In a recent article, commentator Stephen Grootes writes: “It is important to determine which economic factors are in the control of the government, and which are not. Additionally, it is rather instructive to understand which calamities were forced upon us by the ANC itself.”

Grootes touches on increasing fuel and food prices, and rising inflation, as some of the biggest pressure points on South African society.

His analysis would be enriched by applying the lens of ideology to the ruling party’s policy choices of the last ten years. The National Democratic Revolution – and the prescript that the ruling party must control the levers of state, society and the economy – ensure that the ANC is largely coterminous with the state. This is the driving force behind the country’s economic destruction.

South Africa’s economic freedom has been steadily eroded by policies such as BEE, an environment hostile to small and medium enterprises, a government-enforced monopoly in electricity generation and distribution in the form of Eskom, high taxes, as well as inflation and the resulting devaluation of the currency. Wealth redistribution, as opposed to wealth creation, has been the chosen path. The result is that around 46% of the population receives some form of grant.

In policy terms, expropriation without compensation, in the form of the Expropriation Bill and the Land Court Bill, is clearly still on the table. Such measures will undermine the property rights of all South Africans. They will also erode the very concept of secure property, a critical ingredient for any economy aspiring to grow. The National Health Insurance – effectively putting the management of all healthcare financing in the hands of the state – will not solve any of the problems in private or public healthcare, and will drive health professionals away. Prescribed assets and the seizure of pension funds remain alluring to bureaucrats who need money to bankroll a consistently growing, but fundamentally under-delivering, public sector workforce.

The Employment Equity Amendment Bill will, if adopted, allow the labour minister to set binding race-based ‘numerical targets’. The minister will be empowered to set different quotas for different sectors, and to do the same for different regions. Businesses that fail to meet these race reservation targets repeatedly can face punitive sanctions of up to 10% of their annual turnover.

Given the massive damage caused by cadre deployment and patronage networks over the last decade, as exemplified by state capture, there is every reason to predict that increased ‘equity’-based legislation will only further incentivise corruption, heighten business costs, and dissuade people from undertaking the risks associated with starting and growing new enterprises.

Political connections

Most unfortunate of all, as has been the case with BEE legislation, those citizens who are intended to benefit from such policy will be left behind. Instead, it is those with the necessary political connections who will benefit. This is in effect a badly distorted form of redistribution, from the country’s taxpayers (through the cost to the fiscus of these measures) and the poor (in terms of forgone opportunities) to a politically fixed class of cadres.

The commodities boom of the last year has helped to bolster the fiscus and afforded the country a measure of breathing room. With conflict in Ukraine, there is a new possibility that South Africa could benefit from increased exports – another commodities boom.

However, the potential wins are undermined, if not cancelled, by Localisation Master Plans, which are in various stages of implementation. Localisation can be realised through two broad avenues, which may be applied concurrently: either subsidies and other forms of state support for local companies; or higher tariffs and import duties on imported materials, inputs, and goods.

It is unclear how the companies and products deemed worthy to receive state support are decided upon. This opens up more avenues for economic inefficiencies and cronyism. And purposefully increasing the cost of imported goods – which struggling South African consumers buy voluntarily – is pure economic madness.

Localisation will furthermore not solve any of the structural problems that afflict the country’s ports and rail infrastructure. If truly opened up to private sector investment and skills development, these would unlock meaningful and sustainable industrialisation – and increase the country’s standing in implementing the Africa Continental Free Trade Area, which ought to be all about lowering barriers to trade.

That South Africa currently has an unemployment rate above 46%, and an average growth rate forecast at just 1.8% over the next three years, should not come as a shock. Economic decline, fewer job opportunities, and the concentration of an ever smaller, fixed amount of wealth in the hands of those with the necessary political clout are the inevitable consequences of the ruling party’s ideological and policy choices.

The economy’s 4.9% rebound in 2021 has by no means undone the damage wrought by Covid-19 and lockdowns. The economy contracted by 6.4% in 2020, one of the worst-affected in the world.

Extensive state intervention

South Africa will fall further behind, especially as measured against its emerging market peers, in terms of growth and quality-of-life improvements for as long as policies based on extensive state intervention and control are implemented. The attempt to redistribute money to create prosperity has proved futile and self-defeating, especially because ours is not an environment that fosters serious capital formation and investment.

While it is true that global events can shape a country’s economic fortunes, governments are also fully capable of shooting themselves – and most importantly, the people – in the foot, making them all the more vulnerable to unexpected shocks.

Covid-19, lockdowns, and now the Russian invasion of Ukraine all serve to expose the massive damage done to the country and the economy by the ruling party. Shifting to a better ideological framework – a market economy, limited government, non-racialism, the rule of law, individual dignity and agency – will change the aim and content of the policies formulated by politicians and bureaucrats, and put the country on a better footing for the future.

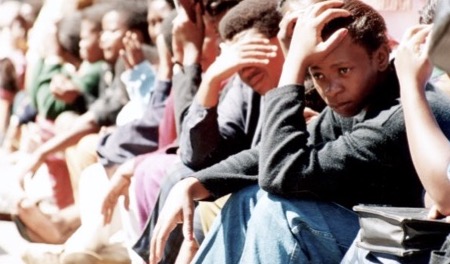

[Photo: IOL]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend