Paul Ehrlich’s doom-laden book, The Population Bomb, informed opinions and public policy for decades. Not only was he wrong, but the real crisis now emerging is one of underpopulation.

When the facts change, it is wise to change one’s mind. Such nimbleness of thought, often attributed to the economist John Maynard Keynes (who was, to be fair, often wrong), appears to be beyond the capabilities of the 90-year-old Bing Professor Emeritus of Population Studies of the Department of Biology of Stanford University and President of Stanford’s Center for Conservation Biology, Paul Ehrlich.

In 1968, his book, The Population Bomb, popularised the supposed crisis of overpopulation. It was essentially a Malthusian theory, which argued that as population grew exponentially, the growth of resources would not keep pace. Consequently, Ehrlich predicted mass starvation in the 1970s and 1980s.

Ehrlich wasn’t the first to get wildly hysterical about population growth. A 1960 article in the respected journal Science declared that Friday 13 November 2026 would be ‘Doomsday’, as it would be on this date that the human population would approach infinity if its growth was not tempered.

Ehrlich advocated ‘various forms of coercion’ should people not prove willing to reduce population growth voluntarily. Scientists like John Holdren, and left-wing environmental lobby groups like the Club of Rome, took up this message, and advocated various coercive measures, up to and including forced sterilisation, to limit population growth.

The United Nations (UN) launched a series of population conferences aimed at addressing the ‘population crisis’. It has moderated and qualified its rhetoric since the turn of the century, but to this day it frets about ‘decoupling the growth in population and in economic activity from a further acceleration of resource extraction, waste generation and environmental damage’.

Lobby groups agitated for zero population growth, or even a dramatic population reduction to below one billion people, for fear that overpopulation would result in rising poverty and running out of resources. They just loved China’s cruel and despotic one-child policy.

All their apocalyptic predictions have come to naught, although Ehrlich maintains that he was substantially correct, and continues to warn of the collapse of civilisation as a result of overpopulation, overconsumption by the rich and poor choices of technologies.

Last year, I called these people the new eugenicists.

Reality fails to conform

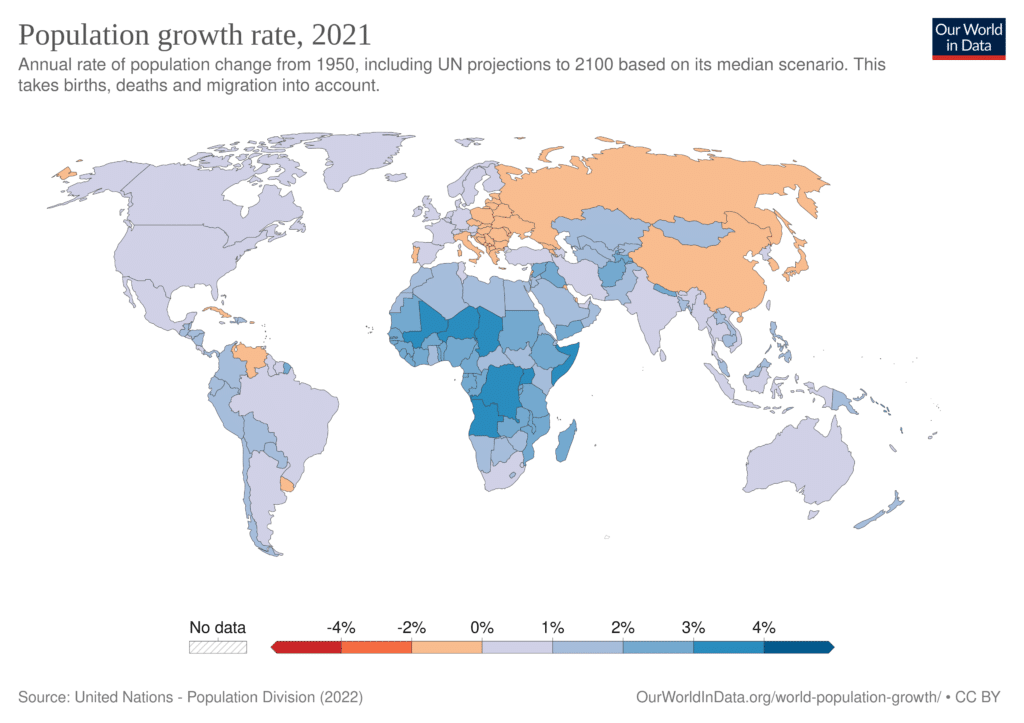

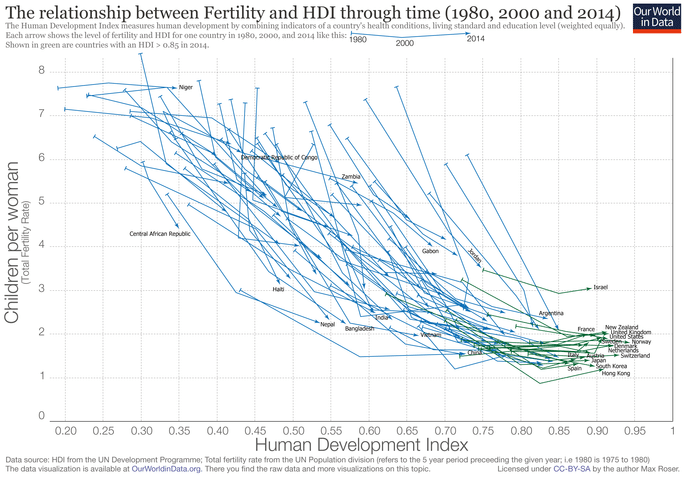

All these apocalyptic warnings came during an era in which population growth was already on a steep downward trajectory:

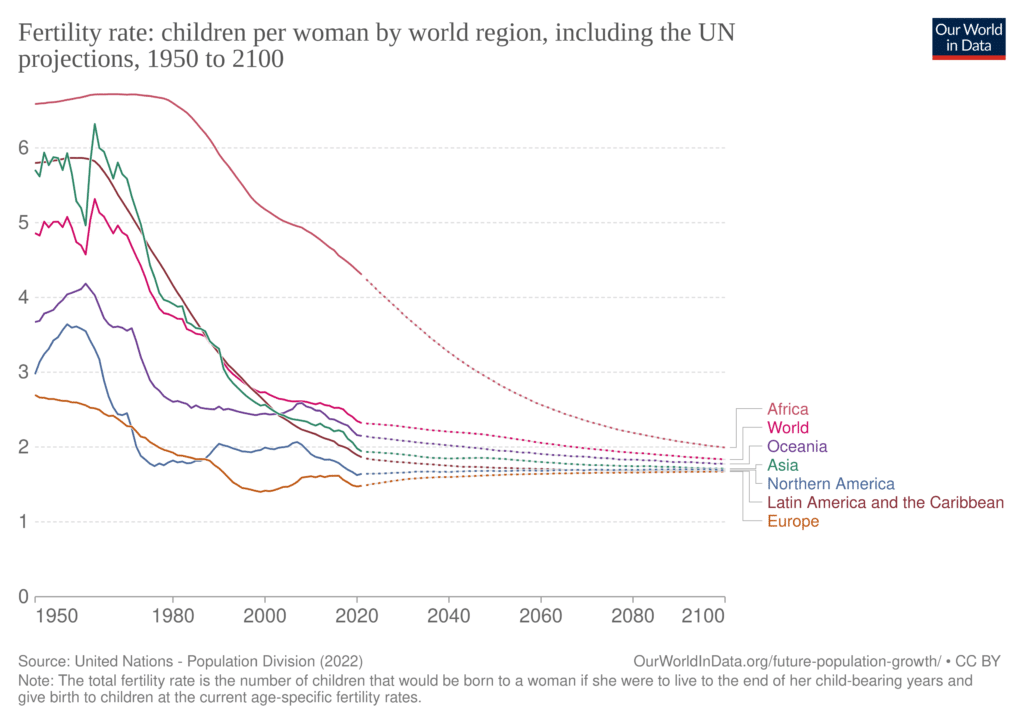

Between 1900 and 2000, global population grew from 1,6 billion to 6,1 billion, a rise of 281%. Between 2000 and 2100, population is expected to grow from 6,1 billion to 10,9 billion, using the UN’s medium projection. That’s only a 79% increase. By then, the global population growth rate is expected to be almost zero.

And this is only the medium projection. With lower fertility and higher death rate assumptions, the UN population projections for 2100 go as low as 8,8 billion. Other models are even more pessimistic, showing accelerated population declines after 2050.

Reality has failed to conform to the apocalyptic population explosion theories of the 20th century.

Even the UN has recently recognised that population growth is now limited to poor parts of the world. ‘At the global level, population decline is driven by low and falling fertility levels. In 2019, more than 40 per cent of the world population lived in countries that were at or below the replacement rate of 2,1 children per woman; in 2021, this share climbed to 60 per cent.’

By region, only Africa and Oceania’s fertility rates remains above the population replacement rate of 2,1 children per woman, although the latter is at a mere 2,14 and declining. All other world regions have fewer children than are necessary to sustain their present population levels.

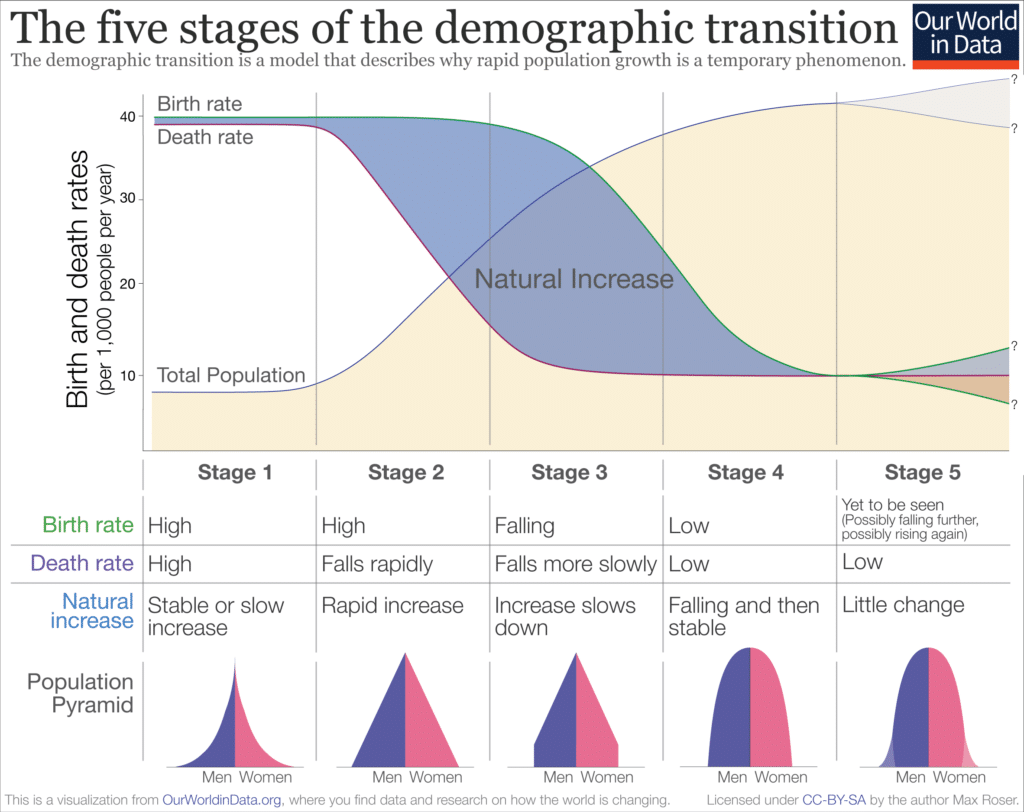

Perhaps the biggest insight of the discipline of demographics is the idea that rapid population growth is a temporary phase. What happens is that as societies become more advanced and prosperous, the death rate begins to fall, and the population begins to grow rapidly.

After some time, structural changes in the economy, including improved education for women, female participation in the workforce, declining childhood mortality, and the rise of family planning, cause birth rates to fall, too.

This slows down the rate of population growth, until it plateaus and begins declining. This process is called the ‘demographic transition’.

Underpopulation

Declining populations are a problem.

Some believers in the old Malthusian model argue that population decline will improve living standards, since fewer people compete for the same resources.

It isn’t that simple, however. Resources don’t simply exist as a pile of wealth that can be distributed among whatever population exists in a region. We’re not animals, or hunter-gatherers, anymore.

Prosperity is a function of production. Production requires several factors, one of which is labour. People who do not work, do not generate prosperity. The fewer people who work, the less wealth can be created.

With low death rates and low birth rates, the age profile of the population keeps rising, until there are not enough young, working people to pay for the pensions of the old.

China’s one-child policy, which was progressively lifted between 2015 and 2021, has given rise to alarm about its declining fertility. The UN estimates that its population will begin to shrink as early as next year, and likely halve by 2100.

This would have tremendous consequences for China’s own economy, with global repercussions. As it spends more and more of its GDP on supporting the elderly, and the ranks of the working-age populations thin, China’s great economic expansion will come to a grinding halt, as will its ability to project power.

In a dramatic turnaround, China is now desperately encouraging people to have more children.

The same underpopulation problem occurs in other world regions. Immigration can plug the gap for a while, keeping economies afloat, tax coffers filled, and social welfare schemes funded. Eventually, however, the only way to avoid a demographic and economic crisis is to raise birth rates, somehow.

Misanthropic

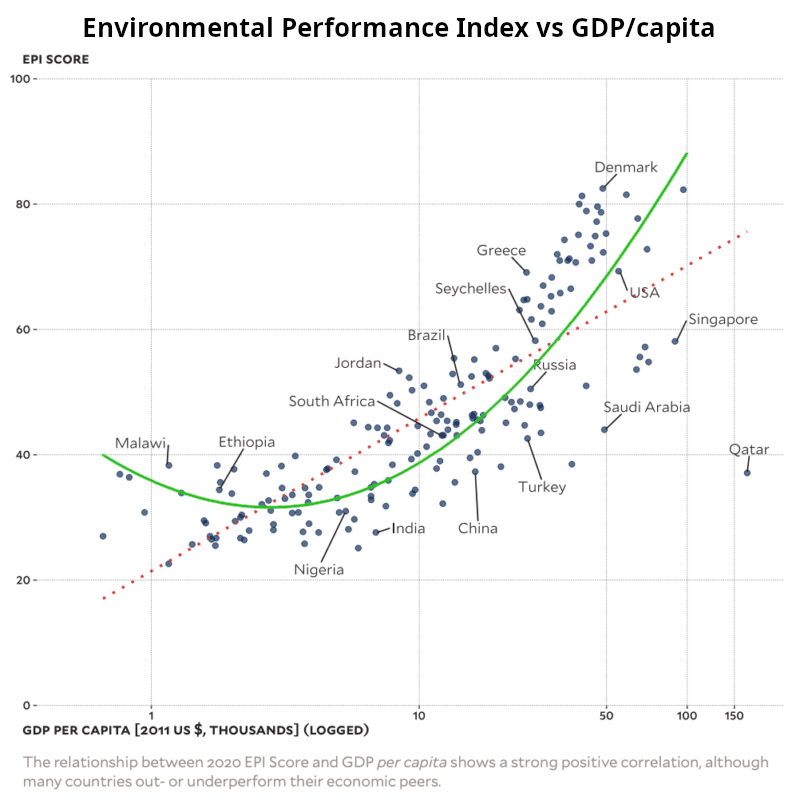

Environmentalists will tell you that humans are a scourge on the face of the planet, and the fewer of us there are, the better it will be for the environment. This is not only a misanthropic view, but as a correlation, it is not true.

As soon as countries begin to become more prosperous, they learn to marshal their resources better and take better care of the environment. The world’s environmental challenges are not a function of population size, but a matter of insufficient prosperity and poor environmental management.

In the developed world, there was far more pollution going on 50 years ago, when populations were smaller, than there is today.

Declining populations will likely make environmental problems worse. Fewer people, with fewer good ideas and less productivity, will ultimately result in de-industrialisation and a return to privation and poverty. That is worse for the environment than abundance and prosperity.

We may be the first generation able to solve the world’s environmental problems, but if we do not sustain our prosperity, we may also be the last.

Consequences

It isn’t yet clear how far-reaching the consequences of underpopulation will be.

We can confidently predict that declining populations will make elderly care more difficult, both because there will be less production to pay for their upkeep, and fewer people available to care for them.

It will reduce military strength, since the population will skew too old. It will reduce innovation, since innovation comes from the young. It will also cause long-term decreases in both GDP and tax revenue, with all the consequences those entail.

Traditionally, large and growing populations have been associated with successful societies, while small and shrinking populations are indicators of societies in decline. Despite the fashionable overpopulation fears of the last half-century, this remains true.

The consequences of false narrative of overpopulation are myriad. It promotes feelings of guilt, both for simply existing, and for bringing children into the world. It reduces concern for disasters, wars, diseases and other factors that kill people. It makes people hostile to those who have more than they do, and indifferent to the suffering of people far away.

It convinces people, especially among the elites, to support destructive ideas such as ‘degrowth’, which will reverse the last half-century’s dramatic progress in poverty reduction and improved standards of living.

Good news

The good news is that the correlation between a country’s level of development and its fertility rate is not always negative. As countries become prosperous, fertility does decline, but there is emerging evidence that suggests at very high levels of development, fertility begins to rise again.

It is too early to assign causes to this phenomenon, but one can speculate that increased wealth and leisure time might make parents more willing to have larger families. Whatever the causes, it does give some hope that the underpopulation crisis need not be permanent.

Still clinging to the idea that overpopulation is a threat to either civilisation or the planet will prolong the real crisis of population decline. We cannot afford to still think like the false prophets of doom of the 20th century.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend