This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

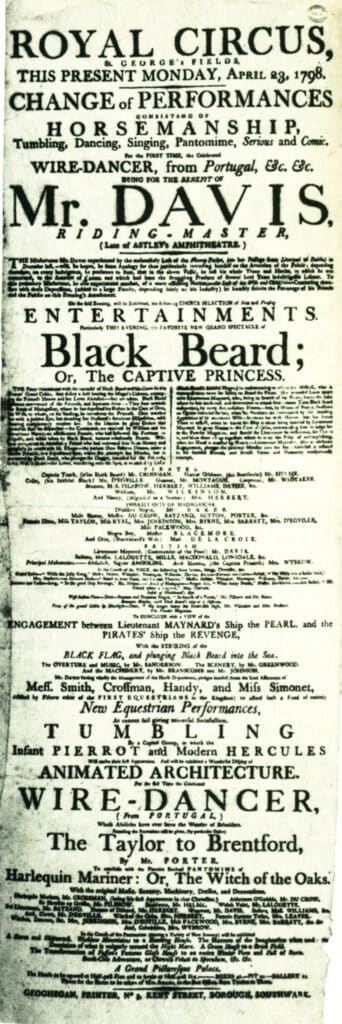

22nd November 1718 – Royal Navy Lieutenant Robert Maynard attacks and boards the vessels of the British pirate Edward Teach (best known as ‘Blackbeard’) off the coast of North Carolina. Maynard’s first officer, Mister Hyde, and Teach himself are among those who die in the fighting

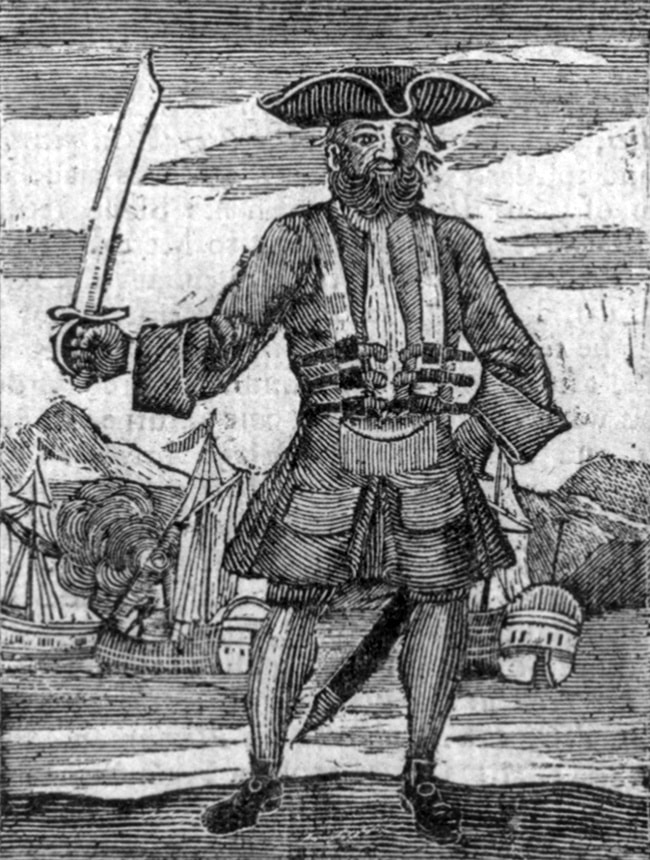

When one thinks of pirates and the Golden Age of Piracy (1650s-1730s), few figures loom as large or are as iconic as Edward Teach, better known as Blackbeard.

Even into the modern period, the appearance and name of Blackbeard dominate our perceptions of piracy, and he regularly appears as a character in pop culture.

A fairly recent notable example would be the 2011 film Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides, in which a fictional version of Blackbeard is the main antagonist.

The film grossed over $1 billion and currently holds the record for the most expensive film ever made.

To tell the story of Blackbeard, however, we must first tell the story of piracy during the later years of its golden age.

Between 1650 and the 1730s, Europe was torn apart by a series of major conflicts between its great powers, such as the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1715). The major naval powers of England, the Netherlands, Spain and France were all involved in the conflict which therefore took on an international character, with the navies and colonies of these nations engaging in battle across the world.

A common practice in warfare at this time was the use of privateers. These were ship’s captains who were given ‘letters of marque’ in terms of which they were essentially given permission to act as pirates on behalf of the country which gave them the letter, and target its enemy shipping.

While this piracy was carried out across the world, the locus was in the busy shipping lanes which passed through the Caribbean or the east coast of the future United States, where British, French, Dutch and Spanish ships carried goods to and from Europe.

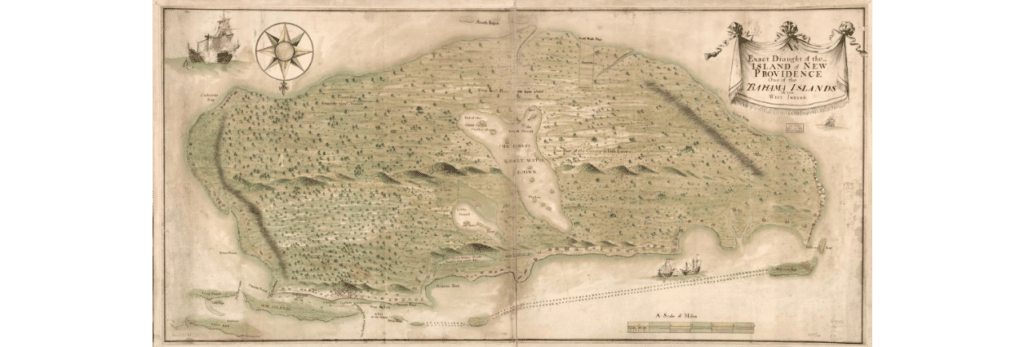

The British Caribbean island colony of New Providence was attacked by a Spanish and French fleet in 1703 and in 1706. This caused the island’s population to abandon it. It was soon reoccupied by English privateers, who quickly established the island as more of a lawless pirate haven than a privateer’s base, and soon the island was considered essentially an independent pirate republic.

As the conflicts in Europe began to wind down, the large number of privateers suddenly found themselves unemployed, but still very much keen on continuing their piracy. This drew more and more former privateers to New Providence.

One of these was a man named Edward Teach.

Teach was born in Bristol in England around the year 1680. While much is speculated about his upbringing, there is little definitive evidence. At some point, likely when he was a young man, Teach travelled to Jamaica, where he became a sailor on privateer ships and, according to some sources, distinguished himself as brave and cunning.

By the time of the end of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1715, Teach had moved to New Providence, and had become a full-on pirate, attacking ships regardless of their national origin.

In 1716 he was given control of a sloop and became a captain in his own right, attacking shipping all around New Providence.

Teach was said to be a large man who wore a large black beard (from which he got his nickname), braided into pigtails and tied with coloured ribbons. He reportedly wore mostly dark clothing, except for a cloak of brightly coloured cloth. He wore on his chest ‘three brace of pistols, hanging in holsters like bandoliers’ and ‘stuck lighted slow matches under his hat’. This was likely calculated to make himself appear bizarre and insane so as to frighten the crews of ships he attacked into surrendering.

By 1717 Teach had amassed a fleet of three ships and was quickly establishing a name for himself as a terrifying and dangerous pirate lord.

In response to the rampant piracy, the British crown increased the anti-piracy operations of the Royal Navy, and on 5 September 1717 issued a pardon to all pirates who surrendered to British authorities. Those who refused the pardon would have bounties placed on their heads. The pardon immediately divided the pirates on New Providence, as many wished to take it. But others, especially those who were Jacobites – opposed to the British Monarchy – sought to keep pirating.

Blackbeard would only hear of the pardon in December of 1717 and decided to reject it. In May of 1718 he had taken his fleet to blockade the settlement of Charles Town in South Carolina and attack all ships which tried to enter the port. When a second pardon was offered by the governor of South Carolina, Blackbeard would again reject it – though half of his crew, of around 600 by this time, would abandon him to seek the pardon.

Soon after Teach changed his mind, too, and decided he would take the pardon by surrendering to the governor of North Carolina, who he believed he could trust. He sent former pirate captain and currently a guest of Blackbeard’s Stede Bonnet to see if the pardon was a trap.

While Bonnet and some of the remaining crew were sailing to seek the pardon, Blackbeard gathered all of the loot onto one of his smaller ships, beached and burned the others and marooned much of his remaining crew so as to secure a greater share of the spoils for himself. He then sailed to Bath in North Carolina and took the pardon there. He settled in the area and for a short time pretended to become a local member of the plantation-owning high society.

This didn’t last long and by August of that year, he returned to piracy, capturing a French ship and claiming it was abandoned. A rigged tribunal found in his favour and ruled the ship salvage. The governor of Pennsylvania, worried by Blackbeard’s obvious continuing piracy, issued a warrant of arrest for Teach.

Two ships set out from Pennsylvania to try to capture him, but ultimately failed.

The governor of Virginia did not trust the North Carolina authorities to deal with Teach and so dispatched his own pirate hunter to track down Blackbeard and bring him back, dead or alive.

Lieutenant Robert Maynard, who would be given command of two sloops, would set out on 17 November 1718 to capture Blackbeard.

A few days later, on 22 November, after scouting out Blackbeard’s position for a time, the pirate hunters struck.

Initially Blackbeard was successful in using his larger number of cannons to drive off one of the sloops. But Maynard had laid a trap for him, having ordered most of his men below decks in the hope that Blackbeard would board his ship, thinking the crew had all been killed.

Blackbeard fell for the ruse; he and his crew leapt aboard Maynard’s ship, thinking it almost empty. But at that moment, the crew burst forth and attacked Blackbeard’s smaller crew.

Teach was killed in the fighting, and his crew eventually surrendered.

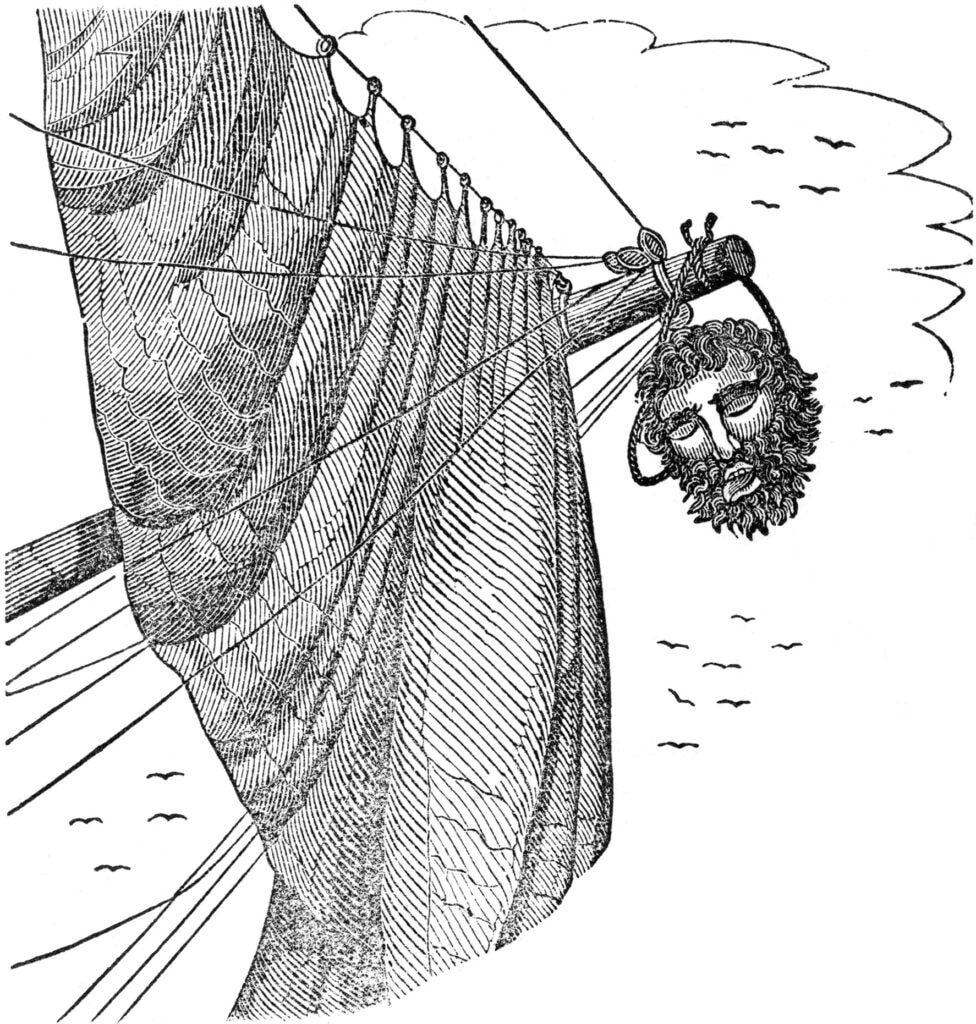

When Teach’s body was examined after the battle it was found he had been shot five times and sustained some 20 cuts. His head was cut off and displayed in the rigging, while his body was tossed overboard.

So ended the short but eventful career of one of history’s most infamous pirates.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend