A society dedicated to institutions – as opposed to personalities and factions – is one that seeks stability and predictability around its supreme constitution.

Even if its written constitution is not particularly good, it can benefit from gradually reimagining the text (within the reasonable elasticity of language and the normative tradition of constitutionalism) instead of changing or replacing it outright.

The South African Constitution allows a lot of reimagining, particularly because it has hitherto been misconstrued by the courts and particularly by the legal community. Constitutionalism is necessarily liberal and seeks to place limits on government power. But the legal community, and on occasion the courts, have approached the South African Constitution in an authoritarian fashion, construing it as something that expands government power at the expense of liberty.

They have attributed meanings to the Constitution that the text cannot reasonably sustain, in a way that is contrary to the purpose of a written constitution.

Reimagining South Africa’s Constitution is therefore quite simple: replace misconstructions with proper, constitutional(ist) constructions. The text of the Constitution is that of a good, liberal constitution.

Although that works for most of the Constitution, some of its imperfections cannot be cured through reimagining alone, as doing so would stretch the text beyond what the ordinary meaning of the language can bear. Other imperfections might be cured through reimagining but could still benefit from clearer constitutional language.

In this article, I suggest some textual changes to the Constitution (in no particular order) that would benefit society and also render the Constitution a stronger version of itself.

Remove any vestiges of racialism

Despite being fundamentally committed to non-racialism in section 1(b), the Constitution nonetheless contains a tiny handful of racial provisions that should be removed.

Section 174(2) of the Constitution provides that when judicial officers are appointed, the ostensible need to ‘reflect broadly the racial and gender composition of South Africa must be considered’.

Section 193(2) provides the same for when members of Chapter 9 commissions are appointed.

Section 195(1)(i) of the Constitution provides that the public administration in general ‘must be broadly representative of the South African people’. This provision has been interpreted racially, but in light of section 1(b) it can and should be actively interpreted as not referring to race or sex. Nonetheless, it does leave room for abuse.

It may come as a surprise to South Africa’s professional race-hustlers, but that is it. That’s the extent of the constitutional provision for racial discrimination, and it is limited to appointments in government and the judiciary. There is no constitutional provision for private enterprises having to reflect the national demographic composition. Nonetheless, these extant provisions should be significantly amended or removed.

Get rid of the JSC

The creation of the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) was a mistake. It guaranteed that, as South African politics alternately moderated and radicalised, so too would its judges. Giving politicians, in proportion to their party’s share of the seats in the National Assembly, a determinative say in the composition of the judicial branch of government ensures that political (as opposed to judicial or legal) considerations play a key role in what is supposed to be an impartial institution.

There are other safeguards built-in, to be sure. Judges cannot be plucked from the street. At the very least, they must be people with some experience in either teaching or practising law. But even with these safeguards – and despite the fact that today, our judges arguably remain the best on the continent – the current system of judicial appointments leaves a lot to be desired. The JSC makes a mockery of the judiciary and undermines the independence and majesty that is crucial to its proper functioning.

The JSC ought to be replaced with a system whereby the senior counsel of South Africa choose our judges, from magistrates all the way to the justices of the Constitutional Court.

Senior counsel are our most experienced advocates, who have usually spent decades appearing in South Africa’s courts. They know better than most – certainly better than the politicians currently stinking up the JSC – what the qualities of a good judge and those of a bad judge are. They do not – for the most part – care about the irrelevant political nonsense the JSC tends to burden candidates with.

When there is a vacancy for a magistrate, all the senior counsel who permanently reside in that district must form an electoral college. The public and legal fraternity can nominate candidates and send those nominations to the college, which must then elect the new magistrate. Alternatively, they can form a shortlist from which the Minister of Justice must appoint the new magistrate.

The same applies to the high courts. The senior counsel of a province where there is a vacancy must elect a new judge or send a shortlist to the President. In the case of the Supreme Court of Appeal, the Constitutional Court, and other national courts, all the senior counsel in South Africa will form one large electoral college to choose judges. For the Constitutional Court, votes might even be weighted by the seniority of the electors.

The whole process can be administered by the independent bar councils – certainly not a state institution like the Legal Practice Council. A further safeguard might be to make elevation to senior counsel automatic after an advocate has practised for 15 years cumulatively, rather than leaving it to the President to appoint them at his discretion.

Bad apples, as always, can be disbarred, and a mechanism could be established by which existing senior counsel might prevent a specific colleague from attaining silk.

Bring federalism to the fore

The Constitution is a federal constitution. This is borne out by the fact that provinces and (particularly) municipalities have original constitutional powers that do not depend on the generosity of the central government. Furthermore, the provinces have representation in the National Council of Provinces, meaning they participate in central governance. These are both hallmarks of federation.

South Africa is nonetheless a centralised federation that lacks any hint of a federalist political culture amongst the holders of power.

Probably the best way to make federalism a practical reality is to either 1) internally subdivide the South African Revenue Service into provincial branches which will come under the control of provincial treasuries, or 2) allow every province to establish its own revenue authority. Each option has its pros and cons.

The first option will ensure there remains a single tax structure in South Africa, bringing about certainty and, likely, significantly lower tax rates than the alternative. Money will flow up from the provinces to the central government, rather than down to the provinces from the central government, as is currently the case.

The second option will make the provinces and central government financially independent of one another, without any financial flows between them. This however might mean double taxation, as provinces levy their own income and sales taxes in addition to what is payable already to the central government.

Similar provisions should also be adopted for provinces as already exist for municipalities: empower provinces to exercise any power that is necessary or incidental to the effective performance of any provincial function. Significant swathes of law enforcement and economic policymaking should also be expressly vested in provinces and municipalities.

No more state businesses

Three decades of experience is a difficult record to ignore: Government and business, in South Africa at least, do not mix well. A general constitutional prohibition on government-run enterprises would be a welcome change.

There are only two mentions in the entire Constitution to ‘public enterprises’ – surprising in light of how huge a (detrimental) role they play in the economy. The first is in section 195(2)(c), which applies the values of the public administration to state-owned enterprises, and the second is in Schedule 4, referring to ‘provincial public enterprises.’

Both references should be removed. They should be replaced with a provision somewhere in section 195 prohibiting any organ of state and sphere of government from establishing an enterprise, purchasing an enterprise, taking over (through expropriation or nationalisation) an enterprise, or managing or administering an enterprise.

This could be combined with another provision that provides explicitly that all goods and services must be supplied by privately-owned enterprises, although the state may purchase these on behalf of consumers and end-users where necessary. This would make everything currently housed in state-owned enterprises part of the ordinary system of public procurement.

Reorganise the Bill of Rights

Some things in the Bill of Rights are rights, and some things are not.

It is incorrect to say that the only rights are individual (‘human’) rights – those rights people have by virtue of their existence – as many other (‘personal’) rights are established through contract. What is correct is that rights cannot be ‘created’ out of nothing. A contractual right has a clear underlying cause based on the will of the parties to the contract. Individual rights are born out of the very nature of reality and humanity: we are born as individuals with our own consciences and bodies, with the result that we as individuals must determine our own affairs.

But a ‘right to health’ or a ‘right to housing’ is not based on any underlying cause or the nature of reality. The underlying reality is that one’s health and housing have throughout human history been rightly regarded as the responsibility of the person, their family, and their community. These created ‘entitlements’ are not correctly conceived of as rights, and should therefore be treated differently in the Constitution.

It would not be practical politics at this stage to ask for their removal from the Constitution, however ideal that might be. But there must be a reconsideration in how they are approached.

These ‘rights,’ then, can become directive principles of State policy. That is to say: government must, within its available means – after it has financed and provided the core services of government: public debt, policing, defence, and the administration of justice – work toward the progressive realisation of these principles. Nobody can go to court to claim these principles directly, but they will form an integral part of government’s budgeting process.

No less a jurisprudential antagonist than Dennis Davis – whose work advances social engineering at the expense of constitutionalism – favoured the directive principles approach, when he wrote in 1992:

‘Where a bill of rights strives to do more, it can destroy autonomy and removes politics to the court room. To overemphasize the importance of rights by introducing a battery of specific social and economic demands in a constitution is to place far too much power in the hands of the judiciary, which however appointed or elected is never as accountable to the population as is the legislature or an executive.’

The Bill of Rights as it stands, in other words, should be divided into a Bill of Rights (comprising sections 7, 8, parts of section 9, sections 10-22, parts of section 25, parts of section 28 and 29, and sections 30-37) and the Directive Principles of State Policy (comprising the other parts of section 9, sections 23, 24, the other parts of section 25, sections 26, 27, the other parts of section 28 and 29).

Clarify the Bill of Rights

After the reorganisation, some clarity could also be brought to provisions of the Bill of Rights that three decades of experience have revealed are prone to misconstruction.

Section 9 – the right to equality – for example, has been errantly misconstrued as allowing government to engage in racial social engineering, when other provisions of the Constitution militate against such a reading. Section 9 should be tidied up and provide clearly that it is not an empowering provision for discriminatory government action. ‘Fair discrimination’ means a movie studio may tell a pudgy white actress that she is not suited to portray Nelson Mandela in its upcoming film. It does not mean government planners may decide who employers may and may not hire as employees.

Section 36, too, has been regarded by many as a one-stop shop to nullify the application of constitutional rights when they prove inconvenient to government. This is obviously not its purpose. The ‘limitations clause’ should be modified to show that it is intended to constrain government’s attempts to limit rights, not provide an avenue for government to do so.

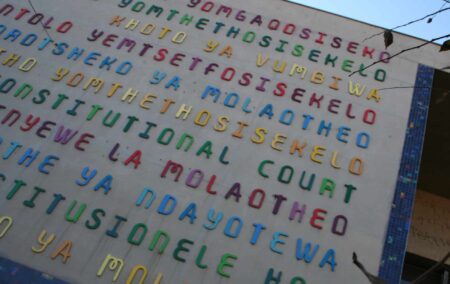

[Image: André-Pierre from Stellenbosch, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5608955]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend