Six weeks ago, as Russia prepared to invade Ukraine, this column described how Stalin killed 3.9 million Ukrainians by starvation in the early 1930s. He inflicted famine upon that country in order to collectivise agriculture, but also to destroy Ukrainian national consciousness.

All this was chronicled first by Robert Conquest in The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivisation and the Terror Famine, published in 1986. Many years later, in 2017, Anne Applebaum published another account of what happened in Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine.

Ms Applebaum’s book included a chapter entitled ‘The Cover-Up’. This recorded how The New York Times (NYT) had downplayed the famine: ‘There is no actual starvation but there is widespread mortality due to malnutrition’. Walter Duranty, the paper’s Moscow correspondent from 1922 to 1936, won a Pulitzer Prize for his reporting.

Not many more years later, that same newspaper chose to downplay Adolf Hitler’s policy of exterminating Jews. This was the subject of a book by Laurel Leff entitled Buried by the Times – The Holocaust and America’s Most Important Newspaper, published in 2005 and discussed in this column on 29th March last year.

Ms Applebaum wrote that ‘many European foreign ministries had superb information about the famine as it was happening’. Italian, German, Polish, British, and Canadian diplomats not only had the information about its effects, but also understood that it was being inflicted as a matter of policy. The Italian consul in Kharkiv said it was ‘organised to teach a lesson to the peasants’ while also leading to the ‘colonisation of Ukraine by Russians’. Polish diplomats said that the famine and persecutions were part of the ‘long-term policy of the Moscow leaders, who are more and more becoming imperialists’.

According to Ms Applebaum, foreign journalists posted to Moscow were also aware of what was happening. But they were subject to controls, risking expulsion if they offended the Soviet authorities, so they did not want to run risks by reporting on the famine. Mr Duranty was among those who knew about it, she says. He had indeed told a British diplomat in Moscow that as many as 10 million people might have died from lack of food. Later he wrote that the lot of kulaks and others who opposed the Soviet experiment was not a happy one, but that the suffering had been inflicted with a ‘noble purpose’.

One great exception

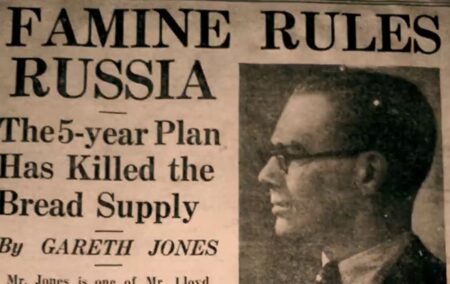

There was one great exception, Gareth Jones, a young Welshman who managed to get permission to visit Ukraine. He walked through more than 20 villages and collective farms, seeing rural Ukraine at the height of the famine. He shared food from his backpack with starving people, sleeping on the floors of peasant huts, listening to their stories, watching how they desperately scratched for food, recording everything in notebooks.

He then slipped out of the country. On 30th March 1933, he told a press conference in Berlin that a major famine was unfolding in the Soviet Union: ‘Everywhere was the cry, ‘There is no bread. We are dying.’’ His remarks were reported in a couple of American newspapers and he published articles in a dozen other papers in London, Cardiff, and elsewhere.

The Soviet authorities were furious. But, according to Ms Applebaum, ‘the Moscow press corps was even angrier’. Of course, she adds, they all knew that what he had reported was true. Years later, Eugene Lyons, Moscow correspondent for United Press, wrote that all foreigners in the city were aware of what was happening in Ukraine. Nobody had any doubts about it. ‘The famine was accepted as a matter of course in our casual conversation at the hotels and in our homes’. He also wrote that ‘the facts [Mr Jones] had so painstakingly garnered from our mouths were snowed under by our denials’.

‘Throwing down Jones was as unpleasant a chore as fell to any of us in years of juggling facts to please dictatorial regimes – but throw him down we did, unanimously and in almost identical formulations of equivocation’.

The day after Mr Jones’s press conference in Berlin the NYT ran a headline ‘Russians hungry but not starving’ over an article by Mr Duranty. It dismissed the Jones reports as a ‘big scare story’, adding that his own ‘exhaustive inquiries’ had shown that ‘conditions are bad, but there is no famine’. Mr Duranty also stated, ‘To put it brutally, you can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs.’

‘Masters of euphemism’

Gareth Jones replied by way of a letter to the editor of the paper, citing a huge range of interviewees, among them more than 20 consuls and diplomats, to corroborate his observations. He also denounced how Soviet censorship had turned the Moscow press corps into ‘masters of euphemism and understatement’. But he could not compete with the famous Walter Duranty, whom nobody else was willing to challenge. So, writes Ms Applebaum, ‘there the matter rested’. Mr Jones was murdered by Chinese bandits a few years later while reporting in Manchukuo, a puppet state set up by the Japanese after they invaded Chinese Manchuria in 1931. His story is the subject of a film, Mr Jones, released in 2020.

According to Ms Applebaum, ‘Russians hungry but not starving’ became the accepted wisdom. Moreover, as one British official commented, ‘we have a certain amount of information about famine, but we do not want to make it public because the Soviet government would resent it’. This, of course, was at a time when there was increasing fear in Europe about the rise of Nazi Germany, accompanied by the idea that an alliance with the Soviets was necessary to counter Hitler.

[Image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/diego_sideburns/49114676033]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend