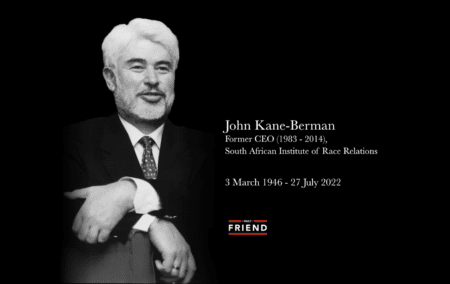

The unexpected death of former IRR CEO John Kane-Berman, at the age of 76, will leave a large hole in the liberal firmament.

One morning, some time around my 17th birthday in the late 1980s, the headmaster called me and five other pupils at Hoërskool President in the south of Johannesburg to his office.

All top academic performers, we had been selected to go on a trip to the Pilanesberg Game Reserve, with similar teams from six or eight other schools.

Our group was all white, of course. Education, like most everything else, was strictly segregated by race throughout my school career.

The outstanding feature of this trip was that only one of the other participating schools was a whites-only school. The remainder represented Indian, coloured and black children.

The idea was to introduce pupils from different races to each other, by taking them on a camping trip where they would interact with each other, have conversations about their life experiences, cook traditional meals for each other, and learn that we were not so different, after all.

For the white kids, trips to game reserves were not a novelty. For the others, however, a whole new world opened up. Over just a few days, bonds and friendships were kindled across racial lines as we walked with rhinos, ate together, and sang around the campfire.

Non-racialism

It wasn’t my first introduction to non-racialism; that happened when I was 12, when a Dutch aunt of mine travelled to South Africa to research a thesis on multi-racial churches under apartheid, such as St. Mary’s Anglican Church in Johannesburg and Regina Mundi Catholic Church in Soweto.

It was, however, a rare visit across the barriers of ‘separate development’ that the government had worked hard to maintain, and this time I was old enough to contemplate the injustice of racial segregation.

Soon enough I would encounter both the ‘Swart Gevaar’ and the ‘Rooi Komplot’ at close quarters at Wits University.

Another year later, the ANC, PAC and SACP were unbanned, and Nelson Mandela was released from his 27-year incarceration. South Africa was on the path towards a new political dispensation, and as a student at a multi-racial university, I had a front-row seat.

With hindsight, the idea of introducing promising schoolchildren to their counterparts across racial lines in the 1980s was inspired and influential.

It primed me to deal with the fairly traumatic realisation that much of my schooling consisted of government-sponsored indoctrination and racist conditioning, and that I had been lied to by the adults I was taught to trust and look up to.

The cross-cultural trip was an initiative of the South African Institute of Race Relations (IRR), then under the leadership of John Kane-Berman.

Magisterial

It would be quite a while before I again encountered Kane-Berman, or the Institute. In those years, I was a technology journalist, which largely kept me out of South Africa’s political and public debate.

I was a voracious reader, though, both of newspapers and thick, serious books. I read a lot of history. I explored various political philosophies to broaden my horizons beyond the Christian National Education the apartheid government had foisted upon us. I had learned some economics in a bid to comprehend the so-called new economy of the dotcom boom, and the subsequent bust which proved it to be a just the same old economy supercharged by easy money.

Just about when I embarked on a new life as a columnist, starting with Maverick magazine in the mid-2000s before it became the Daily Maverick, I was fortunate enough to attend a gala event hosted by the Institute for Race Relations.

The highlight of the evening was a magisterial speech by John Kane-Berman.

His command of South African politics and history, his facility with research and data, his commitment to theoretical and practical justice for the poor, and his classical liberal analysis of the country’s trajectory all made a profound impact on me.

He was an intellectual heavyweight, who spoke with conviction of the ideal of non-racial freedom towards which I had also gravitated. I was impressed, and not a little intimidated.

Principled

Kane-Berman was as principled in his liberal critique of ANC governance as he had been as a vocal and highly influential critic of the apartheid government.

This was refreshing, in the face of what Jill Wentzel had called the ‘liberal slideaway’ of the 1980s, when anti-apartheid liberals were loath to be seen criticising the new, democratic government, for fear of being painted as right-wingers or unreconstructed racial nationalists.

Many more interactions with the IRR would follow, including several commissions to write articles and research reports, which would ultimately result in my becoming a columnist for the Daily Friend in March 2020.

A generation older than I am, Kane-Berman laid the groundwork for that all the way back in 1988. He had been a journalist himself, and a compliment from him would feel like a major accolade.

Thriving

Others knew Kane-Berman and his work much better than I did. His monumental contributions to the liberal cause in South Africa, over a period of over 50 years, including his role in ensuring that South Africa’s Constitution is broadly liberal in character, are detailed in a Daily Friend obituary which I can highly recommend.

The cause of classical liberalism is thriving in South Africa, in large part because of Kane-Berman’s inspirational work in building and developing the Institute over the 31 years he led it between 1983 and 2014. He has left an immense legacy, and South Africa owes him an enormous debt of gratitude.

There is a large hole in the firmament where John Kane-Berman’s star once shone, but the ideas to which he committed his life and for which he worked tirelessly will long outlive him.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend