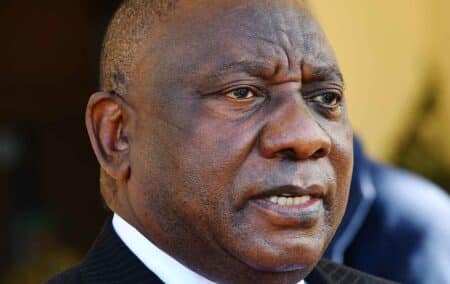

In his State of the Nation Address, President Cyril Ramaphosa committed to forging a social compact between South Africa’s economic role-players to ‘grow our economy, create jobs and combat hunger.’

This, he said, would be put together within 100 days. This timeframe – unrealistically ambitious in view of the scale of the challenges – was missed in May, and a revised goal of 100 working days came and went in June.

Nevertheless, achieving such an agreement remained the government’s intention, and last week, the President returned to this theme in his weekly newsletter. Among other things, he stressed that there would need to be ‘trade-offs’ between business and labour. He added: ‘As the name implies, a new consensus can only be successfully implemented if there is full agreement on a common objective, the plan to achieve it, and a commitment by all partners to the plan’s implementation.’

Social compact

The point of a social compact is to build a system that operates efficiently and effectively to the overall benefit of all. To do this, there is a process of compromise where each party would sacrifice something in order (hopefully) to gain some advantage more important.

Precisely what has been placed on the table is uncertain, but media reports have described a government-authored document that foresees three sets of concessions and commitments. Government would accelerate its economic reforms; commit to reducing red tape; improve the operations of state-owned enterprises; take action against corruption; expand the presidential employment programme; fill vacancies in the public service; and expand social security.

Labour would ‘support’ reforms to the labour market, especially the restructuring of the labour market, particularly to make concessions for small and medium-sized businesses and the restructuring of state-owned enterprises; endorse multi-year wage agreements in the public service; and work towards keeping entry-level wages to global averages.

Business, it seems, would agree to targets in investment, employment; limiting retrenchments; restricting increases in executive pay; and appointing workers to company boards. There are also suggestions for higher tax levels to fund expanded social security payments.

Further reports indicate that the framework document has not been well received by either business or labour. Labour has predictably decried the prospect of revising any of the protections it enjoys, throwing in for good measure ‘the right to have their wages protected from erosion by inflation.’ This is a long-standing position with its various iterations stretching back to the 1996 Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) strategy, and its proposals for ‘regulated flexibility’.

Organised labour has fought its corner tenaciously, which – together with the political heft that the Congress of South African Trade Unions has exercised as part of the ANC’s alliance – has meant that it has by and large been able to prevent any significant labour market reform.

Complaints

Business has complained about the government’s approach to this scheme – with no timeframes, systems or processes, according to Business Unity South Africa head Bonang Mohale. It’s also been reported that BUSA is seeking a mandate from its members to reject the proposal, as some of its features are both unworkable and inimical to its interests.

The formal positions held by business, such as the need for greater flexibility in the labour market, have been well known and articulated since at least the South Africa Foundation’s Growth for All document of early 1996. However, business organisations have tended to be cautious in pushing too hard for them. A report in News24 made the observation: ‘In the past, business engaged in compacting processes in the interests of good relations, even when they believed there was little to gain. The mandate from members to reject the framework document marks a hardening of its attitude.’

The prospects for an all-encompassing and game-changing ‘compact’ appear slim indeed.

And while it is at least clear what labour and business are being asked to sacrifice, the same cannot be said of the government. From what has been reported on the matter, the government’s role seems largely to carry on as before, only better. So, it offers accelerated structural reforms. What exactly these will entail has not been specified, but this is hardly a fresh commitment. Reform has been a buzzword invoked since President Ramaphosa’s accession to his office, and even before: it was central to the entire National Development Plan that received such applause a decade ago. In 2019, the President conceded in an interview that his reform agenda was on a limited time window. (How long was available to him? ‘Not long,’ he answered.)

Yet for all this, not a great deal has been achieved or even initiated. The power crisis has seen some movement – the recently announced energy plan outlines official thinking – although this came in the wake of catastrophic waves of load-shedding, and has been accompanied by some frankly quixotic suggestions, such as establishing a second Eskom.

Red tape

Cutting red tape, meanwhile, has been on the official agenda since the 1980s, articulated in remarkably similar terms by heads of state since PW Botha. President Ramaphosa assured the country in his State of the Nation Address in early 2020: ‘We are removing red tape to reposition our economy, working with the private sector and with labour to address the specific blockages that hamper the growth of companies.’

Earlier this year, the President announced the creation of a unit in the Presidency to tackle this issue.

Dealing with SOEs and combating corruption? This repeats promises made so often that it’s doubtful a comprehensive list could be compiled. Besides, these were promises implicit in the President’s ‘New Dawn’, and explicitly repeated subsequently (and routinely beforehand too).

Perhaps the question to ask in all this is whether there is any sensible alternative to taking these steps. Could one make a case for not undertaking ‘reform’, for ignoring (if not adding to) red tape, for watching passively as SOEs decline further into ruin and for corruption to rampage unchecked? In saying this, one is not suggesting that government action can be expected to be decisive and effective – and experience is a warning that very little may be done at all – but that in framing its contributions in these terms, the government is offering nothing that it has not already offered and nothing that sheer common sense would not dictate.

It’s not clear what the government is offering while it asks its ‘social partners’ for concessions.

Political capital

One thing that the government does have, albeit in diminishing quantity, is political capital. This is held both by the government (understood as the formal administration) on behalf of the constituencies that support and have benefited from its policies, and by the ANC, which has used (in many respects, abused) the state for its own purposes. Each of these could have something important to offer in making real, substantive change to policy and governance practice – and in doing so, making South Africa an attractive place to do business.

One idea would simply be to renounce the idea of Expropriation Without Compensation (EWC). A great deal of damage was done to South Africa’s image in recent years by the reckless EWC drive, through the proposed constitutional amendment and the Expropriation Bill. The government’s own investment envoys said that this was undermining their message. And meddling with the Bill of Rights sent a disturbing message about the future of constitutional governance in South Africa.

Besides, this offered nothing to deal with the challenges of land reform, which had more to do with administrative incapacity than with a lack of state power.

EWC must be unambiguously renounced, and solutions sought that expand property access and the landed economy – the IRR has published proposals aimed at doing just this. Unfortunately, EWC remains an ANC commitment, and President Ramaphosa referred to it in his address to the party’s Policy Conference. Not only should the EWC drive continue, he said, but it was an instrument ‘that we must utilize’.

A second is in the field of empowerment and affirmative action demands. These impose costs on investment and specifically on employment. If there was any doubt about this, consider the fact that Eskom needed an exemption from empowerment regulations for its procurement. And was granted one.

This would be politically tricky, as these policies have been essential for building key support bases for the ANC and supporting its patronage system. And they constitute a central part of the party’s ideological outlook, providing specific benefits to a racially defined constituency. Indeed, the President has said that if anything, empowerment policy must be made more intrusive, while amendments to the Employment Equity Act awaiting the President’s signature will not only empower the minister to set quotas but impose crippling penalties for failing to comply. This will quite predictably disincentivise employment, or even discourage business operations entirely.

Costs

South Africa simply cannot afford the costs these policies are imposing. The obvious solution is to radically scale back these requirements, or dispense with them altogether. The IRR has proposed an alternative framework, Economic Empowerment for the Disadvantaged, which would seek to encourage and incentivise productive and responsible business activity geared at the upliftment of the country’s poor.

Thirdly, the public service must be professionalised. While this is supposedly part of the government’s reform agenda, it is rendered moot by the continued commitment of the ANC to the practice of cadre deployment. More than anything else, cadre deployment has retarded the emergence of a professional and developmentally oriented public service and has made a nonsense out of the professed ambition to make South Africa a developmental state.

Cadre deployment also featured prominently and was condemned unambiguously by the Zondo Commission as not only illegal and counter-constitutional, but as a contributor to corruption. Once again, though, it is key both to patronage politics and the ANC’s ideological worldview – a form of ‘state capture’ in its own right – and is a deeply entrenched part of the conduct of its politics. The Report of the Commission offered an opportunity to step away from it with some dignity, but both the party and the government have chosen to fight a challenge to cadre deployment in court. This is a tragedy that shows just how serious South Africa’s malaise is.

Committing to action on these three initiatives would signal that the government is in earnest about changing direction. Acting on them would demonstrate that it is willing to make a real contribution to setting the country to rights. The credibility that would build would be an asset arguably more important than a shaky ‘social compact’ that promises a great deal with little prospect of delivering much at all.

It would signal that government is a partner for the country’s development, rather than a primary obstacle to it. Who knows, it might even make ‘concessions’ from others look like a reasonable deal.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend