This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

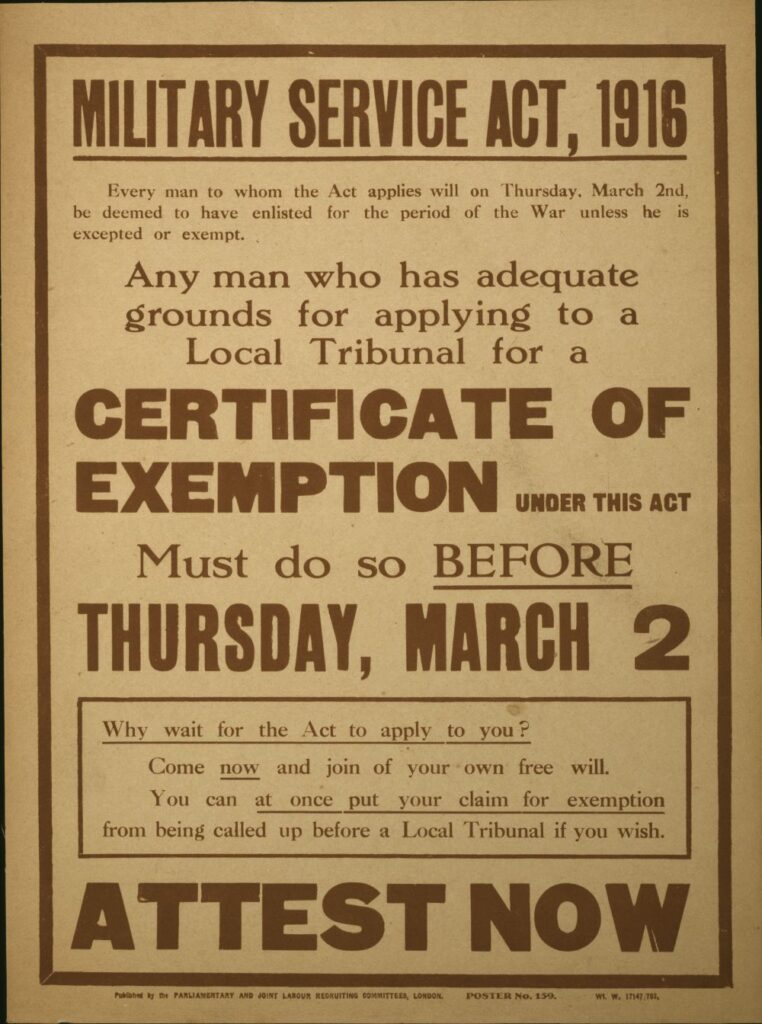

27th January 1916 – World War I: The British government passes the Military Service Act that introduces conscription in the United Kingdom

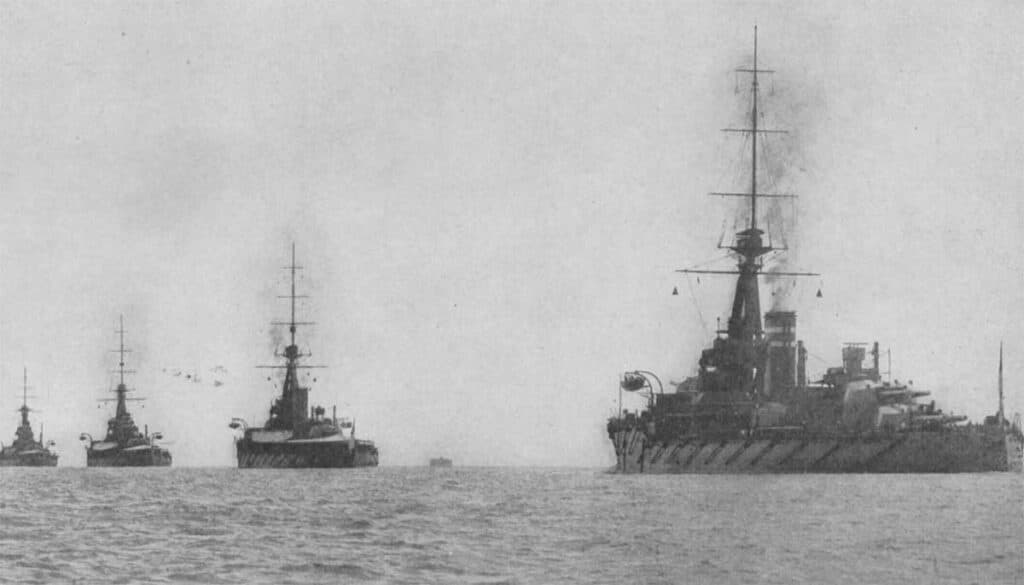

At the outbreak of the First World War, the British Empire relied extremely heavily on its navy for its national defence and maintenance of its empire. The army had been troubled for decades, with the Crimean War in the 1850s and the Second Anglo-Boer War straddling the turn of the century being examples of poor performance for the British army. In both cases the British won, but only through the enormous advantages that their powerful economy and vast navy gave them.

As a result, at the time of the outbreak of the First World War, the British had focused on maintaining a small wholly professional force which would be able to intervene in colonial and great power conflicts in a limited but hopefully decisive way, while the navy projected the majority of British power.

This resulted in an army of 710 000 men, including reserves, of which around 80 000 were regular troops ready for war. In contrast, the French, German and Austrian armies were massive forces, able to deploy hundreds of thousands of conscripted troops to the front by using complex mobilisation systems. The French could field around 4 million troops, the Germans 4.5 million and the Austrians 3 million. The British army was high quality, but incredibly small.

In the opening months of the First World War, during the so called ‘Battle of the Frontiers’ between 7 August and 6 September 1914, the German army with 68 divisions faced an allied force of six British divisions, six Belgian divisions and 62 French divisions.

Entirely unprepared for a major land war in Europe, the British quickly had to enlarge the size of their forces, and reverse the appalling losses experienced in the first months of the war.

These were among the bloodiest in human history. Both sides believed the war would be fought as one of manoeuvre, where aggressive movements by large forces would destroy the enemy. Advances in artillery and the machine gun made this type of warfare immensely costly in human lives and the first months of the war were some of the worst in terms of casualties ever recorded.

Generals quickly found that digging massive trench systems was the only way to protect your troops from modern weapons. As few technologies and tactics existed for breaking these trench systems, stalemate soon set in.

For the first part of the war, the British tried to fill the demands of trench warfare with volunteers.

While conscription was the norm on the continent, the small size of the British army and the protection offered by the British navy meant the British government had never had to engage in large-scale mobilisation and as such conscription was never normalised.

As a result of this, and Britain’s strong liberal tradition, there was significant resistance to the enactment of conscription.

Instead, in 1914 and 1915 the British army relied entirely on volunteers, many of whom were from so-called ‘pals battalions’ groups of men from the same town, factory or football club who were formed together into army units.

Joining up as a group activity with your friends proved highly successful at first and by September 1914 around 500 000 men had already volunteered.

However, as the war dragged on and expanded across the world, the British needed more and more troops to replace the fallen and to fill the new fronts, such as in the Middle East.

While many continued to volunteer, the numbers were just not high enough to meet the army’s needs.

By 1915, the British government realised that it had no choice but to begin conscription. This was controversial, and an issue that would split the Liberal Party in two.

On 27 January 1916, the Military Service Act was passed, requiring all unmarried men between the ages of 18 and 41 to make themselves available for service should they be called up by the government. This did not apply to Ireland, where the government feared the results of imposing conscription on a rebellious population. The only people exempt were clergy, widowed men with children, those doing work deemed important to the nation and those who did not meet the physical requirements. Married men were added to the conscription pool in May of 1916.

By the war’s end in November of 1918, the British Isles would suffer 744 000 dead with many thousands more casualties from the colonies and dominions.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend