Race is South Africa’s eternal fault line. Nearly everything in this country is viewed through the prism of race, from who our politicians are, and who represents South Africa in international sport, to who is reading and writing South African literature.

This should, of course, not be surprising. Race was for many, if not most, South Africans the key indicator of how their lives would turn out, and in many ways still is.

Many aspects of life in South Africa are seen from a racial viewpoint. This means that it is common for politicians to speak of ‘our people’ and explicitly mean black South Africans, or speak about the need to uplift ‘Africans in particular’.

At the same time, it is common to see claims on social media and elsewhere that ‘Africa is for Africans’, or that people of Indian or European descent should go ‘home’.

But in a country like South Africa, where people from all over the world have made their home over centuries, it is not so easy to define what an ‘African’ is.

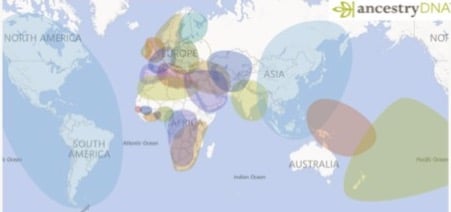

Ancestry test

I recently did an ancestry test, which gives you a breakdown of which parts of the world contribute to your DNA. While the result was mostly unsurprising (I am mostly a Western and North European mongrel, a result probably common to many white people who are descended from colonial settlers), I did have some ancestry from unexpected parts of the world. Some of my forebears came from Southern India, and others from South-East Asia – likely slaves who were brought to the Cape in the 17th and 18th centuries.

But I also had some ‘Southern Bantu’ ancestry, meaning that I have confirmed African ancestry. (Some will scoff and say this does not mean I can claim African ancestry – but ‘trust the science’, I say). This is actually fairly common among white South Africans, particularly Afrikaners. A recent study found that 99% of Afrikaners had some non-European ancestry, either from Asia or from Africa, in the form of Bantu or Khoisan ancestors.

Deciding who is an African thus becomes a bit more complicated. And this is before we get to the absurdity that official government nomenclature divides South Africans into four race groups – ‘Black Africans’, ‘Coloureds’,’ Indian/Asians’ and ‘Whites’. The absurdity comes in when we consider that the majority of coloured South Africans will have some (or a lot) of Khoisan ancestry, a group of people who are widely acknowledged as being South Africa’s ‘First Peoples’). Ancestors of what are today recognised as the Khoisan probably occupied what is today South Africa (and our neighbouring countries) as early as 150 000 years ago, far earlier than any other group that now calls the country home. But South Africans who are most likely to have Khoisan ancestry – coloured South Africans – are not designated as ‘Africans’ by the government.

And given the fact that South Africans are a pretty mixed-up bunch – genealogically speaking – can the continued use of race-based policies be justified?

Genetic testing

Some would argue, yes. Consider this bizarre statement by a BBBEE verification company which has suggested that South Africans could be subject to ‘genetic testing’. This would be to determine a certain threshold of African ancestry, and it could then be decided whether an individual is, in actual fact, black, for the purposes of B-BBEE verification.

Leaving aside the dystopian undertones of living in a place where your access to certain privileges (such as government contracts) could be determined through genetic testing, it is clear that policies such as B-BBEE have been failures. It’s time for the South African government to leave aside its obsession with race and try to uplift all South Africans who need it, rather than using race as a proxy.

There are some people who would have you believe that policies such as B-BBEE and employment equity are effectively ‘reverse apartheid’, and that whites in South Africa are now as oppressed as their black counterparts were during apartheid and before. Of course, nothing could be further from the truth.

White South Africans are still far more likely to be employed than other South Africans, they have – on average – higher incomes, and are more likely to have access to decent services, and so on.

That said, it is clear that policies such as BBBEE have distorted the economy and resulted in perverse outcomes. Just as apartheid resulted in all South Africans being poorer, race-based policies implemented by post-1994 governments, such as BBBEE, have done the same.

Now this is not the view of white reactionaries who hark back to some mythical apartheid golden age. This is the view of ANC luminaries and it is not a new view.

Speak out

The latest ANC stalwart to speak out against BBBEE and race-based policies in general was Barbara Hogan, a former minister of health in the Zuma administration. Speaking this week, Hogan said: ‘This policy has become an excluding thing where only people with political connections and status could benefit from policies, and the bulk of black South Africans remain unempowered. I think we need to take a hard look at what is excluding black South Africans from participation in the economy, but we have to get to where the real need is now.’

Hogan is not saying anything that senior ANC figures have not said before. Senior figures, from Pravin Gordhan to Mathews Phosa to former president Kgalema Motlanthe, have all remarked previously that BEE does little to help ordinary black South Africans and rather leads to distortions in the economy, while helping a small connected elite – exactly what Hogan and other critics of the policy (not least the IRR) have said.

Despite this, the ANC, and many in the media and chattering classes, cannot bring themselves to look beyond this racial prism, and envisage a new way of empowering South Africans.

The IRR has proposed a new way of empowering South Africans. Rather than using race as a proxy for disadvantage, disadvantage itself is used as the measure to determine beneficiaries. My senior colleague, Dr Anthea Jeffery, has done much work on this policy, called Economic Empowerment for the Disadvantaged (EED).

If more South Africans did an ancestry test as I did, we would find that we cannot delineate so easily who is what race and where someone’s ancestors were from, further reflecting the folly of race-based policy. For true empowerment, South Africa needs to ditch race-based policies that serve simply to benefit an elite. South Africa faces a dark future if this does not happen as a matter of urgency.