When somebody talks about Paris, what immediately comes to mind is the Eiffel Tower and starry-eyed couples walking along the Seine. Less likely to come to mind are the impoverished estates on the outskirts of the City of Light, where many people who feel left behind by the French state live.

Cape Town is similar. When many people – South Africans and foreigners – think of Cape Town, what comes to mind are the beaches, Table Mountain, and rolling vineyards, rather than the gang violence and shanty towns that are a feature of many South African towns and cities.

Of course, many of the world’s great cities have a dark underbelly – Cape Town and Paris are certainly not unique.

Changing perceptions

But very rarely does a city manage to change the outside world’s perception of itself, especially if this perception is negative. It takes a colossal effort by politicians, residents, and businesses to do so.

And for perceptions to be changed, the city itself must be changed – if a city is viewed as dangerous, then real work must be done to make it less dangerous. That is how perceptions are changed – by changing the basis for those very perceptions.

Recently I was lucky enough to travel to a city which has managed to do just that, and which could have some lessons for South African cities – Medellin in Colombia.

In the 1990s Medellin was the most dangerous city in the world, more dangerous than many active war zones. It was the territory of notorious drug lord Pablo Escobar.

Escobar – who is believed to be directly responsible for the deaths of about 40 000 people – was not the only tumour eating away at Medellin. Left-wing guerrillas and right-wing militias were also in the city, with running gun battles between these groups, drug gangs, and the army and the police being a common occurrence. At one stage, Medellin’s murder rate was nearly 400 murders per 100 000 residents – as a comparison, South Africa’s current murder rate is about 36 per 100 000. The city ranked as the most dangerous in the world today, Zamora in Mexico, has a murder rate of nearly 200 per 100 000 (the most dangerous city in South Africa is Cape Town, with a murder rate of 62 killings per 100 000 residents).

In much of the world, Medellin was a byword for violence.

Prosperity

Today, however, Medellin – while still not without its problems – is a prosperous, well-run city. The murder rate is about half of what it is in South Africa and poverty levels have also declined rapidly in the past twenty years.

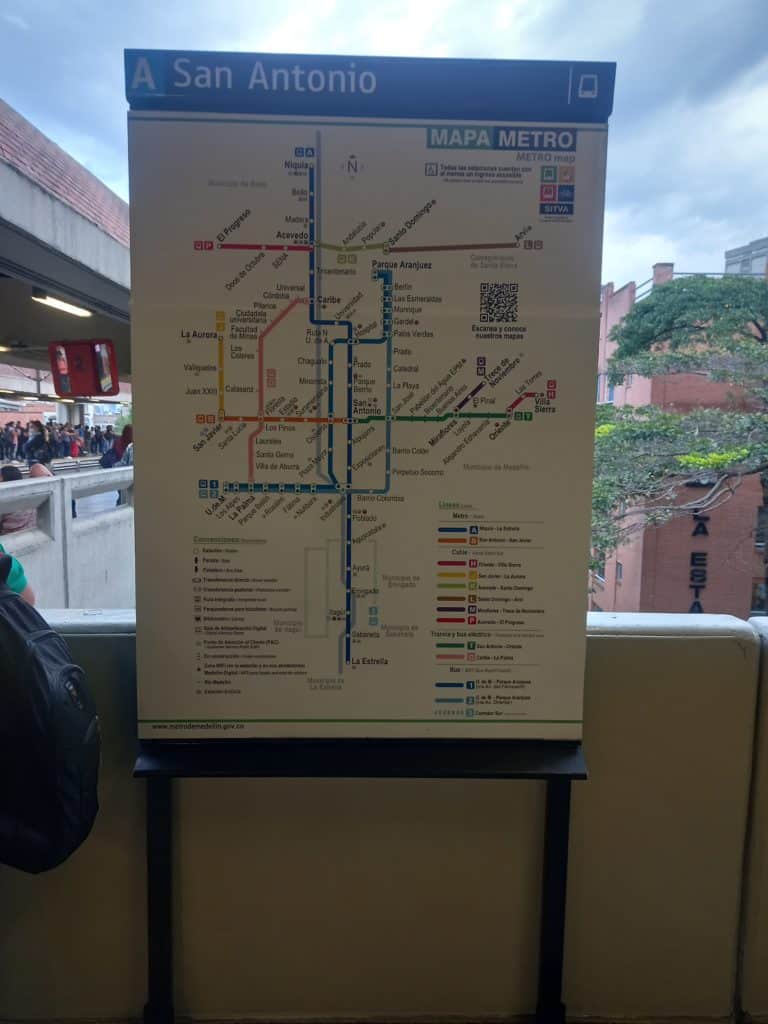

In addition, there is an innovative integrated public transport system, which uses buses, trains, and even cable cars to ferry the denizens of the city around, and is the equal of any public transport system I have been on in Europe. The cable car, one of the few cable car systems in the world which is used as ordinary public transport, connects the poorer areas of the city to the more affluent centre and other richer parts of Medellin. The poorer areas of Medellin are generally found on the steep hillsides surrounding the city, with a cable car being one of the few transport options that would work well for people living in those areas. For some people the cable car system has cut their average time to commute to work from about four hours to under an hour.

At the same time, the city constructed public, open-air escalators in the poorer areas of the city, saving people the effort of having to climb – literally – hundreds of stairs to get to different parts of their neighbourhoods. Some people had to climb the equivalent of 28 storeys to reach their homes, before the construction of the escalator.

There have been numerous other initiatives by the city’s government to bring opportunities to the city’s poor, such as opening libraries in impoverished areas, and opening community centres where people can learn English or French free of charge, or learn other skills.

Poverty has also declined drastically since the dark days of the 1990s. While poverty has seen an uptick as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic and resultant economic disaster, it is still below what it used to be.

Medellin is also welcoming to tourists, and is safe to walk around in at night, with lively nightlife districts boasting a wide variety of bars and restaurants to choose from. It’s a far cry from when Medellin was more dangerous than Mogadishu.

Of course, there are still problems. There are still large numbers of people living in poor housing, with shanty towns remaining a feature of the city. Walking from a park where sculptures by Fernando Botero, a beloved Colombian artist, are displayed to the city’s metro, I was reminded of the times I have had to navigate my way through the less salubrious parts of Johannesburg.

And although prostitution is legal in Colombia, there is a growing problem of human trafficking, and of people, especially minors, being forced into the trade against their will. Posters warning foreigners that if they are caught with a minor they will face the full force of the law are common throughout Medellin. And the crime rate has been inching up in recent years, although it is a far cry from the blood-soaked years of the early 1990s.

And while the influence of the various paramilitaries, gangs, and left-wing militias, have been successfully countered, there are still parts of the city where these groupings have more authority than the state.

Revitalisation

But how did Medellin achieve its successes?

Some of the revitalisation of Medellin was thanks to the overall renaissance of Colombia itself, which in the past twenty years has been one of the fastest-growing economies in Latin America.

Successive Colombian governments have worked to make the country safer and to break the power of organisations such as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), a left-wing guerrilla group, which laid down its arms following a key 2016 peace deal.

In addition, governments have worked to make the country attractive to investors. These measures have seen average per capita GDP in Colombia (at constant 2017 US dollars at purchasing power parity) grow from US$9 000 in 2000 to nearly US$15 000 in 2020 (South Africans were on average richer than Colombians in 2000 but were overtaken in 2015 and still remain behind Colombians).

Of course, these governments have not been without fault, and have been accused of using violent, extrajudicial tactics to break the power of the various militias and guerrillas. In addition, many Colombians have felt left behind by Colombia’s 21st century development. This saw a former Marxist guerrilla Gustavo Petro elected Colombian president just a few weeks ago, making him the first socialist to become leader of the country. It remains to be seen what changes he will make.

But much of the success in Medellin has been because of the residents themselves, as well as the politicians who have worked in the city.

The extension of public transport networks to the poorer areas of the city, while also ensuring that sustainable public spaces were built in these areas (a policy known as ‘social urbanism’ in Colombia), went some way to breaking the cycle of violence, and making sure public spaces were places where people could come together, rather than sites of conflict. At the same time, ‘participatory planning’ – where communities are heavily involved in development – became key to the revival of Medellin (as well as other Colombian cities).

Said influential former mayor Sergio Fajardo: ‘When you go to the poorest neighbourhood and build the city’s most beautiful building, that gives a sense of dignity.’

Inclusion and participation

Successive Medellin mayors, notably Fajardo, an independent who was first elected in 2003, have worked to ensure that governance in the city is not simply a matter of ‘top-down,’ where the concerns of residents are not heard, but rather ‘bottom-up.’ Residents, through interventions like ‘participatory planning’, are truly involved in the governance of the city and its development.

Fajardo also managed to break often corrupt networks in the city to enable Medellin to be run well for all its residents (although it was also not uncommon for deals to be made with drug gangs which still run parts of the city to allow city officials to meet with residents).

The example set by Fajardo has generally been followed by his successors as mayor, who have been politicians who put the needs of the city and its residents first, rather than themselves or the political movements they represent.

There are lessons for South Africa’s local governments in Medellin’s rebirth. Residents must be put first and cities must not simply be seen as troughs for people who now believe it is their ‘turn to eat’. A real effort must be made to develop our poorer areas and bring them into the life of the city; even parties which claim to be for the ‘poor’ only pay lip service to developing our most impoverished areas. We cannot continue to do things the way they have been done.

And in identity-obsessed South Africa, on initial evidence it seems that it is two white males who are copying (if inadvertently) what was done in Medellin – Geordin Hill-Lewis in Cape Town and Chris Pappas in uMgeni in KwaZulu-Natal. It’s early days into their administrations, but their initial successes could be a sign of what is to come.

And if their example spreads, perhaps Johannesburg or Ekurhuleni could join Medellin as examples of how a city stopped the rot and became a place people could be proud to call home.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend

Image by Ulises Casaraz from Pixabay