A special cabinet meeting on Wednesday discussed slowing down the decommissioning of old coal-fired power stations. It’s one of the smarter ideas we’ve seen in recent months.

When you’re critically short of electricity supply – so much so that you need rolling blackouts for up to ten hours per day – it is sheer lunacy to be talking of decommissioning functioning power stations.

The Integrated Resource Plan of 2019 projects progressive decommissioning of up to 35GW worth of coal-fired power stations by 2050, with more than 10GW of that due by 2030, and 6GW due by 2023.

In reality, Eskom currently uses only just over half of its installed generation capacity of 48GW. This has mired South Africa into persistently high stages of load-shedding, which together with load curtailment (which rations electricity to large industrial users) has meant Eskom couldn’t supply up to 8GW of electricity demand, which lately has been hovering north of 32GW.

This is the context in which we must consider the proposed decommissioning of coal-fired power stations, which had been planned in less gloomy days to make way for renewable energy alternatives.

Slow down

On Wednesday, President Cyril Ramaphosa called a special Cabinet meeting to discuss a plan by electricity minister Kgosientsho Ramokgopa to slow down the phase-out of coal-fired power stations.

Some commentators were quick out of the blocks with objections. Delaying the shuttering of coal-fired plants would, according to some critics, jeopardise the $8.5 billion in bribes offered by the so-called Just Energy Transition Partnership, consisting of Germany, France, the UK, the US and the EU, to convince South Africa’s leaders to act against its own best interests and rapidly move away from coal in favour of solar and wind energy.

At least the German embassy realised that making a scene over a slower transition would be rather hypocritical, telling News24 that concrete dates for decommissioning coal-fired power plants are for South Africa to decide, based on technical and energy security requirements.

‘Germany itself has been forced to temporarily postpone the decommissioning of some of its coal-based power generation in order to safeguard energy security,’ unnamed embassy sources reportedly said.

The article also highlights estimated deaths from air pollution caused by Eskom’s coal-fired power stations, based on a report produced by the Helsinki-based Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREC).

The CREC couldn’t find enough problems to solve in wealthy, capitalist Finland, so it decided to poke its nose into our business.

It also told us that plans to temporarily exempt Kusile from full flue-gas scrubbing rules to enable it to bring three damaged units online sooner might – they estimate wildly – kill 680 people by diseases caused by pollution.

Pollution

Of course, the air pollution of coal-fired power stations is no joke. But neither is indoor air pollution.

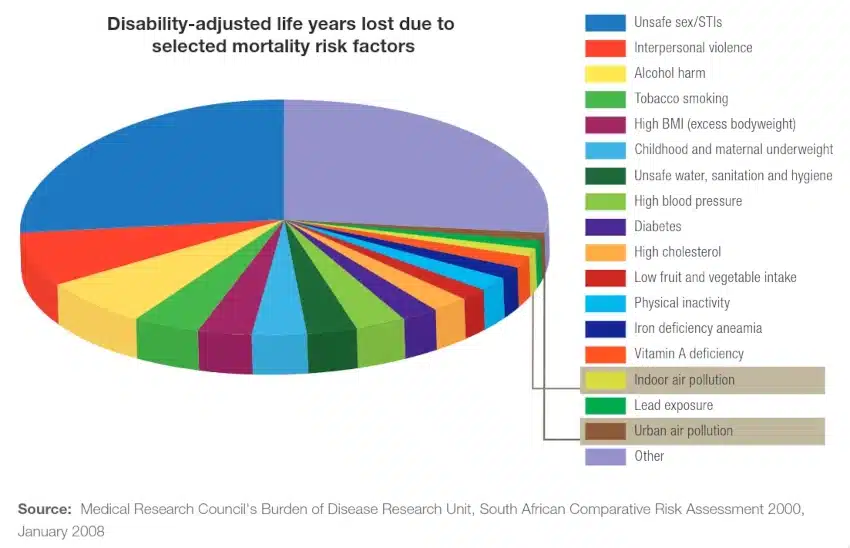

Far more South Africans are exposed to indoor air pollution than to outdoor air pollution. Pollution levels caused by wood- or coal-fed cooking and heating fires in rural and township kitchens can be a thousand times worse than national air quality standards.

What the meddling Fins failed to account for, was the fact that load-shedding significantly increases the risk of respiratory disease, acute toxicity, or fires caused by millions of people turning to indoor fires for cooking and heating. Individual cases are rarely reported, but they’re horrific. Globally, deaths due to indoor air pollution exceed deaths caused by outdoor air pollution.

What both articles also fail to point out is that air pollution, whether indoors or outdoors, is only a very small contributor to the disability-adjusted life years lost for South Africans:

Poverty is another major cause of reduced life quality and premature death. Inasmuch as load-shedding causes unemployment, business closures, lost revenues and lower economic growth, it causes poverty.

Cherry-picking

So, the environmentalists, unsurprisingly, are cherry-picking data to point out only the negative effects of keeping coal-fired power plants running, without pointing out the positive results of having sufficient electricity available to increase living standards and offer people a safer, healthier substitute to burning carbon-based fuels right in their homes.

One could go further, and argue that the pressure upon South Africa to rush into a renewable energy future itself runs contrary to the country’s best interests.

Environmental activists are fond of pointing out that the price of solar and wind is now less than the cost of gas, coal or nuclear energy. But that is only true if you’re very selective about how you calculate your costs.

Solar and wind might be cheap at the gate, but that gate is typically very far from where the power is needed. Because individual solar or wind farms are very small (on the order of 100MW), a massive amount of transmission infrastructure is required to connect them to the grid.

Additionally, because solar and wind are not reliable, and cannot be turned on and off to match demand, they either require massive grid storage capacity, which is expensive and technically difficult, or they require backup in the form of fossil-fuel-fired power stations. Both of these make renewable energy far more expensive than the price tag first appears.

Expensive

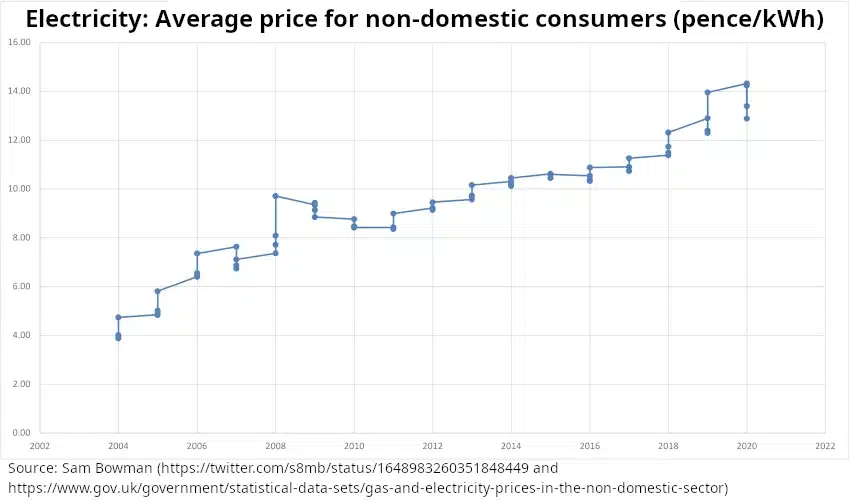

In the UK, which has bet big on renewables, the price of electricity for non-domestic use (which unlike domestic power bills has not been subsidised) tripled in nominal terms, and more than doubled in real terms, in the last 20 years.

In general, the more countries or states rely on grid-scale renewable energy, the more expensive their electricity becomes. Germany’s vaunted Energiewende (and its hare-brained abandonment of nuclear energy) has made its electricity the most expensive in Europe. Denmark, which gets more than half of its energy from wind, is a close second. By contrast, countries that rely more heavily on coal, natural gas, nuclear or hydro-power have electricity prices well below average.

Given the dire state of South Africa’s electricity infrastructure, we cannot afford anything that will make electricity more expensive than it absolutely needs to be, and cannot afford anything that will in any way curtail the amount of available electricity.

Let the rich countries, who became rich on the back of fossil fuels, worry about their own continued reliance on coal whenever it suits them, and let countries like South Africa use the best mix it can come up with, no matter what the source.

Immoral

I would love to see a future without coal. I would love to see a future that relied heavily on clean, abundant nuclear energy. I am sceptical that so-called renewables will ever out-compete nuclear, gas or coal, in real terms, but if they do, good for them. Private suppliers are free to compete to deliver reliable electricity at the lowest prices possible. How they do so doesn’t matter to me.

Residential and commercial solar also makes a lot of sense, provided you are a property owner. It doesn’t work for renters, or for the vast majority of South Africans whose entire houses cost less than a half-decent solar installation.

At grid scale, to artificially restrict South Africa’s electricity generation in ways that could raise the price of electricity, raise the costs to Eskom, or raise the risk of load-shedding, is not just unreasonable; it is immoral.

Let us count the cost of inadequate electricity supply, the cost of indoor air pollution, the cost of deindustrialisation, and the cost of poverty and unemployment, before we bow to the environmental whims of the urban elites at home and the neo-colonialists of the rich world hoping to suborn poor countries to clean up the supposed environmental mess the rich countries made in the first place.

Future-proof

The world’s climate goals – even if we assume they are both reasonable and necessary, which they aren’t – do not depend to any great extent on South Africa.

Let us first generate enough electricity to re-ignite economic growth, and to build a prudent reserve to cope with fluctuations in demand and unplanned maintenance, before we start thinking of luxuries that please Finnish activists such as decarbonising our electricity mix.

Only then can we future-proof our electricity sector, ideally by investing in new nuclear technology, rather than spoiling the countryside with windmills and solar farms and thousands of kilometres of new transmission pylons.

Credit

There was a time when one could give substantial credit to the ANC for rolling out water and electricity infrastructure to the townships and rural areas that the apartheid regime so cruelly neglected.

Those days are long gone, sadly. Nowadays, one can rarely give the ANC credit for anything, especially not when it comes to electricity.

In this case, however, we must give credit where it is due. In the face of crippling electricity shortages, Ramokgopa and Ramaphosa are quite right to be reluctant to decommission working power stations. Run them for as long as they remain economically viable.

[Image: Ralf Vetterle from Pixabay]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend