The country is getting really gatvol and showing signs of losing hope.

A recent survey conducted by the Social Research Foundation (SRF) shows that South Africans see the country moving in the wrong direction. And another recent survey by the SRF shows that the majority of South Africans expect conditions to be worse after ten years.

The results of the surveys imply immense dissatisfaction with the ruling ANC, but also with rising prices and high unemployment, as well as the absence of improvement in people’s lives. There is also the feeling of hopelessness as people do not see things improving in ten years. This means that many are full of fear.

This sense of angst about where we are headed and the feeling of hopelessness raise the chances of outbursts of public violence. Dissatisfaction and loss of hope are often associated with a shift in support to radical solutions put forward by the left or right.

What are the political implications of these survey results showing dissatisfaction and loss of hope?

Both SRF surveys were conducted over the phone in July this year on a sample of 3 204 randomly selected and demographically and regionally representative registered voters. The surveys have a margin of error of 1.7 percent. The SRF is a recently established research body of which Frans Cronje, former Institute of Race Relations CEO, is a director.

Wrong direction

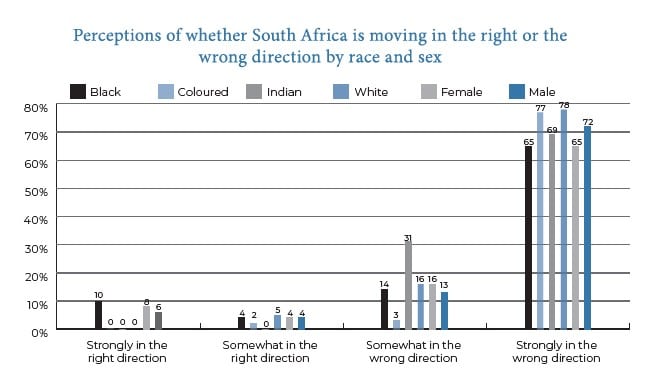

The weight of opinion in one survey is that South Africa is going strongly in the wrong direction, although there are important variations in beliefs. Regardless of race, age, income level, educational level, or political allegiance, people think things are getting worse.

Source: Social Research Foundation, Public Opinion on whether South Africa is moving in the right or wrong direction, August 2022 – Report 4/2022

People living in rural areas are slightly more positive than urban dwellers about the country’s direction. And ANC voters are more positive than opposition supporters. University graduates are less positive than those without a tertiary education.

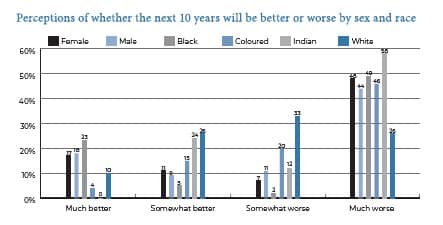

In the survey on whether the next ten years will be better or worse, more than half of registered voters expect a deterioration in conditions in the country over the next decade. About 17 percent are undecided on the issue, and roughly a quarter are optimistic about the country’s future.

Source: South Africans and their expectations of the next 10 years, Social Research Foundation, August 2022 – Report 5/2022

Worsening economic conditions will feed into the angst about the future. Slower growth, higher inflation, and continuing high unemployment, all of which are on the horizon, must raise levels of frustration.

We are facing strengthening headwinds from a slowing global economy and tightening US monetary policy. The recent commodity price boom which boosted tax revenue for the Treasury and helped our balance of payments is over for the moment.

Unemployment figures released last week came out slightly below the previous quarterly reading, but at nearly 34 percent, and at just below 46 percent under the expanded definition, are extraordinarily high by international standards.

South Africa’s latest inflation reading, released last week, was at 7.8 percent year on year for July, a 13-year high. The main drivers included food, housing and utilities, and transport – all prices that heavily impact the poor. With the rise in fuel prices, transport costs rose by 25 percent year on year, making this a key pocket book issue.

This sort of environment makes it difficult to build a vision and instill hope, which are important for a cohesive and dynamic society. As the SRF remarks on the survey on how the next ten years are viewed, there has so far been no individual or institution that has created this vision. That, it says, leaves, ‘a significant gap in the country’s social and political market’. The SRF says there is something to be said about the role of ‘an aspirational vision to lead a successful society’.

Aspirational vision

A party or coalition dedicated to an aspirational vision, such as going through some pain to ultimately turn the economy around, could emerge. But the politics of fear and frustration are more likely to mean that voters may be in the mood for charismatic leaders and draconian solutions. They would certainly have a vision, but it would be one that is more about division and retribution.

If the politics of frustration and anger take over, there will be two big priority issues – the position of foreigners, and expropriation without compensation. Both can fulfil a demand for apparent instant solutions, and address the issues that those who have lost hope may feel are at the root of the country’s problems.

The state of mind of the electorate could indicate that many political parties will increasingly try to capitalize on the mood of the country by adopting more radical positions. These could well include a commitment to speeding up expropriation without compensation and a crackdown on foreigners in the country. Rather than a commitment to economic reform to boost growth, coming from an aspirational leader with a vision, the type of policies likely to find the greatest favour will be those promising immediate solutions.

The Economic Freedom Fighters have protested outside restaurants employing foreigners and asked for the names of employees. It is possible that the Limpopo Health MEC Phophi Ramathuba’s lecturing of a Zimbabwean patient in a hospital with the complaint that foreign nationals were draining South African resources was at least partially for campaign purposes. The ANC is signalling that they know and understand the frustration of the electorate on this issue.

And now Gayton McKenzie, who leads the Patriotic Alliance, is quoted by eNCA as saying that he would walk into hospitals if he led the country and, ‘unplug that gas that they (foreigners) are enjoying from South Africa and I would bring somebody from South Africa and I would connect them to the gas. If they must die they must die’.

Party on the rise

Another small party on the rise, ActionSA, has a tough stance on immigrants, but a moderate and free-market position on a range of other issues.

That tough talk could be to compete with Operation Dudula, the growing movement which aims at dealing with crime, unemployment and poor health services caused by an ‘influx of illegal immigrants’. There has to be an open question as to whether Operation Dudula will turn itself into a political party.

What happens when small single-issue parties demand as a condition of entering a national coalition that foreigners, illegal and legal, be expelled?

Parties with a common populist viewpoint may find common cause in forming coalitions on these issues, which has to raise the chance of an ANC/EFF coalition.

But above all, this feeling of frustration and hopelessness raises the political uncertainty about our future.

[Image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/80497449@N04/7378191388]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend