A little earlier this year, the government held yet another Communal Land Summit, which, over one-and-a-half days, consisted of four ministerial speeches, instructions on how to ignore the Motlanthe Commission recommendations, several commissions, and two lunches.

Unsurprisingly, since she first practised as Minister of Land Affairs 20 years ago, Thoko Didiza’s post-summit SABC interview was a masterclass in how to deflect awkward questions. Deputy President Mabuza’s defence of the enterprise that it was ‘not a lot of hot air’ was perfectly correct – it did not even qualify as hot air.

Whether any communal land right holders were present was not reported.

In this context, it is instructive to note that, in terms of land law and land use, Transkei is not part of South Africa. Crucial laws are either not repealed, not applicable, or have not yet been enacted, or the province has no jurisdiction.

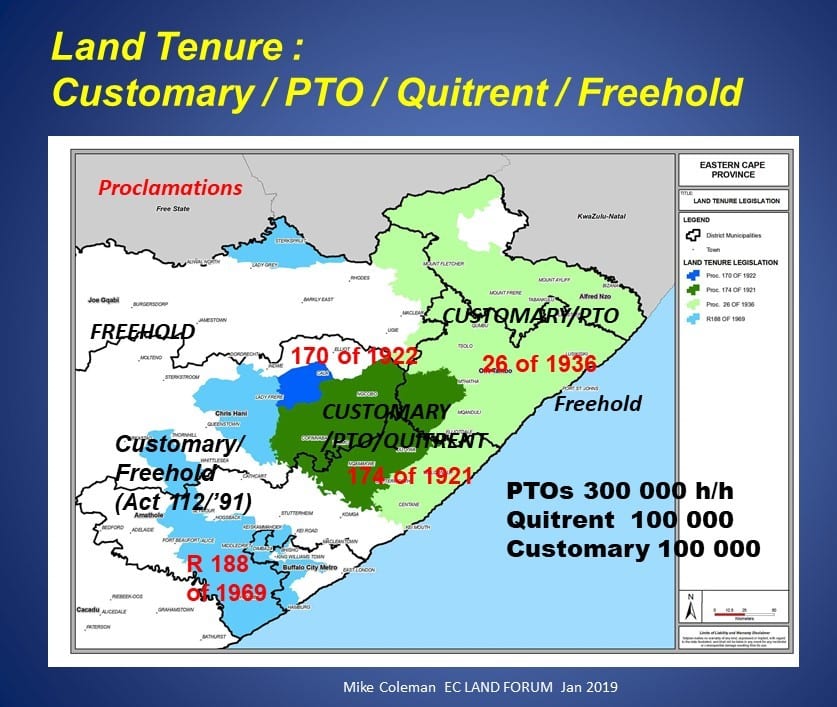

In rural Transkei, 1936 Native Trust and Land Act is still in force. So are quitrent Proclamation 227 of 1898, and land tenure Proclamations 174 of 1921, 26 of 1936, and 170 of 1922.

The Upgrading of Land Tenure Rights Act (ULTRA) of 1991 is still not applicable to Transkei. Rural planning law was repealed in 1998 but not replaced; even now after a 20-year vacuum, the Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act (SPLUMA) has inadequate provisions for communal land.

In summary, land tenure ‘Permission to Occupy (PTO)’ proclamations that have not been repealed, are still in force, though have not been administered since 1996 are:

Proclamation 26 of 1936 (unsurveyed districts)

Proclamation 174 of 1921 (surveyed quitrent districts)

Proclamation 170 of 1922 (Xalanga District)

Proclamation 11 of 1922 (Trading stations) and

Proclamation R 188 of 1969 (Herschel District)

There are three legal forms of land tenure in Transkei: approximately 300 000 Permission to Occupy (PTO) certificates, 70 000 quitrent titles in the nine south-western districts, and between 150 000 and 200 000 customary allocations by traditional leaders.

The land administration system for land tenure in all 26 districts was destroyed in 1996 by national government, leaving a vacuum to be filled by illegal corrupt land allocation by both criminal chance-takers but also by some traditional leaders.

The Minister of Land Affairs (now of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development) refused to administer the land tenure Proclamations that, being unrepealed, are still in force, but in 28 years there has been no communal land tenure reform to replace the PTO tenure proclamations.

Consequently, although every department, municipality, politician, traditional leader, community activist, land-right holder has legitimate interests in land, none have any legal authority over land tenure.

The Eastern Cape Premier has no authority over Transkei communal land; land is a national competence, so after 1996 one office with minimal staff in Mthatha supposedly replaced 26 district land administration teams located within reach of local land-right holders and with authority over land.

The land restitution cases in Transkei, such as the very first awarded by Deputy President Zuma in 2001 at Dwesa-Cwebe, still have no title deed.

There are serious practical consequences to the lack of land reform and administration.

For example, Sterkspruit informal residents cannot be legally serviced by their municipality or Eskom because they are on communal, not municipal, land. King Sabata Dalindyebo Municipality cannot develop Coffee Bay into a thriving Wild Coast town, because communal land cannot be legally transferred to a municipality. Without land reform there are no land unit boundaries and no owners of land, so SPLUMA can hardly be applied.

Still not applicable

After 30 years, two amendments and three Concourt cases, ULTRA, the 1991 law on land tenure rights, is still not applicable in Transkei. In contrast, in Ciskei – which was under different law – all quitrent tenure has been converted to freehold. In Transkei approximately 70 000 quitrent titled properties in nine magisterial districts remain in limbo, while ULTRA cannot be applied to communal land rights at all, unlike across the rest of South Africa.

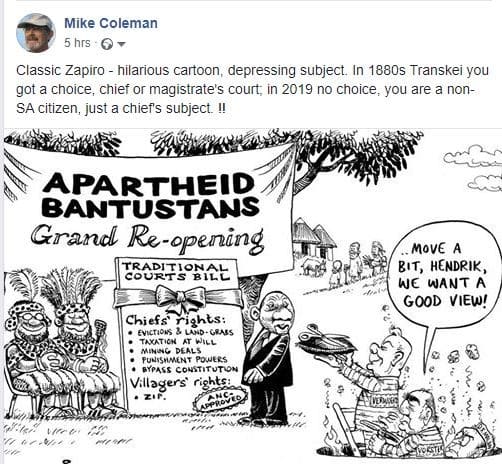

In addition, since 2000, a bundle of apartheid–era laws ensures Transkei rural dwellers are subjects of traditional leadership, not citizens of South Africa: Communal Land Rights Act (found to be invalid by the Concourt), Traditional Khoisan Governance Act, Traditional Courts Bill, State Land Development Act, and Communal Land Bill.

The following sums it up:

On the Wild Coast in the absence of any other effective agency or legislation, provincial Environment Affairs is the only authority. Its Transkei Decree 9 of 1992 is still in force and its 1 km-wide coastal conservation area therefore dominates and inhibits any development proposals. The lack of tenure reform and administration ensures absolutely nothing happens.

Obtusely, the provincial Green Scorpions, an effective unit, have been forbidden to tackle Wild Coast illegal sandmining by Gwede Mantashe’s national Department of Minerals and Energy, which has no capacity to do so.

No legal tenure

Most of the Wild Coast hotels have no legal tenure, other than ‘purported PTOs’ from the 1980s and consequently have seen little serious physical development in 30 years.

All of the above situations could be solved by a competent government department under a competent minister, or be delegated to the province if there were a similarly competent department and MEC. Then Transkei would become truly part of South Africa.

[Image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/michael_mayer/11309976286/in/photostream/]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend