists.

Numerous submissions to the commission gave plenty of detail about the role of revolutionary violence in the “armed struggle” waged by the ANC and its allies, especially after it had evolved into the “people’s war” in the 1980s. A submission by the police claimed that the people’s war had led to 9 200 deaths over an eight-year period. The commission’s report acknowledged the people’s war, but failed to probe it in sufficient depth.

One of numerous examples of differential treatment is that the role of the State Security Council was extensively investigated, but no equivalent attention was paid to the role of the ANC’s Politico-Military Council. Arms illegally acquired by the IFP were given more attention than those brought into the country by the ANC, even after 1990. So also, the role of the IFP’s alleged hit squads was probed far more extensively than that of Umkhonto we Sizwe.

The commission found that the NP government was running a criminal state, and found also that the IFP – acting as that government’s surrogate – was responsible for repeated attacks on the ANC. But it failed properly to investigate the IFP’s allegation and evidence that the ANC was waging war against its political rivals, notably the IFP.

In normal criminal trials, evidence is subjected to cross-examination in order to ascertain all the relevant facts, while judges are obliged to give reasons for their decisions. The commission set for itself much lower standards in trying to establish the truth, which it defined in ways falling far short of what courts would regard as truth. On the basis of this fundamentally flawed procedure it proceeded to level accusations of the utmost seriousness. Although it was an inquiry rather than a court, the commission was not entitled to do this, still less to overturn judicial decisions reached after far more rigorous procedures.

The commission failed in particular fully to probe the period of the most intense political violence, let alone explore the impact of the ANC’s openly declared people’s war. By effectively ignoring the majority of deaths in political violence the commission betrayed not only those thousands of victims but also its own mandate to provide a factual, comprehensive, and even-handed account of the violence which preceded the 1994 election.

As a result we have only a partial, selective, and distorted version of the “truth”.

* This article is based mainly on The Truth about the Truth Commission by Anthea Jeffery, published by the IRR in 1999.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend