The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species faces a crisis of legitimacy. It tramples the successful conservation models of range states at the behest of Western NGOs with a radical prohibitionist agenda.

Botswana and Zimbabwe have proposed an amendment to Rule 26 of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) at the 19th Conference of the Parties (CoP) in Panama City, presently underway.

In it, they argue that when making decisions about changes to Appendices I and II, which specify species in which international trade is to be restricted or prohibited, the number of votes assigned to member states shall be proportionate to the population size of the relevant species under that state’s jurisdiction.

Since 1975, CITES has imposed global trade prohibitions or restrictions intended to protect species threatened with extinction. It has largely failed.

It has also lost the support of many range states, who view CITES (and the international non-governmental organisations that egg it on) as neo-colonialists who disrespect their views and violate their sovereignty.

CoP19 should very seriously reflect on the Rule 26 proposal, and on Tanzania’s closing statement at the 18th CoP on behalf of the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

In it, these 16 countries – home to many iconic species such as elephant, rhino, lion and giraffe – threatened to withdraw from the treaty altogether.

Unjust voting

‘Today CITES discards proven, working conservation models in favour of ideologically driven anti-use and anti-trade models’, they lamented. ‘Such models are dictated by largely Western non-State actors who have no experience with, responsibility for, or ownership over wildlife resources.’

They argue that CITES operates in violation of its own charter, which recognises that ‘peoples and states are and should be the best protectors of their own wild fauna and flora’, as well as against the injunction of the Convention on Biological Diversity that states have ‘the sovereign right to exploit their own resources pursuant to their own environmental policies’.

Botswana and Zimbabwe, too, argue that CITES voting is unjust, since countries without significant populations of species are able to determine the voting outcomes on issues whose impacts do not affect them in any way, yet are burdensome on parties with significant populations.

‘The voting rules are currently not assisting in addressing conservation challenges and implications on affected parties, including local communities’, they write. ‘Countries whose ecosystems and human lives are suffering due overabundance of these species or animals should have a bigger voice in decision making and this should be reflected in having more votes. Countries which have healthy and sometimes overabundant populations beyond ecological carrying capacity of specific species listed under either Appendix I or II have been victims of the current voting procedures removing incentives to conserve such species.’

Abject failure

CITES’s success ought to be measured by whether a listing has indeed protected the species, whether it has stamped out not only legal trade, but also poaching and illicit trade, and whether its management strategy has improved the welfare of the people living with wild species.

By this standard, CITES has a history of abject failure. Wildlife population numbers declined precipitously despite CITES protection, its prohibitions have fueled illicit trade and made poaching more profitable, and the locals are outraged at high-handed dismissals of their legitimate interests.

It is little wonder, then, that range states, whose people have to live with the listed species, and often rely on them for a living, are rebelling.

Of the approximately 2210 proposals CITES has considered in its 37-year existence, 63% originate with just four countries: the United Kingdom, the United States of America, Switzerland and Australia. The organisation is dominated by the Global North, yet most of its decisions affect countries in the Global South.

CITES cannot expect to dictate to countries how their people are to co-exist with species that can be a rich resource, an opportunity cost, and a risk to human welfare. If it does, it must expect local people with local knowledge, traditions and management strategies to be alienated by such rudeness.

Steaming ahead

Comprehensive reform must be at the top of the CITES CoP19 agenda. It should give range states the power to veto its decisions, or at least weigh their votes far more heavily than those of countries who have no direct interest in the species under consideration.

Instead, it is steaming ahead, like the colonial empires of old, as if the resounding vote of no confidence issued by southern African countries at CoP18 was just a little awkwardness from uppity natives.

The CITES Secretariat has bluntly recommended that Cop19 not adopt the Rule 26 amendments proposed by Botswana and Zimbabwe, on the superficial grounds that it would conflict with the basis on which the United Nations operates.

‘The proposed system of voting shares is more used in corporate law and corporate governance where shareholders have a say depending on the number of shares they have’, it argues. ‘Given the level playing field established by the principle of “one country, one vote,” the proposed amendment to Rule 26 would contradict this principle.’

How the playing field is level when range states are routinely overruled by countries with no interest at all in the species under consideration, or why CITES ought to operate on the same voting basis as an international political organisation, they leave as an exercise for the reader.

Dismissive

Their dismissive response shows that developing countries have no voice, and range states will always be overruled by activists and politicians who play to the sentiments of rich-world elites and believe they know what’s best for poor countries.

It will come as no surprise, then, that for the third conference in a row, proposals by South Africa, Namibia, Botswana and Zimbabwe to resume limited trade in elephant ivory stocks by countries where populations are abundant have been rejected.

Instead, CoP19 is considering a proposal drafted by animal rights lobbyists but nominally advanced by Burkina Faso, Equatorial Guinea, Mali, and Senegal to move the elephant populations of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe – where elephants are thriving – from Appendix II to Appendix I.

The neo-colonialism of CITES has to end. Either it must take reform seriously, or range states will, with very good cause, walk away.

Conservation models

A comparison of the North American Conservation Model, based on government management of common wildlife resources, with the South African Conservation Model, heavily reliant on private property ownership, shows the latter is more effective.

The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation holds that wildlife is owned by no one and is held in trust by government for the benefit of present and future generations.

Established by the avid hunter and naturalist, president Theodore Roosevelt, it recognised all ‘outdoor resources’ as one integral whole, their ‘conservation through wise use’ as a public responsibility, and their private ownership as a public trust.

Their management is conducted by technocrats, employing science as a tool for discharging that responsibility, much like the Soviets thought about the management of economic resources.

Underscoring its elitist character, it rejected hunting for profit or for the pot, recognising only sport hunting as legitimate. It held that markets for wildlife and wildlife products are, with few exceptions, unacceptable because they privatise a common resource and lead to population declines.

CITES was founded on a broadly similar philosophy.

Common ownership

While American wildlife managers will tell you about the successes of the North American Model, they overlook the fact that many major species have continued to decline, while others, like white-tailed deer and coyotes, have grown into outright pests.

Its failures led to the rise of a parallel field of study, conservation biology, which calls itself a ‘crisis discipline’.

These managers also ignore that the Model relies on a complex bureaucratic planning regime that cannot be replicated in less developed countries.

Animal rights organisations, which oppose all productive use of wildlife as a matter of principle, seek to move even further towards common ownership of wildlife.

Yet the problems of overexploitation and extinction of wildlife have always derived consistently from their being treated as a common property resource.

The second way to resolve the tragedy of the commons is to establish private ownership of wildlife, in the same way that the tragedy of the commons in food production is averted by private property rights.

South Africa has followed this second route, turning a great deal of its wildlife management over to the private sector.

Private ownership

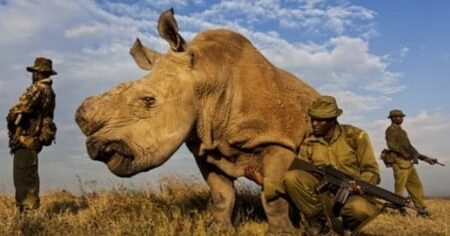

In the mid-20th century, the white rhino had been on the brink of extinction. After a successful breeding programme at the Hluhluwe-Umfolozi Game Reserve, its warden, Ian Player, launched Operation Rhino.

Player exported selected breeding groups to other game reserves, as well as to private game farms and zoos. This successfully re-established white rhino populations around the country.

This was followed by a major legislative change in 1991, establishing ownership rights in wild game which had hitherto been considered res nullius, or unownable.

The combination of secure private property rights and market pricing were all the incentive private game ranchers needed. It now made financial sense to breed rhino and hunt them selectively to fund operations.

White rhino numbers began to grow dramatically, from fewer than 6 000 in 1991 to a recent peak of 21 000.

Today, they are no longer considered endangered or threatened, although a prohibition on rhino horn trade and restrictions on transporting game trophies have created a new and dangerous black market in poached rhino products.

The population of black rhino offers an instructive comparison. Most black rhino were found outside South Africa’s borders, where they were largely owned and managed by governments, in the North American style.

While white rhino numbers were recovering, the black rhino population crashed from 100 000 in 1960 to just 2 300 in 1993, except in South Africa, where its small population increased.

Much of the recent recovery in the black rhino population, to about 5 500 animals, can be attributed to South Africa’s conservation model, also applied in Namibia, with its strong emphasis on private game ownership.

The private sector in South Africa now protects more rhinos than there are rhinos in the whole of the rest of Africa combined.

Game ranching

The success of private-sector conservation is not limited to rhino. In 1965, game was practically extinct outside National Parks. Today, there is more than three times as much wildlife on private land as there is on state-protected land.

Many game species, both large and small, have been saved from the brink of extinction and bred out of danger on private game ranches.

Conservationists often scoff at game ranching, arguing that it contributes little to true conservation. It is true that game ranches might not be as large, pristine or diverse as National Parks. However, they play a key role in keeping land under game – as opposed to livestock or crops – and increasing wildlife populations.

A study in 2014 by three American scholars, Daniel S. Licht, Brian C. Kenner, and Daniel E. Roddy, concluded that the South African Conservation Model outperformed the North American Conservation Model.

They found that it was more likely to reintroduce and conserve small, nonviable wildlife populations, reintroduce and conserve top-level predators, have more intensive management of wildlife, manage wildlife in partnership across multiple landowners, engage local communities, be self-funding, and restrict ecosystem damage due to excessive visitor movement.

They concluded: ‘The South African model is arguably more effective in conserving biodiversity as measured by conservation of apex predators and natural processes.’

In protecting species from decline and extinction, the ideological hostility to private game ranching, hunting and trade is counter-productive, despite what environmental and animal rights lobby groups would have CITES delegates and the wider public believe.

Giraffes

The successful listing on Appendix II of the entire Giraffa camelopardalis species ‘as a precautionary measure’ set a troubling precedent for the conservation of wildlife.

It punishes the successful conservation methods adopted in southern Africa for the decline in giraffe populations in east Africa.

At the time of the decision at CoP18, the single giraffe species was subdivided into nine subspecies, all of which have geographically distinct ranges. (Recent genetic research has suggested separating giraffes into four species with eight subspecies. That leaves both the IUCN Red List and CITES Appendix II outdated, so we refer here to the status quo as at CoP18 in 2019.)

Of these nine subspecies, only three are listed as endangered. A fourth is listed as near-threatened. All four have ranges in east Africa.

By contrast, populations of the southern giraffe, which ranges predominantly in South Africa, Botswana, Namibia and parts of Zimbabwe, have been increasing in abundance for over 30 years.

This is largely due to the success of the South African conservation model, which creates viable habitat not only in formal, state-owned reserves and protected areas, but also across a large and vibrant network of privately managed ranches, game farms and reserves.

These private ranches are largely funded by hunting and live animal sales. Only five percent of their revenue is generated by eco-tourism. Few of these ranches would be able to survive on ecotourism alone, because of rivalry from better-situated, more attractive destinations.

Fluffy toys

The giraffe proposal was made by the Central African Republic, Chad, Kenya, Mali, Niger and Senegal, over the objections of the 16 countries of SADC.

Animal rights groups vigorously lobbied for the proposal, going so far as distributing fluffy giraffe toys to delegates at CITES and recruiting celebrities with no expertise in wildlife conservation, like Leonardo DiCaprio and Dolly Parton, to their cause.

This makes a mockery of the very serious intersection of conservation with the lives and livelihoods of local communities in Africa.

The emotional manipulation by animal rights NGOs serves to advance the agenda of eliminating not only hunting, but any use of or trade in wild animals. The animal rights agenda stands in direct conflict with the national right of sustainable use conferred by the Convention on Biodiversity.

That the SADC countries, which play host to a majority of the world’s giraffe numbers, could be so easily overruled also violates the CITES principle: that member states should be the best protectors of their own wild fauna and flora.

The danger is that if an entire species (or four) can be listed even if only a few sub-species or geographically distinct populations are under threat, animal rights lobbies – with their vast financial resources and undue influence upon CITES members – will use this tactic to go after many more game species.

Perverse outcome

Spurious trade prohibitions justified only by localised conservation failures elsewhere would have a grave financial impact on the private ranches and game farms that have proven so beneficial to game conservation in southern Africa.

This would have the perverse outcome of harming both wild animal conservation and the welfare of local communities.

The consequence of financial failure is that land now under game and creating decent employment would be converted to livestock or crop farming, which is damaging to conservation and has been proven to create fewer, worse-paying jobs.

CITES must strongly resist influence by external animal rights lobby groups, who serve only their own donor bases. It should endorse wildlife management at a population level instead of at a species level. It ought to respect the sovereignty of major range states over the use and conservation of their own species.

It does none of these things. This will prove to be counter-productive to the conservation objectives of CITES, and it will drive range states to repudiate membership of a Convention in which they are not heard and their interests are ignored.

Disclosure: This article was written in collaboration with Eugène Lapointe, Secretary-General of CITES from 1982 to 1990, and president of the IWMC World Conservation Trust.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.