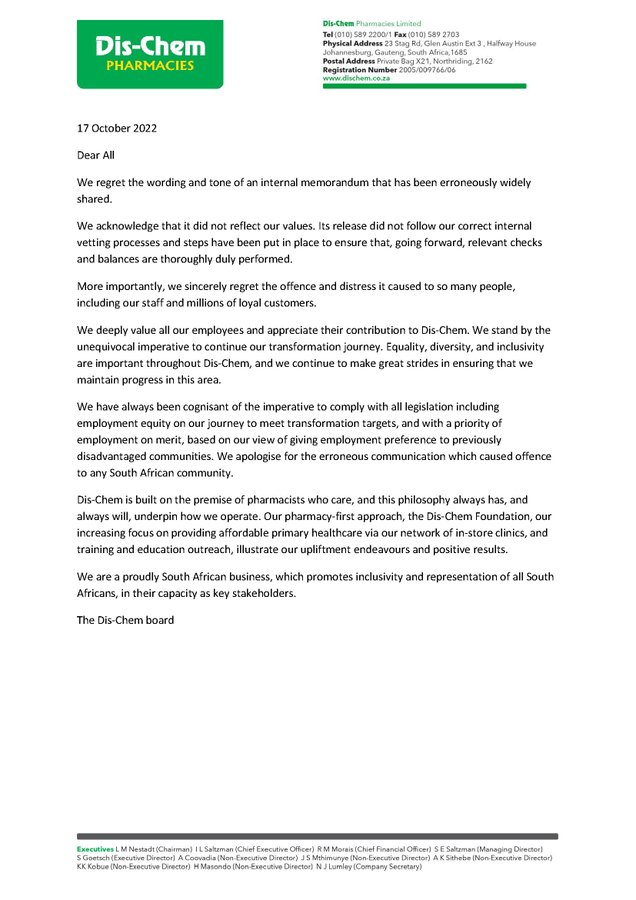

It remains unclear whether Dis-Chem has withdrawn its moratorium on the hiring of white people. A letter to the public earlier this week on the matter said the order to its staff that decreed a moratorium was not in line with the company’s values. But there was no explicit statement that it would now lift the moratorium. *

Whites make up about 30 percent of the firm’s customer base, and given the level of anger, the impact of a threatened boycott on social media on the pharmacy chain’s turnover could still be serious.

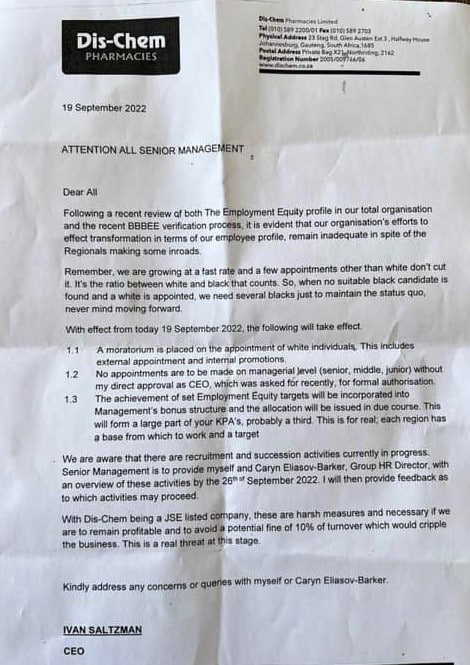

The tone of the letter to senior managers from Ivan Saltzman, the CEO of Dis-Chem, which decreed a moratorium reads as if he is in a panic.

The episode might well find its way into a book of case studies on reputational damage. It also might teach some of South Africa’s biggest corporations a few lessons on how to better navigate the treacherous waters of employment equity. And it might also teach them the need for backbone to stand up for themselves against government regulation.

The stew in which Dis-Chem found itself was probably the outcome of its fear of what will happen when the President signs the Employment Equity Amendment Bill, which was passed by Parliament earlier this year. The government is toughening up on enforcing affirmative action. When passed, the Labour Minister will have discretion in setting racial targets for different industries.

The firm’s board might have feared a fine of up to ten percent of turnover would be imposed once the new law was in place. If the company had incurred this on its R30.4 billion turnover last financial year, the fine would have amounted to R3.04 billion, and more than wiped out its operating profit.

Challenge

But Dis-Chem did not show it understood that even under the new legislation it would have been able to challenge the fine on the basis of context and its hiring challenges, and its current employment practices and problems.

There are two key Constitutional Court cases to guide practice on employment equity, but that does not make things easy. Both court decisions allow a degree of flexibility, but have also sown a degree of confusion. Bato Star Fishing vs the Minister of Environmental Affairs came before the Court in 2004. Justice Kate O’Regan held that in the allocation of fishing rights there was no one-size-fits-all approach to transformation and the decision should depend on the circumstances of the case.

In SA Police Services vs Barnard, heard in 2014, the court found that a white woman who wanted a promotion was legitimately turned down, as the measures in place were temporary and not permanent. The then Acting Chief Justice Dikgang Moseneke upheld the view that affirmative action has a transformative mission aimed at achieving substantive equality for those previously disadvantaged by past unfair discrimination. However, measures aimed at remedying past discrimination must be carefully formulated to avoid invading the dignity of those affected.

If it had been taken to court, Dis-Chem would have had to prove that its moratorium on white hiring was temporary. But this could have been viewed as pure discrimination as it is equivalent to a quota. Under employment equity law racial quotas are illegal, but targets are legal. But that raises the question about whether to achieve a target, quotas are required.

Employment equity is a nightmare. Targets move with demographic changes and staff turnover and as the needs of companies change. And then there are varying racial demographics at regional and local levels, which may or may not apply. The selling off of stakes by empowerment partners can require a new round of deals. Companies might have to lay-off or take on new staff at different skill levels due to new technology or mergers or acquisitions, and that could change the racial composition of the workforce.

Local investors have no option but to grin and bear the system. But overseas investors don’t like it at all because it is shifting and expensive to implement. That is just one reason they tend to stay out of the country.

Over the past few years Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) listed companies have been faced with increasingly onerous reporting obligations on their racial transformation status. One lawyer familiar with the process says despite efforts at clarifications by the B-BBEE Commission, a trade and industry department body, there are still uncertainties on some aspects of reporting.

Listed companies are required to provide information on, for example, the percentage of black shareholders, their gender, age, location, and whether they are disabled, and much more. Having to source this information imposes a heavy burden on companies. This is just one reason why an increasing number of companies no longer think it is worthwhile to continue with a listing. It is a reason why the number of JSE-listed companies is a small fraction of what it was just 20 years ago.

Racial breakdown

Dis-Chem’s panic might have been sparked by the fear that the racial breakdown of its staff and board are out of line with South Africa’s demographics. In its last financial year, Dis-Chem employed 20 000 of whom, 69.3 percent were black Africans versus 81 percent in the national population and 15.5 percent, were white versus 7.7 percent in the national population. Achieving its racial goals might not be helped by its high staff turnover rate of 23 percent.

The firm’s overall broad-based black economic empowerment score is low, even with a recent empowerment deal. The Saltzman family, who founded Dis-Chem, sold just over 10 percent of its shareholding to an empowerment group last year. That upped the empowerment stake in the company and helped push the company’s overall B-BBEE score from non-compliant to Level 8, the lowest rung on the B-BEE level. Its rival, Clicks, has a rating of Level 4, which is a far better score.

In an already over-regulated economy, empowerment is a disincentive for investors. It is expensive and burdensome to be compliant, in large part due to the reporting and verification requirements. The government cannot simply accept that firms want to transform because they want to grow and have more skilled employees. It is in their interests.

Having at least to approach or meet racial hiring targets against a rapidly changing economic and demographic landscape is a nightmare. It is akin to central planning of hiring. Most corporations have to try and get the best person they can at the time. Doing things on a racial basis is bad for business and bad for the economy.

The alternatives to empowerment laws that could really work in ensuring a more just country are far faster economic growth and greatly improved and more wide-scale education and training.

Extremely wary

Dis-Chem and much of corporate South Africa are extremely wary of taking a wrong step on transformation. As much as they speak about government failures on Eskom and Transnet, this is one area in which they will hold their silence.

What Saltzman and others might instead do, is get some backbone and lobby the government on the entire issue of employment equity and empowerment. But, realistically, this is not about to happen. They would be labelled as anti-transformation or even worse.

* The author has amended this paragraph to acknowledge the uncertainty about Dis-Chem’s position.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend