The older I get the more I am persuaded that the best reason for monuments is being reminded just how wrong we so often are about history.

Not that monuments are always effective mementos – which is one reason why, to be honest, I have never really felt especially outraged at the impulse in society now and then to tear down this or that statue. In a piece in September 2020, I touched on the less panicked way of viewing these things that was set out by former British Conservative Party MP – and, incidentally, South African-born – Matthew Parris. in his thrillingly iconoclastic article in The Spectator.

Who can resist cheering, at least inwardly, at Parris’s description of the statue of brutish slaving magnate Sir Edward Colston being ‘drowned by Bristolians in Bristol harbour [as akin to seeing] art come out of the galleries and textbooks and tourists’ snapshots, and into our hearts and spleens’?

This is, after all, the gist of our bearing approving witness to the toppled Stalins and Saddams of more recent times. And yet – perhaps even in those cases – I would, on balance, rather see monuments kept; most of us need all the reminding we can get about what really happened in ages (or even just decades) past.

And, anyway, isn’t it chiefly the tearer-downers, and those who applaud them, who are usually the ones most in need of reminding, or most prone to amnesia?

I am sure most of us would like this to be true, but I don’t think it is. Leaving monuments standing, it turns out, is no guarantee that they will prod us into making an effort even to at least try to get the history right.

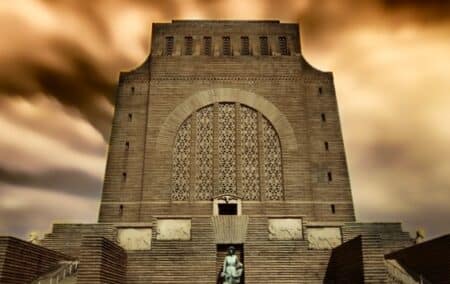

Recent skirmishing in the Daily Friend comments section about the Voortrekker Monument and what it really stands for is a case in point.

Some rather cross reactions to the reference in this recent piece by fellow writer Ivo Vegter to ‘the hulking memento of apartheid that is the Voortrekker Monument’ prompted me to go back to some 70-year-old news reports (in a modest personal archive that dates back to my assembling a book in 2007 on the 150-year history of the Cape Argus newspaper) to see what light they might shed on the topic.

Unsettling

My archive is limited, but it nevertheless shows just how unsettling the record can be.

The first of two news reports from 16 December 1949 (the day on which the monument was ‘consecrated’) errs on the side of journalistic sentimentalism.

The headline is creditably plain: ‘Voortrekker Memorial Consecrated’. What follows is rather different.

The fact that, all these years later, it can be so readily classified as ‘journalistic sentimentalism’ does, in a not insignificant way, tell us something of the scale and meaning of the event in its time. (And I am sure that it wouldn’t take me long to find some similar ‘journalistic sentimentalism’ under my own name from, say, the mid-1990s, which I might be tempted to try to disown today, and of which I might hope that a level-headed reader would be prepared to go as far as saying, ‘Well, it does tell us something of the scale and meaning of the event in its time.’)

This is what that first story had to say:

Amid solemnities on a scale so vast and impressive that they will be remembered forever by the vast multitudes who witnessed them, the memorial to the Voortrekkers on Monument Hill was consecrated today.

It is estimated that more than 100,000 people took part in the ceremonies, which were the climax of the four-day festival.

The supreme moment came at a signal from the Prime Minister (Dr. D. F. Malan) in the amphitheatre, after a three-minute pause in which the whole nation joined. The portals of the shrine swung open as the first stroke of noon chimed from the Union Buildings, and a golden circle of light shone on the words “Ons vir Jou, Suid-Afrika,” engraved on the sarcophagus.

Organ chimes rang through the solemn silence of the crowds standing reverently in the amphitheatre and on the surrounding hills.

No such thing

We can be fairly certain that there was no such thing as ‘the whole nation’ joining in any three-minute pause; if there was any doubt about the concept of ‘whole nation’ in late 1949, it was settled once and for all just a few months later with the Population Registration Act of 1950.

And it is in this context that the second news report of 16 December 1949 casts the monument in the role that was inescapably created for it.

The date itself is meaningful: 16 December – Day of Reconciliation today – was Dingaan’s Day in 1949, and would go on to become, first, Day of the Covenant, then Day of the Vow. It commemorated the Voortrekker victory over the Zulus in an 1838 engagement the Voortrekkers called the Battle of Blood River. The victory on the part of the 470-strong Voortrekker party against Zulu forces running to tens of thousands became a symbol of Afrikaner nationalism, and, among many of its adherents, of divine approval for their mission.

The headline of the second report exploited National Party Prime Minister D F Malan’s phrasing, turning history to metaphor: ‘South Africa still on the trek road’.

The following is an extract:

It was intended that when the present generation and future generations looked on the Voortrekker Monument they should ask themselves the soul-searching question, “Whither South Africa?” said the Prime Minister (Dr. Malan) at the inauguration of the Voortrekker Monument today.

South Africans were called on to build on the foundation laid by the Voortrekkers; South Africa was more than ever on the trek road.

“With deep respect and thanksgiving,” he said, “we now pay tribute to the Voortrekkers for the tough perseverance and heroism which enabled them, in spite of the greatest privations, to lay the foundation for a White Christian civilization in a greater South Africa.”

As a heritage the Voortrekkers had left them a greater South Africa at the cost of great sacrifices.

The soil on which they had to build their new future was bought by them with their own privations, heroism and blood sacrifices. Further, there was the realization that as bearers and propagators of Christian civilization they had a national calling which had set them and their descendants the inexorable demand on the one hand to act as guardians over the non-European races, but on the other hand to see to the maintenance of their own White paramountcy and of their White race purity.

Some of Vegter’s critics in the last while described the monument as a symbol of the fight against colonialism. Most of his critics rejected any suggestion of an association between the monument and apartheid.

Not much wiggle room

The above extract does not leave much wiggle room for avoiding the conclusion that the monolithic edifice consecrated in 1949 to the memory of the pioneers who set off for the interior of southern Africa rather than submit to British authority (and the emancipation of slaves) in the 1830s, functioned as part of the Nationalist apartheid project, and was meant to. Nor is there any sign here of the anti-colonial sentiment some suggested the monument was invested with, even if the more rabid Afrikaner nationalists then and in ensuing decades detested the British (not without reason, it may be said), and were not especially fond of English-speaking South Africans either.

In Malan’s own conception, the monument – which, like the temple it resembles, seems to induce reverence and similar worshipping impulses – was a ‘tribute to the Voortrekkers for the tough perseverance and heroism which enabled them, in spite of the greatest privations, to lay the foundation for a White Christian civilization in a greater South Africa’.

As is so often the case, however, smug vindication would almost certainly be misplaced.

While there is no doubt about what the Voortrekker Monument stood for among the most fervent – and, at the time, ascendant – Afrikaner nationalists of the late 1940s, a telling counterpoint in my archive to the meaning of the Voortrekker legacy comes in a news report from some years later, in 1956.

This brief article was about convoys of Black Sash members from around the country converging by road on Cape Town under the auspices of the Women’s Defence of the Constitution League, in protest against the National Party’s dogged (eventually successful) efforts to erase entrenched clauses in the Constitution in order to remove coloureds from the common voters’ roll.

‘V for Victory signs’

That news story of 1956, headlined ‘Victory signs greeted Black Sash cars’, told of how the Black Sash women on their drive to Cape Town were greeted by ‘V for Victory signs, thumbs-up salutes and warm congratulations offset by occasional taunts like “vuilgoed”’.

That was to be expected, presumably. Mrs M M Hitchman of Kimberley described being told by a man who confronted them at the hotel in Worcester where they were resting: ‘We would like to push you into the sea.’

Even so, said Mrs Ruth Foley, national president of the Women’s Defence of the Constitution League (later known simply as the Black Sash) commented: ‘On the whole we received a lot more approval than we expected. At some Karoo towns we were wished well by people who could scarcely speak English.’

For me, most striking of all are the two paragraphs of this news report devoted to ‘one Free State car [containing] a party from the Welkom branch driven by Mr P J Pienaar whose wife had persuaded him to drive them down’.

Mrs Pienaar is quoted as saying: ‘We are an old Free State family. Our people came up with the Voortrekkers. I feel deeply religious about this; I feel that we are in danger of losing something we may never recover.’

South Africa’s apartheid catastrophe was nearing the end of its first decade, and there is little doubt Mrs Pienaar’s anxiety was well-founded.

Just a week earlier, the Cape Argus had said in an editorial: ‘By the time these words appear in a print, the joint sitting will doubtless be nearing its end, and the Separate Representation of Voters Act will have been validated by the two-thirds majority artificially contrived for the purpose.… What has happened to-day is not a beginning but an end. It is the end of faith in the White man’s word, the end of the entrenched sections, the end of the aspirations towards unity based on the agreement of Union. Henceforth, South Africa will live, but with honour tarnished. Every promise made by the White man to the non-European or by one White section to the other will, in future, be read in the light of the pledges given in 1931 and 1936 and scattered to the winds to-day.’

Almost implausible

Looking back, it’s almost implausible that anyone in the 1950s would have invoked their Voortrekker heritage in asserting a position counter to Afrikaner nationalism.

‘For all that has happened since,’ I wrote of the Pienaars of the Free State just a few weeks ago in Business Day, ‘this long-forgotten news report of 12 February 1956 has something meaningful to tell us about SA — then, and now.’

What might that ‘meaningful’ thing be?

It is almost certainly a multiplicity of things, the most obvious of which is that stereotypes seldom serve us well, and that – for instance – ‘Voortrekker’ always meant a great deal more than we might have appreciated.

I think that news report from the summer of 1956 also implicitly challenges us to doubt and challenge the impulses of political activism that is willing to exploit our attachments and affections at any cost, for its own ends – but also to check ourselves whenever we are tempted to countenance fibs or gloss over infamy that may be inconvenient to our cause.

Misplaced pride, no less than misguided activism, has a way of poisoning the past and spoiling the truth of the long and difficult stories that none of us can detach from our present and still hope to preserve an authentic sense of self.

The context of my recapitulating the story of the Black Sash convoys last month was the curious saga of Ryanair and its Afrikaans ‘citizenship’ test.

Here was a furore that couldn’t have happened at a more ticklish moment, as democratic South Africa half guiltily remembered the 16 June 1976 Soweto Uprising – against Afrikaans tuition – on a 2022 Youth Day marked by shocking disregard for the plight of the jobless and under-educated millions who make up the country’s all but abandoned youth cohort.

The faintly bizarre Ryanair affair did, not unsurprisingly, bring out some residual antipathy towards Afrikaans for its having been (turned into) the amptelike taal of apartheid.

Over the years, I have come to appreciate that it is, and I think always was, so much more than that.

Far worthier monument

The extraordinary and evolving story of Afrikaans is something I have written about before. Though it came much later than the Voortrekkers, and was initially disparaged by the worthies of the time as kitchen Dutch, a language of and for the servants (who did much, of course, to develop it in its earliest years, and whose descendants remain among the language’s most creative linguists today) – Afrikaans is perhaps a far worthier monument to the complex story of post-Van Riebeeck pioneering in Africa.

And the Ryanair controversy did cast some light on the scale and quality of what is a somewhat fluid ‘monument’, and one that claims attention principally for its vitality and dynamism.

I am thinking, here, of South African-born BBC presenter Audrey Brown’s piece of 14 June, affectionate and angry all at once – difficult, demanding and not to be taken lightly – in which she writes of the ‘spitting rage’ rising in her chest when she read that ‘Ryanair was forcing South African passport holders to take a test – in Afrikaans – to verify that they were indeed South African’.

In that moment, she recalled, ‘I was so angry “ek kon slange vang”’.

Though enraged by the memory of the amptelike taal, it was to the Afrikaans ‘which … delights those of us who speak it’ that she turned to describe her complex emotions as a South African who is ‘black, of mixed heritage’, who grew up in the later years of apartheid, who resented Ryanair’s ‘demeaning’ tests, and yet who found that when this moment of anger subsided, it ‘gave way to a longing for home’.

And of this longing, she had a telling observation to make.

‘(The) word that captures that feeling best for me,’ she wrote, ‘is not homesickness or nostalgia. It’s the Afrikaans word “heimwee”’.

I have a hunch that Mrs Pienaar of Welkom, were she alive today, would understand this far better than I ever could.

[Image: Elmer van Zyl, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=28780875]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend