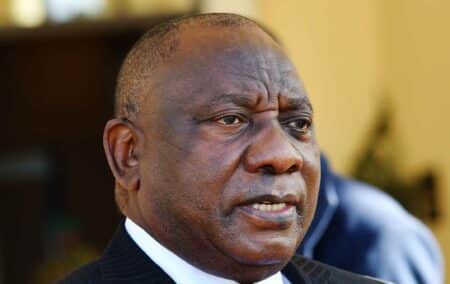

Last week, a Business Day editorial commended President Cyril Ramaphosa for the ‘important structural reforms’ being implemented under his watch.

These reforms, it said, included proposed private sector participation in rail and port infrastructure, increased scope for independent electricity generation, and the auctioning of high-demand spectrum.

The newspaper also commended the president for warding off the nationalisation of the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) and defeating ANC proposals for expropriation without compensation (EWC), which were ‘unlikely to see the light of day anytime soon’.

The editorial reflects the common wisdom regarding the president and helps to reinforce it too. Yet a wider overview reveals a different picture, for Mr Ramaphosa has in fact been remarkably successful in advancing the socialist-oriented national democratic revolution (NDR) to which the ANC has been committed for more than 50 years.

What follows is an incomplete list of the statutes, bills, and other policy decisions that have been put forward or endorsed by Mr Ramaphosa and his administration since he replaced Jacob Zuma as president in February 2018.

Relevant statutes include:

- the misleadingly named Protection of Investment Act of 2015, which was brought into force in 2018 and reneges on government promises to give fresh foreign direct investment from mainly Western countries the same safeguards against expropriation as (now terminated) bilateral investment treaties with those countries had earlier provided.

- the National Minimum Wage Act of 2018, which sets South Africa’s minimum wage at a high level compared to other countries, thereby further pricing the unskilled out of the labour market and exacerbating youth unemployment.

- the Competition Amendment Act of 2018, which expands ‘public interest’ conditions for merger approvals and empowers the competition authorities to order dominant firms in highly concentrated sectors to ‘divest’ themselves of some of their assets – not because they have abused their dominance, but simply because of their size.

- the Private Security Industry Regulation Amendment (Psira) Act of 2014, which the president signed into law in 2021 and which requires foreign private security firms to surrender majority control under a 51% local ownership requirement.

- the National Credit Amendment Act of 2019 (now to be redrafted), which allows the debts of over-indebted consumers to be ‘extinguished’ in various circumstances and could encourage a culture of non-payment and drive up the costs of credit.

Relevant bills include:

- the Expropriation Bill of 2020, which will allow ‘nil’ compensation on the expropriation of land in wide-ranging circumstances. By defining ‘expropriation’ in an unusually narrow way, this Bill will also allow the state to take custodianship of large amounts of land without this counting as an expropriation or meriting the payment of any compensation.

- the Land Court Bill of 2021, which will oust the jurisdiction of the ordinary courts over land disputes, including those over expropriation and custodial takings. The new court will jettison established evidentiary and procedural rules and often allow questions of fact to be decided by lay assessors likely to have partisan perspectives.

- the Employment Equity (EE) Amendment Bill of 2020, which will allow the state to set binding racial targets for senior management and other posts in all private companies with 50 employees or more. Since almost half of black South Africans are unemployed, under-educated, and under the age of 25, EE targets based on the overall black share of the working-age population (80%) are sure to be unrealistic and damaging – as is already the case in the public service, Eskom, and other state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

- the Public Procurement Bill of 2020, which will repeal the Preferential Procurement Policy Framework Act (PPPFA) of 2000 and its express limits on BEE preferences in procurement (a 10% price mark-up on state tenders worth R50m or more, and a 20% mark-up on smaller ones). Instead, this Bill will introduce set-asides for an escalating number of groups, including women, youth, domestic manufacturers, and township entrepreneurs, some of whom could follow the example of the ‘construction mafia’ in using extortion to secure their procurement ‘rights’.

- the Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Bill of 2021, which will compel the state, the private sector, and many other entities to achieve ‘equality…of outcomes’ on a host of different grounds, including race, gender, and (probably) socio-economic status or poverty too.

- the National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill of 2019, which will give the government comprehensive control over private healthcare, generate a single, state-run medical aid for the entire country (the NHI Fund), and establish a state monopoly over healthcare which is unlikely to be any more successful than its monopoly over electricity.

- the Climate Change Bill of 2022, which will set carbon budgets for SOEs and many businesses, lead to higher carbon taxes and other penalties for those who exceed their carbon allocations, and promote dependence on intermittent renewables incapable of meeting the country’s need for reliable and affordable electricity.

- the Electoral Amendment Bill of 2022, which will allow independent candidates to stand for election to the National Assembly but will do so on terms that advantage the ANC and could allow it, for example, to win 51% of the seats in the National Assembly with only 45% of the national vote.

- the Prevention and Combating of Hate Crimes and Hate Speech Bill of 2018, which will perversely often make it harder to punish people for the prejudiced motives behind their crimes. It will also allow people to be jailed for up to three years under overly broad prohibitions on speech that are likely to be selectively applied.

Relevant policy decisions include:

- a refusal to privatise Eskom or even to exempt it from the EE, BEE, and localisation rules that have helped cripple its generating capacity;

- a continuing commitment to cadre deployment, which is clearly unconstitutional (as the Zondo commission has confirmed) but helps give the ANC control over all ‘levers of power’, ranging from the public service and the police to the judiciary, the private sector, and the media;

- a refusal to allow parliamentary oversight or approval for the often unreasonable and irrational decisions implemented during one of the longest and harshest Covid-19 lockdowns in the world;

- an increasing reliance on public employment schemes, rather than labour market reforms, to counter the unemployment crisis;

- the introduction, in place of growth-stimulating reforms, of a social relief of distress (SRD) grant, which brought the proportion of South Africans receiving monthly cash grants from the state to close on 50% and which the fiscus cannot afford;

- the pending replacement of the SRD grant with a permanent grant for the unemployed which will be even more unaffordable and will be politically impossible to roll back even as it pushes public debt (already at some 70% of GDP) still higher;

- a long-standing determination to introduce a National Social Security Fund (NSSF) incorporating a mandatory state pension, mandatory state death and disability benefits, and a universal basic income grant. The NSSF will hobble the retirement and life insurance industries, thereby helping to ‘roll back the capitalist market’ (as the SACP puts it) and give the state control over social security;

- a refusal to take effective steps to boost growth and reduce public spending, which in time will put great pressure on the SARB to loosen monetary policy by printing money and reducing interest rates, even as inflation rockets. In this situation, there will be no need to nationalise the SARB as its core mandate and independence will have been eroded in other ways.

The common denominator underpinning all these acts, bills, and policy decisions (and many more besides) is the ANC’s commitment to the NDR, which the SACP has long identified as providing the quickest route to a socialist and then communist South Africa.

Mr Ramaphosa has recently become more open in his endorsement of the NDR. In July 2022, for instance, he told the SACP’s 15th national congress that the ANC was determined to ‘defeat each and every effort to derail the NDR’, which was the ‘shared programme’ of the ANC and the SACP and ‘the reason for the existence of our alliance’.

Later that month, the president told the ANC’s 6th policy conference that the gathering’s ‘central defining task…was to lay the basis for the restoration of the ANC and the NDR’ and to ‘emerge with policy proposals to put the NDR back on track’ in the wake of Zupta-linked state capture and pervasive maladministration.

Mr Ramaphosa is nevertheless usually depicted as a pragmatist held back from implementing business-friendly reforms by the ‘radical economic transformation’ or ‘RET’ faction within the ANC. Yet in his speech to the ANC’s 6th policy conference, the president himself made it plain that the divisions within the ruling party are ‘not divisions about policy or ideology’. Instead, they are ‘driven by the competition for positions…and the pursuit of access to public resources’.

In driving the NDR forward via the measures earlier outlined, Mr Ramaphosa is of course relying on the incremental steps the ruling party and its communist allies have been taking in many spheres for almost 30 years. The president’s business-friendly image has nevertheless allowed him to push ahead with vital NDR interventions with little critical scrutiny or overt opposition – making him arguably the most effective ‘RET’ leader of all.

[Image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/governmentza/52192457233]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend