This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

19th August 1612 – The ‘Samlesbury witches’, three women from the Lancashire village of Samlesbury, England, are put on trial, accused of practising witchcraft

Fear of witchcraft, that is to say, fear of a small group of people from within the community with extraordinary powers working together to destroy the good fortune of others is something found in all human cultures and societies across the world.

This fear manifests in different ways across time and space, but always shares similar themes of malevolent people within our midst, whose destruction, if we can find them, will liberate us from any calamity imaginable.

From the ancient shamans sacrificing people to ward off bad luck to the burning of witches and even to the modern Satanic Panic or lizard-man conspiracy theory, witchcraft has always been with us and will always be with us.

While there is almost always a fear of witches, the intensity of this fear ebbs and flows across time and space. The Middle Ages in Europe, (roughly 500 –1450) is often erroneously believed to be a time of ‘superstition’ and ‘ignorance’, when the burning of witches and the driving out of demons were common occurrences. This is in fact a myth often created by Protestant Enlightenment thinkers who sought to contrast the new Age of Reason with an imagined past of barbarity and ignorance. While witch-burning did happen across Medieval Europe, it was on a small scale, with the Christian church authorities often intervening to put a halt to witch trials.

From the 10th century until the middle of the 15th century, the Church refuted the existence of witches, and in 1258 the Pope passed an edict forbidding trials for witchcraft. The Church held that belief in witches was irrational, and that God would not permit such evil to be done. Church inquisitors would often arrive in places where people had been accused of witchcraft, examine the evidence and declare the accused innocent.

This attitude changed around the time of the Protestant Reformation in 1517. Christendom became consumed by debates about the proper way to worship, the relationship of man to God and the structure of the Church. The Medieval Church, which had held together the disparate regions of western and northern Europe for centuries, fractured. Almost every country in Western Europe had some church reformers, some of whom were radical. Debate raged in pamphlets, in sermons, on the streets and often led to violence and division.

This was a time of fierce intellectual contest between Protestants (as they were soon known) and Catholics, who sought to expose the other side as blasphemers and heretics doing the work of the devil to divide the church.

It is in this period that Europe became obsessed, particularly in the Protestant world – less than 10% of all witch trials were in majority Catholic kingdoms – with witches and witch trials.

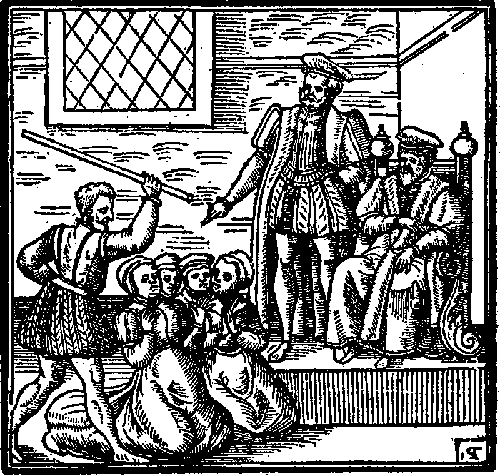

Accusations of witchcraft and the trials which went with them were often used by competing factions within a community to target and eliminate their enemies. The trials themselves were often a proving ground for particular theological outlooks where both sides used them as an opportunity to sway neutral Christians into their faction.

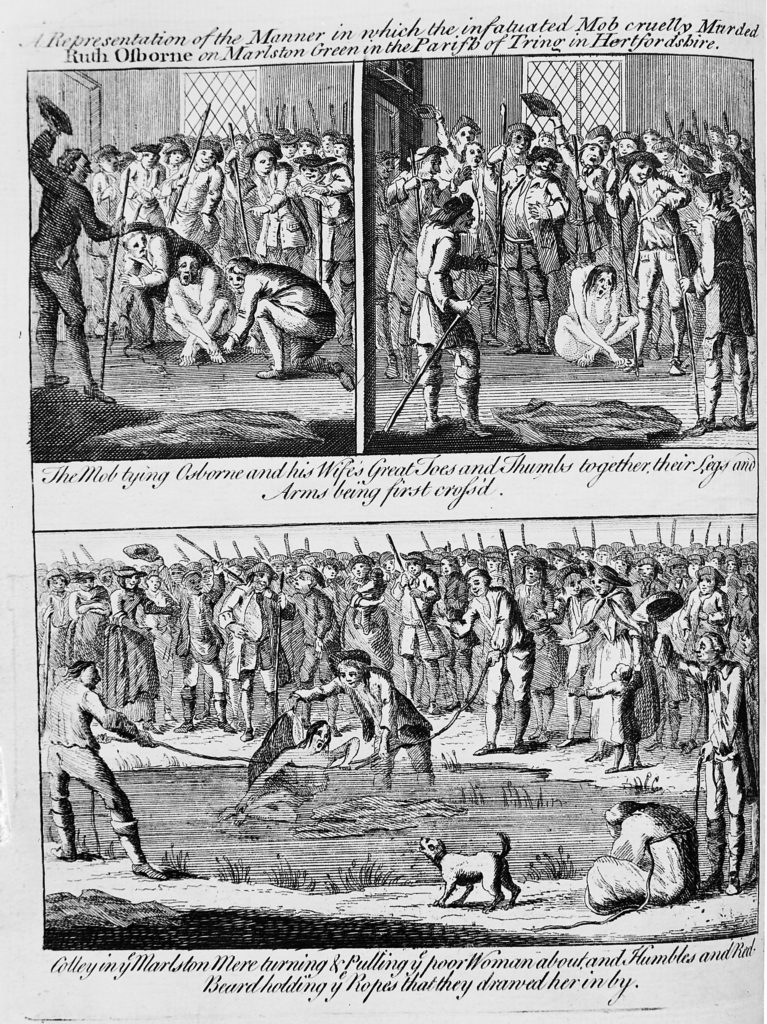

During the height of the witch-trial hysteria between 1450 and 1700, 800 000 people were accused and tens of thousands were executed for the crime of witchcraft.

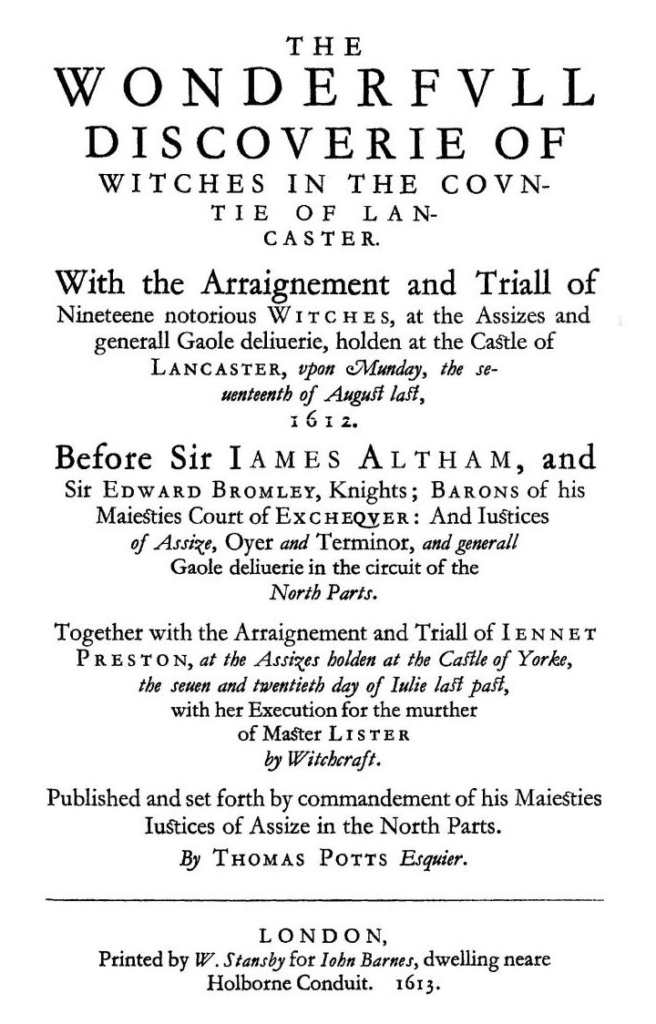

One of the most famous of these trials was the case of the ‘Samlesbury witches’ in England, around the village of Samlesbury in Lancashire. At the time, England was ruled by King James the First, who was a strong believer in witchcraft.

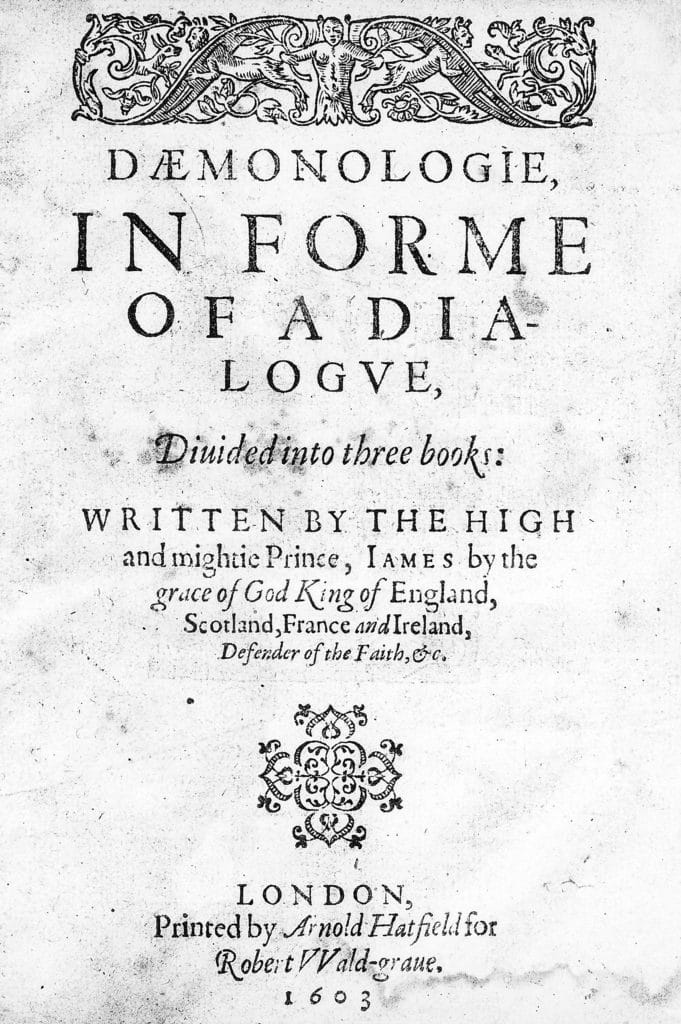

During his time as King of Scotland, James had become convinced that witches were plotting against him and in 1597 he published a book called Daemonologie, which laid out ways to detect witches and destroy them.

The opening passage of this work reads:

The fearefull aboundinge at this time in this countrie, of these detestable slaves of the Devil, the Witches or enchanters, hath moved me (beloved reader) to dispatch in post, this following treatise of mine (…) to resolve the doubting (…) both that such assaults of Satan are most certainly practised, and that the instrument thereof merits most severely to be punished.

His works encouraged witch-hunting hysteria and it was in this climate that the Samlesbury trials took place.

In 1612, three women, Jane Southworth, Jennet Bierley, and Ellen Bierley were accused of witchcraft by a 14-year-old girl, Grace Sowerbutts and were put on trial on 19 August 1612. The three women were accused of ‘diverse devillish and wicked Arts, called Witchcrafts, Inchauntments, Charmes, and Sorceries, in and upon one Grace Sowerbutts’, and all three pleaded not guilty.

Grace was the primary witness for the prosecution.

During the trial, Grace claimed that the defendants were able to transform themselves into dogs, had eaten a baby, convinced her to drown herself and summoned demons with whom they danced and had sex.

When the time came for the defendants to give evidence, they cross-examined Grace and some of the other prosecution witnesses. During the cross-examination, Grace changed her story and admitted that in fact she had been coached to give the story she had given by a Catholic priest who was secretly in the area.

It was then alleged that the Catholic priest had concocted this scheme as part of efforts to punish people for attending an Anglican church.

All three women were found not guilty.

Modern scholars believe the trial may have been part of a stratagem to ‘smoke out’ hidden Catholics in the area and that it had been concocted as a way of generating public outrage and justifying more intense government surveillance of the area.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend